Service Sharing: How Counties Do More with Less

What is Service Sharing?

Intergovernmental service sharing occurs when two or more local government entities cooperate to provide a single service or set of services to residents. Sometimes, one local government entity will provide a service to another for sale through a contract, on a fee-for-service basis or for free. Other times, two or more entities will work together to provide a service jointly. Service sharing agreements can range from formal written contracts or detailed memoranda of understanding to informal understandings of cooperation based on a simple handshake. Local government entities can also partner with the corporate and nonprofit sectors to increase efficiency through public-private partnerships.1

Printable PDF Share on TwitterIntroduction

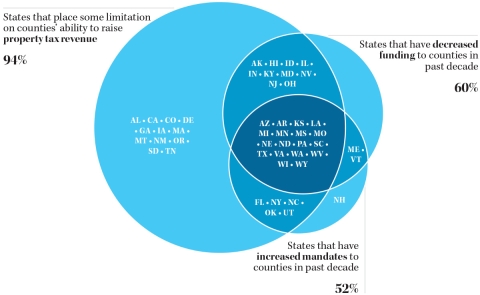

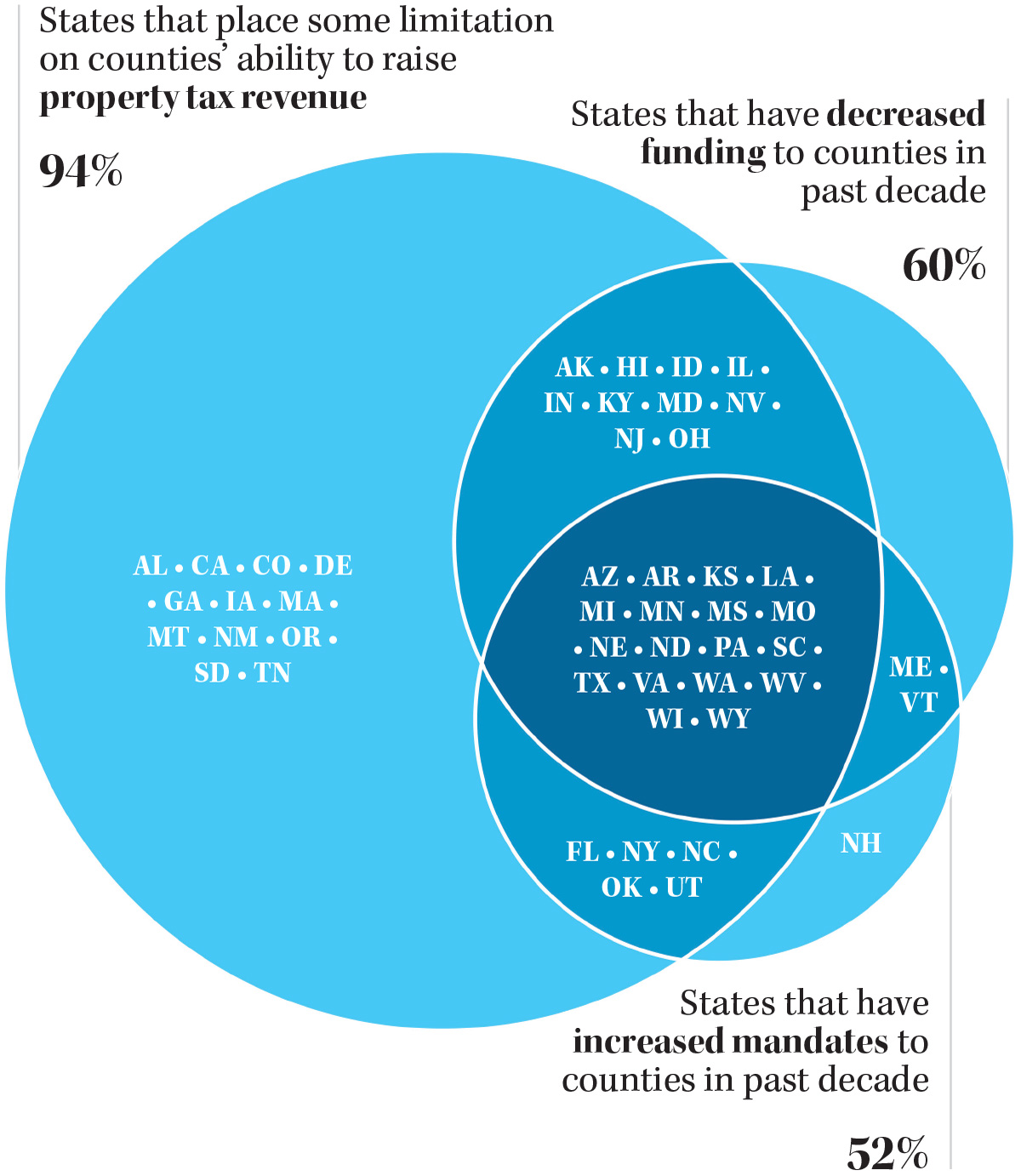

The current financial environment compels county governments to be innovative and do more with less. Counties are caught between state policies that restrict or diminish their ability to raise revenue and ones that increase the number and scope of services they must provide. Nearly three-quarters (73 percent) of states have increased the number or scope of mandated services to counties, decreased state funding for counties or implemented a combination of both over the past decade.2 Moreover, 45 states place some limitation on the ability of counties to raise property tax revenue â the main general revenue source for most counties.3 (See Figure 1). When the Great Recession hit in 2008, counties found themselves under new pressure to increase efficiency, for nearly half of counties (46 percent) in 2013 had not yet seen their general revenues recover to 2007 levels.4

In the face of these financial challenges, many counties work with their citizens and other governments to raise funds locally, and they collaborate with other entities to gain efficiencies through service sharing. Service sharing agreements are an invaluable method for counties to increase efficiency. Rather than cut services when faced with budgetary strain, county governments partner with cities, other counties, special taxing districts, school districts, private corporations, nonprofits or other entities to share the burden of service provision. Different departments within a single county can also engage in service sharing.

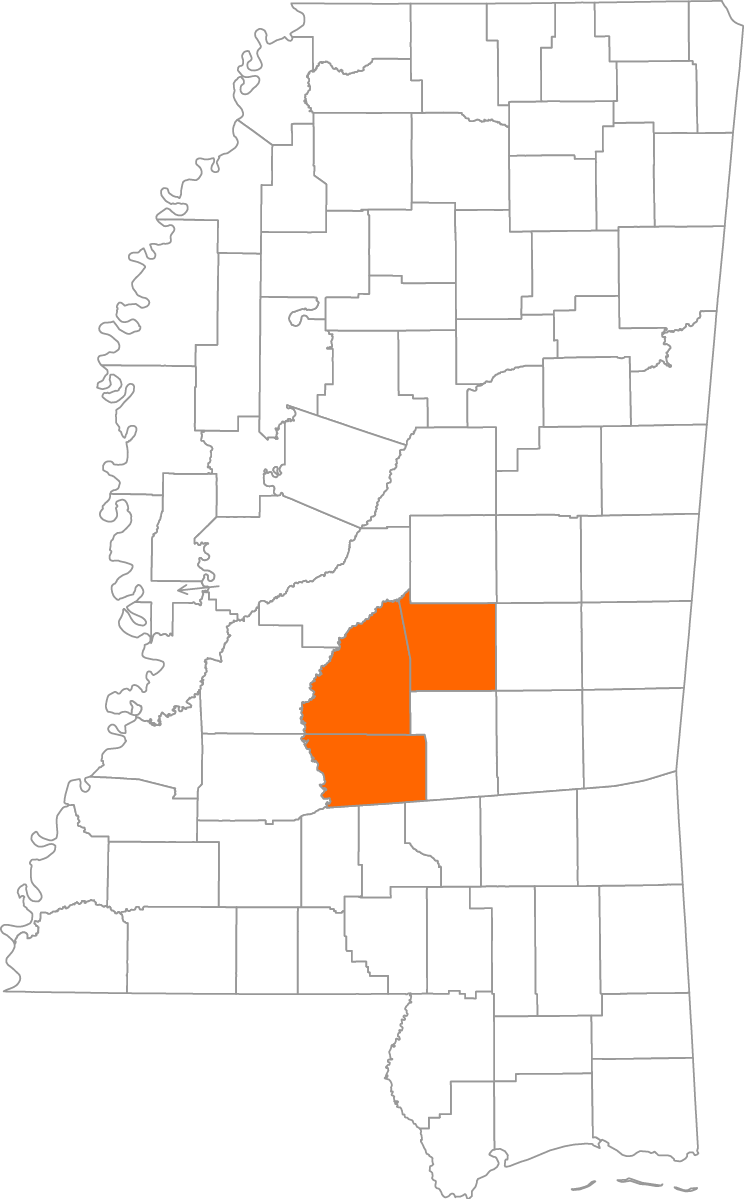

By examining three examples of service sharing that occurred in the wake of the latest economic downturn, this brief shows different ways in which counties, in an environment of fiscal constraints, can continue providing their residents with quality services by cooperating with other entities. This brief is the result of various interviews conducted with county officials and staff from Marion County (Ohio), Rankin County (Miss.) and Erie County (N.Y.).

Despite fiscal constraints, counties can continue providing their residents w/ quality services by cooperating w/ other entities.

Five Characteristics of a Successful Service Sharing Initiative

- Create a team of county and local government leaders to guide the service sharing initiative and manage communication between parties.

- Trust that your local government partner(s) desire the same end goals as you and clearly communicate them. Evaluate and use each otherâs strengths.

- Be flexible and willing to alter and improve the agreement over time. Test different ideas along the way with pilot projects.

- Develop methods to measure whether the shared service is fulfilling its goals. Establish easily-achievable short-term goals along the way to improve morale.

- Clearly document the responsibilities of all parties involved and make sure these responsibilities are understood. Provide an easy way to opt out of the shared service, recognizing that local government needs change over time.

Source: Eric Zeemering and Daryl Delabbio, âA County Managerâs Guide to Shared Services in Local Government,â IBM Center for the Business of Government, Collaborating Across Boundaries Series, 2013.

Figure 1: The Environment of Fiscal Constraints for Counties

Share of states

Note: Figure includes only the 48 states with county governments. Conn. and R.I. have no county governments and were excluded from the analysis

Source: Griffith, Harris and Istrate, Doing More with Less, NACo, 2016

Collabor8 Virtual Call Center

Carroll, Delaware, Hancock, Holmes, Knox, Marion, Morrow, Sandusky and Wood Counties, Ohio

| Carroll County | 27,669 |

| Delaware County | 196,463 |

| Hancock County | 75,872 |

| Holmes County | 43,936 |

| Knox County | 60,814 |

| Marion County | 65,096 |

| Morrow County | 35,036 |

| Sandusky County | 59,330 |

| Wood County | 130,219 |

| Carroll County | 5.7% |

| Delaware County | 3.1% |

| Hancock County | 3% |

| Holmes County | 3% |

| Knox County | 4.2% |

| Marion County | 3.9% |

| Morrow County | 3.8% |

| Sandusky County | 3.6% |

| Wood County | 3.4% |

| Carroll County | $0.76 billion |

| Delaware County | $10.73 billion |

| Hancock County | $4.46 billion |

| Holmes County | $2.05 billion |

| Knox County | $2.07 billion |

| Marion County | $2.23 billion |

| Morrow County | $0.55 billion |

| Sandusky County | $2.29 billion |

| Wood County | $6.14 billion |

| Carroll County | $18,378 |

| Delaware County | $33,701 |

| Hancock County | $36,388 |

| Holmes County | $21,241 |

| Knox County | $26,623 |

| Marion County | $29,878 |

| Morrow County | $18,446 |

| Sandusky County | $30,324 |

| Wood County | $34,154 |

Source: NACo County Explorer, 2017.

Context: class="inline-header">Prior to 2011, each county in Ohio administered human services delivery separately to residents who used these public assistance services (i.e., Medicaid, cash assistance and food assistance). In the wake of the latest recession, state funding to counties decreased despite a growing population and demand for services. The lack of funding diminished county staff levels, and the remaining county employees struggled as caseloads increased, ultimately causing delays in response times to needy families. It soon became clear to Ohioâs counties that their model for human service delivery was no longer sustainable.

Solution: class="inline-header">In June of 2011, the human services agencies of seven Ohio counties (Delaware, Hancock, Knox, Marion, Morrow, Sandusky and Wood) worked with Ohioâs Department of Job and Family Services (ODJFS) to find a solution. Through a memorandum of understanding, the counties formed a common 1-800 number that connects the agencies and allows the counties to share staff and resources. Traditionally, each county would assign cases or customers to their county case managers, and the employees saw the cases through from beginning to end. Now, however, the call center distributes calls to any case manager in any county â to whomever is available to perform the specific task needed. Case managers thus work on a variety of cases throughout the day on an as-needed basis, and residents do not need to wait to hear back from one specific employee. Through an in-depth operations manual, the counties have standardized their once-unique processes to provide uniform quality services to residents.

The virtual call center was established using funding from both ODJFS and the seven initial counties. OJDFS supplied funding to cover the infrastructure costs of the virtual call center (approximately $1.2 million), and the seven counties covered the costs of professional services to unify the seven county systems, the costs of toll-free call charges and the costs of technology maintenance (approximately $711,000). To divide the startup costs evenly, the seven participating counties agreed to a cost sharing formula based on the prorated amount of the stateâs allocation formula for county funding of Medicaid, Food Assistance and TANF programs. Now, Collabor8âs nine counties divide current funding costs using the same formula and pay for these costs out of their general funds.

Since its inception in 2011, Collabor8 has reduced the wait time for residents and increased productivity for all counties involved. None of the original seven counties have dropped out of the agreement; instead, two more Ohio counties â Holmes and Carroll â have joined the call center. Begun as a pilot project, the call center has become so successful that the state of Ohio is replicating this program across the state, forming groups of eight to ten counties to operate other shared call centers.

âBe bold and think broadly about new solutions...be flexible and open to change along the wayâ

â Roxane Somerlot, Director of Jobs and Family Services, Marion County, Ohio

Challenges: class="inline-header">Residents quickly adapted to Collabor8âs new method of case management; however, staff turnover initially increased, since many found it difficult to adjust to a call center environment after previously working face-to-face with customers. Collabor8 met this challenge by recruiting staff from another nearby call center that recently downsized. For any county wishing to replicate this model, staff training is an essential component, requiring leniency from staff and supervisors alike throughout the transition. Ms. Somerlot recommended other counties facing similar challenges to be bold and think broadly about new solutions, to be flexible and open to change along the way and to be patient with staff during the transition.

| Rankin County | 150,228 |

| Scott County | 28,207 |

| Simpson County | 26,912 |

| Rankin County | 3.8% |

| Scott County | 4.1% |

| Simpson County | 4.9% |

| Rankin County | $5.64 billion |

| Scott County | $0.94 billion |

| Simpson County | $0.57 billion |

| Rankin County | $29,000 |

| Scott County | $26,217 |

| Simpson County | $20,465 |

Source: NACo County Explorer, 2017.

âLook at your technology, look at where youâre heading and think of the future. Then, talk to your neighbors and see where they are, too.â

â Bob Wedgeworth, Director of Emergency Communications, Rankin County, Mass.

âLook at your technology, look at where youâre heading and think of the future. Then, talk to your neighbors and see where they are, too.â

â Bob Wedgeworth, Director of Emergency Communications, Rankin County, Mass.

Context: class="inline-header"> Funding for Mississippi countiesâ 911 operations comes from a quickly depleting revenue source: landline fees. Landline fee revenues have been steadily decreasing for years, while the number of 911 calls has been increasing due to population growth. In 2003, fewer than 5 percent of adults in the U.S. had only wireless telephone service; by 2015, that number was over 47 percent.5 (See Figure 2). According to a 2016 report from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), Mississippi is the only state aside from Wisconsin that does not have a wireless fee to fund 911 systems.6 Mississippi counties have pushed for cell phone fees, but that change has not yet made it through the state legislature, leaving counties to face growing 911 costs with a declining revenue source.

Figure 2: Wireless Telephone Usage, 2003-2015

Percent of adults in the U.S. with only wireless telephone service

National Health Interview Statistics, Wireless Substitutions: Early Release of Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, July-December 2015 (2016)

National Health Interview Statistics, Wireless Substitutions: Early Release of Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, July-December 2015 (2016)

Solution: class="inline-header">When Rankin County, faced with the same funding problems as other Mississippi counties, decided its 911 system was outdated in 2013, the county looked for an innovative solution. Rather than perform a bare bones upgrade to minimize expenses, Rankin County looked to its neighbors, Scott and Simpson counties, which were also in need of upgrades to their 911 systems. Since the cost for the upgraded system did not depend on the number of calls coming through, the cooperation of the three counties made financial sense. Rankin County upgraded its system to the best available technology, paying for the upgrade itself, and by the following year, both Scott and Simpson counties were rerouting their 911 calls through Rankin Countyâs system. Now, all three counties have access to Next Generation 911 (NG911) â a technology none of the counties could have afforded on their own â and Scott and Simpson counties each contribute funding for operations in accordance with their population levels. Among other benefits, NG911 allows the public to send texts and pictures to the public safety answering point (PSAP), and it allows emergency workers to identify the location of the callerâs wireless phone, improving response time.7 The system has functioned well ever since the upgrade and partnership began, and the counties have enjoyed the full support of the public.

Upgrading Rankin Co., Miss. 911 technology was a success, in part by sharing costs with its neighbors

Challenges: class="inline-header">The majority of Mississippiâs counties are small, rural counties. Only 14 of Mississippiâs 82 counties have more than 50,000 residents, per 2016 U.S. Census Bureau data. Scott and Simpson counties each have fewer than 30,000 residents. Upgrading a 911 system is simply not feasible for many small county budgets, as even basic maintenance costs for a PSAP can stretch small counties. For this reason, the state of Mississippi has begun to roll out its own plan for regionalizing 911 services, using Rankin, Scott and Simpson counties as a model. For any county wishing to replicate this model, Bob Wedgeworth gave this advice: âLook at your technology, look at where you are heading and think of the future. Then, talk to your neighbors and see where they are, too.â

Source: NACo County Explorer, 2017.

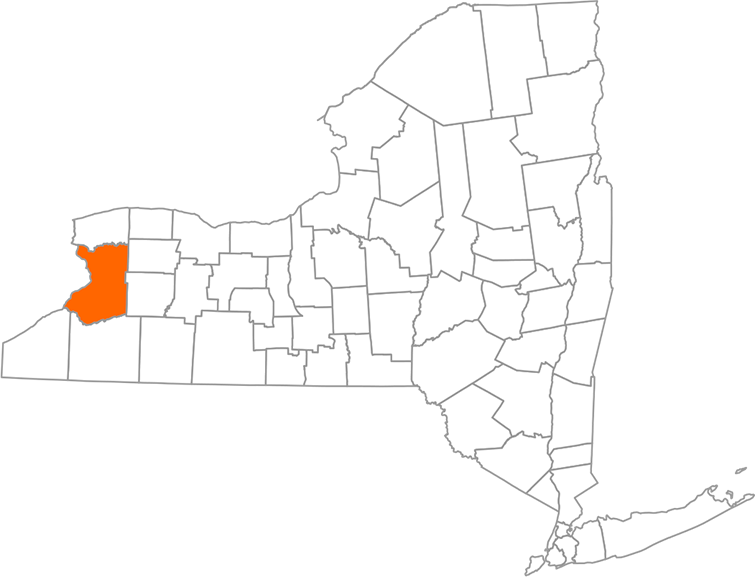

Context: class="inline-header">Erie County, N.Y., like much of upstate New York, has been suffering from deindustrialization for over half a century. Since 1950, the countyâs population has only increased by 2 percent, and the city of Buffalo (the county seat) has lost 55 percent of its population, resulting in an oversupply of housing.8 Coupled with the financial and housing crises of 2008, Erie County wound up with over 36,000 vacant properties throughout the county in 2010 â 20,000 of which were in Buffalo â as well as nearly 60,000 tax liens on properties.9 A vacant property causes houses within 150 feet to lose over $7,000 in property value and is likely to result in a 15 percent increase in crime within 250 feet of the property â a percentage that only increases the longer the property remains vacant.10 (See Figure 3). The increased public safety costs, as well as the lost property taxes and assessed property value, can create additional fiscal stress for a county budget already faced with increasing state mandates and other decreasing revenue streams.

Figure 3: The Effects of Vacant Properties

Hover over the circles to interact with Figure 3.

Tap on the circles to interact with Figure 3

A vacant property is likely to result in a 15 percent increase in crime within 250 feet of the property

A vacant property causes houses within 150 feet to lose over $7,000 in property value

Source: New York State Office of the Attorney General, âRevitalizing NY State: A Report on New York Attorney General Eric T. Schneidermanâs Land Bank Community Revitalization Initiative,â November 2016. Refers to a study done in Pittsburgh, Penn.

Solution: class="inline-header">In 2012, Erie County, N.Y. worked with its municipalities to establish a land bank called the âBuffalo-Erie-Niagara Land Improvement Corporationâ (BENLIC). BENLICâs purpose is to rehabilitate or demolish vacant and neglected properties that have a negative effect on surrounding property values, then sell the properties to responsible owners who will help return them to the tax roll. BENLIC clears the taxes and title of newly acquired property to enable its future productive use. Through BENLIC, Erie County and its municipalities determine which abandoned properties will have the most beneficial impact on the community when rehabilitated or demolished. BENLICâs board is comprised of representatives of Erie County, the city of Buffalo, the city of Lackawanna, the city of Tonawanda and the state of N.Y. Although the land bank currently only covers Erie County and its municipalities, BENLICâs inter-municipal agreement allows Niagara County to become a participating member in the future, if the county desires.

In 2011, the governor of New York signed into law the New York State Land Bank Act, which allowed for the creation of up to ten land banks across the state, one of which was BENLIC. This legislation permits land banks to obtain property through the tax foreclosure process. When a property owner fails to pay their taxes, the taxing authority eventually sells the property at an auction. At these auctions, N.Y. land banks can exercise a âpreferred bidâ authority to supersede all other bidders, then they can hold the land tax-free, lease properties and negotiate sales based on community needs. The New York State Office of the Attorney General funds these land banks through a multibillion dollar settlement with lending institutions that played a role in the housing crisis. BENLIC also generates revenue by selling rehabilitated properties.

With these tools in hand, BENLIC has demolished or renovated over 130 unsafe buildings itself to date, replacing these dangerous eyesores with homes that improve neighborhood property values and providing affordable housing for low-income families.11 In 2016 alone, BENLIC acquired nearly 150 tax-foreclosed properties using its preferred bid authority. While some properties were rehabilitated by BENLIC itself, others were given to Buffaloâs Division of Real Estate or sold to investors who will be legally responsible for revitalizing the property.12 By the end of 2017, BENLIC will have helped return more than $5 million in assessed value to local tax rolls, not to mention the other benefits communities receive from reduced crime rates and increased property values.13 (See Figure 4). To achieve these benefits, BENLIC recorded approximately $3.4 million in expenses from 2013 through 2016, as well as an additional $400,000 in proposed 2017 expenses.14

â[The] goal is to foster long-term community and economic development.â

â Jocelyn Gordon, Executive Director of BENLIC, Erie County, N.Y.

BENLIC workers replacing demolished houses with move-in ready homes

Challenges: class="inline-header">BENLIC was established as an inter-municipal agreement between Erie County and its 44 municipalities. Because the need is great and the resources limited, the county must work closely with these municipalities to determine which properties will have the most beneficial impact on the community. The involvement of multiple local government units slows the land bankâs work, since all the local government boards involved must come to a consensus; nevertheless, the countyâs cooperation with its municipalities provides community development benefits that far outweigh the cost.

By sharing services, Erie County land bank helped return $5 million in assessed value to local tax rolls by end of 2017

Funding is another major challenge for BENLIC, and indeed for all N.Y. land banks, since they are not able to earn revenue from every project, especially when working in low-income areas. The funding provided by the N.Y. Attorney General is limited and unsustainable, so BENLIC and the other N.Y. land banks will eventually need to find a recurring source of income to continue operating. In Ohio, the state government solved this problem by redirecting 5 percent of excess penalties and interest from residents who fail to pay their property taxes on time to fund land banks. New York has not yet passed such a law. For counties facing similar issues, land banks are a great tool for sustainable neighborhood development, but they are not an end in themselves: Their goal is to foster long-term community and economic development, as Ms. Jocelyn Gordon explained. With a reliable funding source, a land bank can contribute significantly to a community.

Figure 4: The Success of BENLIC

Source: New York Land Bank Association, âNew York State Land Banks,â April 2017, and New York State Office of the Attorney General, âRevitalizing NY State: A Report on New York Attorney General Eric T. Schneidermanâs Land Bank Community Revitalization Initiative,â November 2016.

Conclusion

Service sharing is by no means a new idea among counties. For decades, counties have been sharing services all over the country. Increasing state and federal mandates, rising state limitations on countiesâ abilities to raise revenues and declining state funding have further compounded this problem. The latest economic downturn made matters worse for many counties around the country, which are still reeling from the effects of the recession. In such an environment of fiscal constraints, finding new ways to share services is an alternative to cutting service provision and a way to continue to provide essential services to the most vulnerable of our residents.

Endnotes

[1] Eric Zeemering and Daryl Delabbio, “A County Manager’s Guide to Shared Services in Local Government,” IBM Center for the Business of Government, Collaborating Across Boundaries Series, 2013.

[2] Joel Griffith, Jonathan Harris and Emilia Istrate, “Doing More with Less: State Revenue Limitations and Mandates on County Finances”, National Association of Counties, NACo Policy Research Paper Series, Issue 5, November 2016.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Emilia Istrate and Daniel Handy, “The State of County Finances: Progress through Adversity,” National Association of Counties, NACo Trends Analysis Paper Series, Issue 7, October 2016

[5] Andrew Hartsig, “Calling 911: Funding and Technological Challenges of County 911 Call Centers,” National Association of Counties, NACo Policy Research Paper Series, Issue 6, February 2017.

[6] Federal Communications Commission, “Eighth Annual Report to Congress: On State Collection and Distribution of 911 and Enhanced 911 Fees and Charges,” December 2016. Wyoming did not respond to the FCC’s survey.

[7] Andrew Hartsig, 2017.

[8] New York Land Bank Association, “New York State Land Banks,” April 2017.

[9] BENLIC Analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, 2010.

[10] New York State Office of the Attorney General, “Revitalizing NY State: A Report on New York Attorney General Eric T. Schneiderman’s Land Bank Community Revitalization Initiative,” November 2016. Refers to a study done in Pittsburgh, Penn.

[11] Ibid.

[12] New York Land Bank Association, 2017.

[13] Ibid.

[14] See BENLIC’s 2013-2016 Financial Statements and BENLIC’s 2017 Adopted Budget.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Roxane Somerlot (Marion County, Ohio), Bob Wedgeworth (Rankin County, Miss.) and Jocelyn Gordon (Erie County, N.Y.) for providing essential information and comments for the study. Without them, this project would not have been possible. Within the National Association of Counties, the author would like to thank Emilia Istrate, Christina Iskandar, Andrew Hartsig, David Jackson, Jack Peterson, Maeghan Gilmore, Sanah Baig and Anna Martin for their helpÂful comments and contributions. The author also expresses his appreciaÂtion to his Public Affairs colleagues for the graphic design and the website of the report.

For more information:

Dr. Emilia Istrate

Managing Director, Counties Futures La

research@naco.org

Jonathan Harris

Research Associate

research@naco.org

About the Counties futures Lab

The NACo Counties Future Lab brings together leading national experts to examine and forecast the trends, innovations and promises of county government with an eye toward positioning Americaâs county leaders for success. Focusing primarily on pressing county governance and management issues â and grounded in analytics, data and knowledge sharing â the Lab delivers research studies, reports and other actionable intelligence to a variety of venues in collaboration with corporate, academic and philanthropic thought leaders to promote the county government of the future.