Managing Disasters at the County-Level: A Focus on Flooding

Upcoming Events

Related News

Introduction

Disasters – whether naturally occurring or man-made,1 foreseeable and unforeseeable – can have a profound impact on counties across the United States. In order to remain healthy, vibrant, safe and economically competitive, America’s counties must be able to anticipate and adapt to a myriad of changing physical, environmental, social and economic conditions. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) closely tracks disaster events across the U.S. that result in losses exceeding $1 billion. In 2016, there were 15 such events – including 4 floods, 8 severe storms, and a tropical cyclone – resulting in the deaths of 138 people.2 NOAA’s data suggests that such severe weather events have also become more frequent: an average of 5.5 disasters occurred annually from 1980-2016, whereas the frequency has almost doubled to 10.6 events annually when looking at just the most recent 5 years alone (2012-2016). Given the increasing regularity and costs of disasters, it has never been more important for counties to take proper steps to protect their people and property from all potential hazards.

Last year, 878 counties were declared major disasters by the federal government,3 resulting in $46 billion in total damage.4 County governments support the operation of nearly 1,000 hospitals and the construction and maintenance of 45 percent of public roads and 40 percent of bridges throughout the United States. Each year counties annually spend almost $83 billion on community health and hospitals, $22 billion on sewage and solid waste management, and $122 billion on building public infrastructure and maintaining and operating public works. In order to protect these investments, counties must develop preventative plans to mitigate risk and determine how to respond if and when a disaster unfolds.

This report focuses on emergency management for flooding, the most common natural hazard. However, the majority of principles highlighted here can be applied to virtually any emergency or disaster situation. County best practices from across the nation are used to underscore and exemplify each resilience strategy. A number of research organizations have also shared practical approaches that counties can utilize to increase their resilience and decrease the impact and cost of disasters. While each of these processes can vary to a certain degree, they all emphasize the need for stakeholder engagement and the development of a comprehensive risk assessment. A robust risk assessment identifies and assesses local infrastructure and the built environment, shocks and stresses, laws and regulations and social service needs within the community. County leaders can use this report to better understand the emergency management cycle and the breadth of resilience strategies available as they work to make their counties more resilient, healthy and safe for residents.

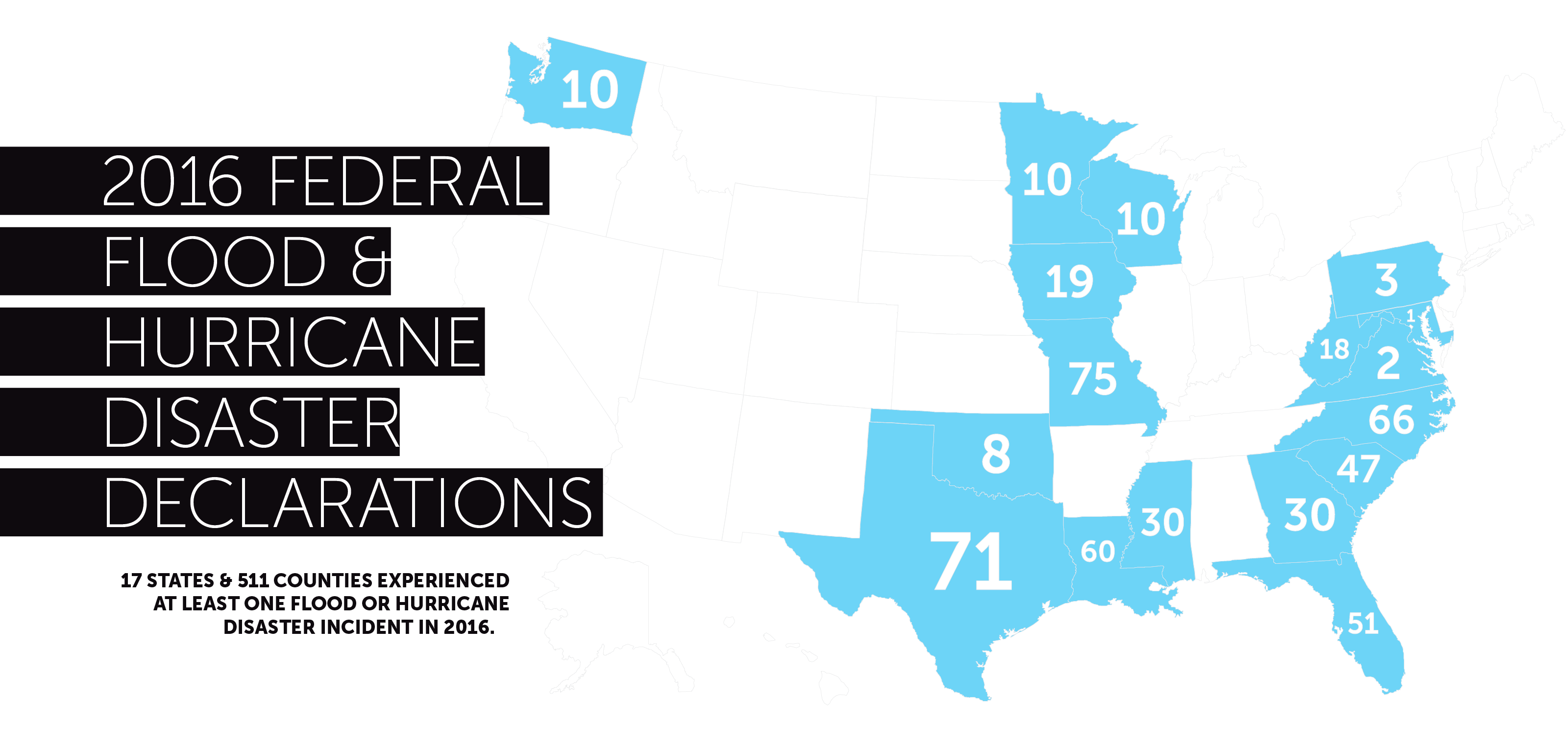

Disaster Declarations

The amount of FEMA assistance a county can receive is reliant upon whether or not the President of the United States declares the situation a federally declared disaster. There are two types of disaster declarations: Emergency Declarations and Major Disaster Declarations. The type of declaration is determined by the size and scope of the disaster. Not all assistance programs are activated for every disaster. Learn more about the disaster declaration process at https://www.fema.gov/disaster-declaration-process.

Types of Disasters

Natural Disasters

- Agricultural diseases & pests

- Damaging Winds

- Drought and water shortage

- Earthquakes

- Emergency diseases (pandemic influenza)

- Extreme heat

- Floods and flash floods

- Hail

- Hurricanes and tropical storms

- Landslides & debris flow

- Thunderstorms and lighting

- Tornadoes

- Tsunamis

- Wildfire

- Winter and ice storms

- Sinkholes

Man-made Disasters

- Hazardous materials

- Power service disruption & blackout

- Nuclear power plant and nuclear blast

- Radiological emergencies

- Chemical threat and biological weapons

- Cyber attacks

- Explosion

- Civil unrest

The Emergency Management Cycle5

The emergency management cycle is a continuous and never-ending process. Various phases can often happen at the same time.

Mitigation

Mitigation is the prevention of future emergencies or the minimization of their effects. It is ongoing work that happens both before and after a hazard event takes place. It is internal to the county and involves the establishment of programs and regulations that aid both the county and its residents in achieving the county’s mitigation goals.

Preparedness

Preparedness occurs all the time but primarily before an event in order to ensure the county is ready to respond to a disaster, crisis or any other type of emergency situation. It is a continuous process requiring plans, procedures and protocols to be regularly evaluated and improved to reflect changes to the county’s physical and organizational environment. It is important to coordinate with local community partners (e.g. the local Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster) and leading national response agencies (e.g. FEMA and the Red Cross) to ensure prompt and comprehensive coverage of county needs during a disaster. The overall goal of preparedness is to minimize the effects of the event on county residents and vital county utilities and facilities.

The Response Phase

The response phase is the shortest, and takes place immediately prior to and during an emergency. Response activities are short-term measures to save lives, protect property and meet basic human needs. Counties should have residents prepared to tackle the first 72 hours of a disaster on their own. Residents should know what to do in case of an emergency, from having the necessary supplies to knowing the nearest evacuation route and emergency shelter locations. A county can measure the success of its mitigation and preparation based on the response phase.

The Recovery Phase

The recovery phase happens directly after an emergency incident. Planning and mitigation are necessary to ensure recovery efforts are coordinated and focused on long-term stabilization, with lessons learned from the incident incorporated into recovery plans. Recovery can last for months or years depending on the extent of damages. Recovery efforts work to return county physical and economic life to a new normal, or even safer and better than before the emergency event.

Mitigation

Analyzing & Reducing Vulnerabilities

Counties must regularly analyze hazard-related data to determine areas for improvement with relation to the safety and resilience of county residents and properties. This analysis should include the identification of potential challenges (e.g. how to protect vital county records and floodplains), problem areas and solutions (e.g. buyout programs). It is good practice to involve local residents in the identification of local problem areas that the county has not yet identified. It is also important to engage with local business and nonprofits as many key resources such as utilities and hospitals may not be county owned.

Floodplain Management

A county’s floodplain is not static. It changes as land is developed, weather patterns alter and technology and geospatial techniques improve. A county’s flood map, or Flood Insurance Rate Map (FIRM), depicts areas near major streams that have a specific risk of flooding. Counties must work closely with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to ensure FEMA’s maps on record match the county’s maps and risks as its floodplain shifts.

There are a number of actions counties can take to help mitigate damage to homes and businesses in flood-prone areas, such as: acquiring damaged homes or businesses; relocating structures; returning property to open space, wetlands, or recreational use; and, if applicable, improving the county’s National Flood Insurance Program Community Rating System class. According to a report by the National Institute of Building Sciences, flood mitigation efforts like buyouts, elevations, flood-proofing and other measures have a 5:1 financial payback.

National Flood Insurance Program

The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) was created to help provide a means for property owners to financially protect themselves in the event of a flood. The NFIP offers flood insurance to homeowners, renters and business owners if their community participates in the NFIP. Participating communities agree to adopt and enforce ordinances that meet or exceed FEMA requirements to reduce the risk of flooding. Learn more at www.FloodSmart.gov.

Community Rating System

The National Flood Insurance Program’s (NFIP’s) Community Rating System (CRS) is a voluntary incentive program that recognizes communities for implementing floodplain management practices that exceed the Federal minimum requirements of the NFIP to provide protection from flooding. In exchange for a community’s proactive efforts to reduce flood risk, policyholders can receive reduced flood insurance premiums for buildings in the community. There are 10 CRS Classes. Class 1 requires the most credit points and provides the largest flood insurance premium reduction (45 percent), while Class 10 means the community does not participate in the CRS, or has not earned the minimum required credit points, and residents receive no premium reduction. Learn more on the CRS page on www.FloodSmart.gov.

Buyout Programs

Flood buyout, or property acquisition, programs enable local governments to purchase eligible homes prone to frequent flooding from willing, voluntary owners and return the land to open space, wetlands, rain gardens or greenways. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Storm Water Services, a joint municipal/county stormwater utility established in 1992, has had a locally-funded flood buyout program since 1999. When the buyout program was initially established, a portion of the utility fees, which are based on impervious acreage per parcel, were leveraged against FEMA dollars through a variety of grant programs. This strategy allowed the utility to stretch its money significantly in early years as it prioritized the proactive purchase of high-risk eligible homes.

Today, the county funds its buyout program almost entirely through local funding. Properties are prioritized for buyout based on their flood risk and the mitigation benefits to the community. Key to the program’s success is its ability to generate fairly steady revenue through the county’s stormwater utility fee. In total, the county has purchased nearly 400 flood-prone buildings, leading to the relocation of nearly 700 families and businesses, the return of 185 acres to public open space and an estimated savings of $25 million in losses to date and $300 million in future losses.6

IT CAN TAKE UP TO 2 YEARS TO RECEIVE FEDERAL FUNDS FOR BUYOUTS.

Retrofit Programs

Structural retrofitting is another strategy that can lessen the personal and community impacts of flooding. Flood-related retrofitting measures include raising a house higher off of the ground, putting in flood vents for crawl spaces and moving critical building infrastructure (furnaces, duct work, HVAC systems, etc.) from the ground into an attic space. Charlotte-Mecklenburg County created its retroFIT grant program in 2015 to fill the gap in its services to properties that were either ineligible or lower on the priority list of the aforementioned buyout program. To encourage residents with property in the regulated floodplain to make their houses more resistant to flood damage, the utility set aside a small portion of funding to provide competitive mitigation grants and technical assistance to support owners’ flood-proofing measures. Through its marketing for the retroFIT program, the county has increased residents’ awareness of flood risk. Six projects have received funding so far, but over 100 applications have been submitted to the program. Once completed, these mitigation projects can lead to lower flood insurance rates and reduced flood damage to these retrofitted properties, leading in turn to lower overall post-disaster economic impacts for the county.

Source: U.S. Geological Survey.

Building Codes and Zoning

Changes to and enforcement of local building codes and zoning regulations are two additional ways that counties can lessen damages from disasters and lower insurance costs. Types of flood mitigation code changes include higher freeboards and buffer zones and requiring the use of green infrastructure to reduce runoff in new development and redevelopment projects. A freeboard is a construction standard that requires that the lowest level of a building (i.e. its basement or first floor) be at least 1 foot higher than the federal minimum standard, or base flood elevation.7 Floodplain zoning to reduce flood damage can include laws to limit or disallow people from building or development on the floodplain.8 Ideally, these changes are incorporated into official long-range plans.

Due to its higher standards such as a 2-foot elevated freeboard and other mitigation efforts, Thurston County, Wash. obtained a CRS Class 2 in 2016. This not only helped lower insurance costs for local residents by 40% but also meant after extensive flooding in 2015 when surrounding counties were declared disasters areas Thurston County was not.

Education and Outreach

A SIMPLE WAY TO MAXIMIZE OUTREACH IS TO INCLUDE YOUR LOCAL CHAMBER OF COMMERCE IN DISASTER DRILLS.

Education and outreach to the public, local businesses and county officials and staff is important in order to reduce loss of life, severity of injury and destruction of property in case of an emergency. It is important for everyone to understand—and agree on—the potential hazards and disasters the county is prone to as well as the measures they should take to protect their personal property and safety.

Outreach to the Public and Local Businesses

Counties typically invest in the education of area residents and businesses on emergency management and stormwater and flood risks strategically throughout the year. Modes of communication include billboards, radio spots, public meetings, civic engagement events, school visits, social media and direct mailers, to name a few. General media campaigns include slogans such as “Turn around don’t drown.” Civic engagements events range from disaster drills to activities such as Leon County’s (Fl.) frequent “Build Your Bucket” events, which seek to educate county residents on all hazards disaster preparedness.9 The first 250 participants receive a free 5-gallon bucket containing essential disaster preparedness items such as duct tape, first aid kits, flashlights, and a list of contacts to use in the case of an emergency. In a more targeted approach, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Storm Water Services, thanks to its extensive flood mapping, creates customized mailers for individual homes within Mecklenburg County to let owners know when they are eligible for various local grant programs; last year it sent out 19,000 brochures.10

Education of Local Elected Officials and Staff

It is critical that local elected officials understand emergency management in order to make informed decisions on behalf of the county and its residents and business. To do this, elected officials must take the time to participate in county emergency drills, read—and understand—the county’s hazard mitigation plan and participate in education sessions.

ELECTED OFFICIALS MUST TAKE THE TIME TO PARTICIPATE IN COUNTY EMERGENCY DRILLS.

The Thurston County (Wa.) Emergency Management Council was created via interlocal agreement in 1993 to coordinate local emergency management activities for the county, cities and tribes within Thurston County. The Emergency Management Council brings together all the emergency managers in the county, including emergency managers from two tribes and the cities within the county - even though Thurston County does not currently contract with the cities for emergency management services. Since 2013, the council has held executive seminars twice a year to educate local elected officials, key decision makers and local planning directors and infrastructure and utility providers on the concepts of disaster recovery. Seminars topics have explored: How does the county work through and make decisions about recovery? How should it include the public in the conversation? This focus on recovery is actually its own form of mitigation. To date, the county has held nine seminars covering a variety of hazards, including floods, earthquakes, volcanos and winter storms. As a direct result of the seminars, more stakeholders are asking about recovery, and the county is applying to do a recovery exercise with the FEMA Emergency Management Institute. Additionally, local jurisdictions within the county are better coordinating to make joint decisions. Beyond the executive seminars, county departments have regular briefings and board meetings with local elected officials, especially when there is turnover within the board.

Preparedness

Planning

Planning provides the framework for all other preparedness and response activities. Plans are meant to set priorities and be flexible enough to address all potential hazards and conditions. Plans should identify tasks and purposes and determine which personnel and equipment are necessary to accomplish them. Using the Whole Community approach, all relevant stakeholders necessary to execute the plan should be involved in the development process to ensure coordination, understanding and buy in. The most common types of emergency plans are Comprehensive Emergency Management Plans and Hazard Mitigation Plans. They work best when integrated to ensure activities are consistent with one another and not working at cross-purposes.

Plans, policies, regulations and budgets should be evaluated periodically for consistency with flood resilience goals and each other. This should include a review of the county’s finance and human resources policies. FEMA may not reimburse some costs for up to a year. County leaders should determine whether they have enough reserves on hand to accommodate the extra spending required in a disaster. A good benchmark is a 25% reserve. It is also necessary to review county policies against FEMA reimbursement rules. For example, if the county does not have an official policy in place to pay exempt staff overtime in a disaster event, FEMA will likely not reimburse these costs.

Comprehensive Emergency Management Plans

In compliance with state laws, counties must develop comprehensive emergency management plans (CEMP) or emergency operations plans (EOP) to address how they will deal with emergencies and disasters. The two terms are not interchangeable. A county’s CEMP should both establish a framework for mitigation, preparation, response and recovery and specify the roles and responsibilities of county agencies and officials as well as state and federal agencies and volunteer organizations. An EOP focuses on the second, and can be contained within a CEMP. FEMA has created a national template with standards and principles in the National Incident Management System (NIMS).15 States can choose to adopt NIMS or create their own standards. All plans must be updated in accordance with state law. A common component of a CEMP is a disaster recovery plan.

Local Hazard Mitigation Plans

In compliance with federal planning laws, regulations and guidance, communities must prepare hazard mitigation plans and have them approved by FEMA to be eligible to receive federal funding for mitigation and other non-emergency disaster projects. Hazard mitigation plans are documents that aim to identify, assess and reduce the long-term risk to life and property from a range of natural hazards. They must be updated every five years, and can be stand-alone documents or integrated in a community’s local comprehensive plan. Counties can prepare hazard mitigation plans on their own, with other jurisdictions within the county or with other counties as part of a multi-county region.

Mutual Aid Agreements

Mutual Aid Agreements are important mechanisms to secure county operations in times of emergency because they can authorize assistance between two or more neighboring counties, jurisdictions, and/or states – and also between private sector entities, NGOs and other community partners. They put in place formalized systems that allow for expedited assistance and acquisition of equipment and personnel in times of emergency. For example, following the one-two-punch of Tropical Storm Julia on September 21 and Hurricane Matthew on October 6, 2016, swift-water rescue teams and equipment from counties across North Carolina came to assist Bertie County in their disaster response. The county was also able to obtain a replacement generator within hours after a generator in one of its emergency shelters malfunctioned, allowing them to provide a safe place for residents during the storm. Although the county estimates that these storms resulted in a combined total of about $25 million in damage and recovery costs, their foresight in establishing a mutual aid agreement with surrounding counties allowed for the quick dispatch of necessary resources that prevented even further loss of life and property.

Collaborative Working Groups

It is important for county governments and government departments to not act in silos when preparing for future emergencies. All stakeholders should be given a chance to contribute to the conversation when decisions are being made that effect the future of the county as a whole. In Bexar County, Texas, the Bexar Regional Watershed Management partnership was created in 2002 to provide improved coordination in planning and capital improvement programs for flood control, storm water management and water quality.11 The partnership is managed by the Bexar County Commissioners Court, the San Antonio City Council and the San Antonio River Authority (SARA) Board of Directors, and includes the 20 suburban cities within Bexar County. It has three committees overseeing its programs, one comprised of local elected officials, one of local public works staff and one of local citizens. This ensures manpower and resources are allocated more effectively and efficiently in line with the public opinion. Through its work, the partnership has created improved watershed models and flood maps that “provide a much-improved picture of the flood risk in all areas of the county.”12 The partnership also supported the completion of Bexar County’s 10-year, $500 million capital improvement program that reduced the impact of flooding county-wide.

It is also important to coordinate inter-departmentally within the county government. Thurston County, Wa. has bi-monthly meetings with its Public Works and Engineering Emergency Support Function group. At the meetings, they focus on a different preparedness topic each time, such as high ground water analysis, flooding or what grants they are working. The four main county divisions that participate in the group are Emergency Management, Public Works, Resource Stewardship, and the Environmental Health program of Public Health & Social Services. Multiple departments within each division participate in the meetings, such as debris disposal from public works, long range planning and stormwater management from resource stewardship, and water quality from public health. This coordination allows the county to better plan for the provision and restoration of essential services during an emergency. Thurston County also has a number of collaborative workgroups to plan, train and exercise together. Two of those workgroups are the Thurston County Emergency Management Council (see Education of Local Elected Officials and Staff section) and the Disaster Assistance Council, which works as the local Volunteer Organizations Active in Disaster.

Relevant Preparedness Stakeholders:

- Individuals and families

- Businesses

- Faith-based and community organizations

- Nonprofit groups

- Schools and academia

- Media outlets

- All levels of government, including state, local, tribal, territorial, and federal partners.

Volunteer Organizations Active in Disaster

Volunteer, or Community, Organizations Active in Disaster (VOADs/COADs) were formed as a way to coordinate disaster response and avoid duplication of and gaps between efforts to meet a community’s needs—both governmental and non-governmental. They share knowledge and resources and are composed of organizations that help disaster survivors and their commuwwnities through all phases of a disaster. These organizations include civic groups, businesses, faith based associations, individuals and government agencies. Learn more at www.nvoad.org.

Training and Exercises

Training and emergency exercises are valuable tools when preparing county personnel and residents for potential emergency situations. They ensure that residents and staff understand proper protocols and procedure, and provide an opportunity to evaluate county emergency plans in a controlled setting. Emergency management exercises can be targeted to specific groups or for the public at-large. They range from Community Emergency Response Team, or CERT, exercises on search and rescue with 10 to 25 participants to statewide hurricane exercises with over 250 participants. CERT is a training program for residents who are interested in taking an active role in neighborhood preparedness for disasters. It prepares individuals to be ready to assist in times of disaster, targeting hazards that are most likely to impact their county. Another program designed to help with neighborhood preparedness is the Map Your Neighborhood (MYN) program. MYN trains residents to identify and create lists of their neighborhood’s natural gas and propane tanks locations, homes with elderly, disabled or children, and helpful skills and equipment each neighbor has, to name a few, in order to work together as a team during a disaster. Local elected officials’ participation in the training and exercises is critical.

Work with Faith-Based Communities

Many counties have established relationships with their faith-based communities in order to coordinate response efforts and educate congregation members on emergency management. Thurston County, Wa. and Santa Rosa County, Fl. have both worked with their faith-based communities since the mid-2000s. Thurston County focuses its education and outreach on how faith-based communities can be a resource and what their role could be in the community during and after disaster, on both a personal and corporate level. They have historically held between two and four meetings per year at different locations on a variety of topics, bringing all the faith-based communities together with countywide emergency managers. Meetings have included trainings on how to become a Red Cross emergency shelter, HAM radio and first aid. The county has compiled a listserv of over 200 people and sends out regular mailers to 164 pastors within the county.

Santa Rosa County started its work with faith-based communities following Hurricanes Ivan (2004) and Dennis (2005).13 These two hurricanes caused a combined estimated total of $21 billion in property damage and led to 28 direct and 44 indirect deaths across the Southeast, but primarily in Florida. The devastation was so overwhelming that the county could not handle all the response and recovery work on its own. Local faith-based communities stepped in to help by bolstering feeding stations around the county. The county’s emergency management team quickly recognized how much of a resource its local faith-based communities could be. Today, the county works with congregations one-on-one to ensure the county is serviced equally. Tasks include establishing feeding stations and working with congregations to build senior evacuation kits and form search teams to keep tabs on their members during an emergency incident.

Improving Communications

It is crucial that counties have a plan for how to communicate with their residents before, during and after a disaster. This includes having multiple, reliable means to communicate public information and warnings about impending incidents. As technology has developed, the means and modes of communication have improved and multiplied. Ten years ago, Volusia County, Fl. Emergency Management would prepare and release hardcopy disaster preparedness guides as newspaper supplements. Today, it has developed a disaster preparedness video with its local public television station that is available on YouTube. The Disaster Preparedness Guide video has been shared at all public outreach presentations, which occur approximately 150 times a year, and online through the county’s website and social media accounts.

DOWNLOAD THE FEMA MOBILE APP TO ACCESS TOOLS AND TIPS FOR WHAT TO DO BEFORE, DURING AND AFTER

Social media has become a vital method of communication for county government, especially during emergencies. Many counties, including Volusia County, now push out warnings via social media before severe storms and other impending emergency incidents, whereas before they would rely primarily on local news and newspapers to issue alerts. To maximize the spread of a message, counties must look to utilize all available means. In its recent evaluation of the county’s response to Hurricane Hermine, Leon County, Fl. decided in the future it would use not only the county’s social media accounts but also those of its elected officials and staff. While these new technologies are vital resources, the old modes must still be utilized as well. Sometimes in a critical disaster, a simple paper newsletters distributed by hand works best.

Florida • Bradford, Brevard, Broward, Clay, Duval, Flagler, Indian River, Lake, Martin, Nassau, Orange, Osceola, Palm Beach, Putnam, St. Johns, St. Lucie, Seminole, Volusia, Baker, Citrus, Glades, Hendry, Hernando, Highlands, Marion, Miami-Dade, Monroe, Okeechobee, Polk, Alachua, Columbia, Dixie, Franklin, Gadsden, Gilchrist, Hillsborough, Jefferson, Lafayette, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Manatee, Pasco, Pinellas, Sarasota, Sumter, Suwannee, Taylor, Union, Wakulla

Georgia • Brantley, Bryan, Bulloch, Camden, Candler, Chatham, Effingham, Emanuel, Evans, Glynn, Jenkins, Liberty, Long, McIntosh, Pierce, Screven, Tattnall, Toombs, Ware, Wayne, Appling, Atkinson, Bacon, Burke, Charlton, Clinch, Coffee, Echols, Jeff Davis, Treutlen

Iowa • Allamakee, Benton, Black Hawk, Bremer, Buchanan, Butler, Cerro Gordo, Chickasaw, Clayton, Delaware, Des Moines, Fayette, Floyd, Franklin, Howard, Linn, Mitchell, Winneshiek, Wright

Louisiana • Acadia, Ascension, Assumption, Avoyelles, Cameron, East Baton Rouge, East Feliciana, Evangeline, Iberia, Iberville, Jefferson Davis, Lafayette, Livingston, Pointe Coupee, St. Charles, St. Helena, St. James, St. John the Baptist, St. Landry, St. Martin, St. Tammany, Tangipahoa, Vermilion, Washington, West Baton Rouge, West Feliciana, Allen, Beauregard, Bienville, Bossier, Caddo, Calcasieu, Caldwell, Catahoula, Claiborne, De Soto, East Carroll, Franklin, Grant, Jackson, Lafourche, La Salle, Lincoln, Madison, Morehouse, Natchitoches, Ouachita, Rapides, Red River, Richland, Sabine, Union, Vernon, Webster, West Carroll, Winn, Concordia, Plaquemines, St. Mary, Terrebonne

Maryland • Howard

Minnesota • Blue Earth, Fillmore, Freeborn, Goodhue, Hennepin, Houston, Le Sueur, Rice, Steele, Waseca

Missouri • St. Louis, Barry, Barton, Bollinger, Camden, Cape Girardeau, Cedar, Cole, Crawford, Dade, Dallas, Douglas, Dunklin, Franklin, Gasconade, Greene, Hickory, Howell, Iron, Jasper, Jefferson, Laclede, Lawrence, Lincoln, McDonald, Maries, Mississippi, Morgan, New Madrid, Newton, Osage, Ozark, Pemiscot, Perry, Phelps, Polk, Pulaski, Reynolds, St. Charles, St. Clair, Ste. Genevieve, St. Francois, St. Louis, Scott, Shannon, Stoddard, Stone, Taney, Texas, Washington, Webster, Wright, Audrain, Boone, Butler, Callaway, Carter, Christian, Clark, Cooper, Dent, Howard, Lewis, Madison, Marion, Miller, Moniteau, Montgomery, Oregon, Pike, Ralls, Ripley, Vernon, Warren, Wayne

Mississippi • Bolivar, Claiborne, Clarke, Coahoma, Covington, Forrest, George, Greene, Holmes, Issaquena, Jefferson Davis, Jones, Lamar, Lawrence, Leake, Leflore, Lincoln, Marion, Panola, Pearl River, Perry, Quitman, Sunflower, Tallahatchie, Tate, Tunica, Walthall, Washington, Wayne

North Carolina • Anson, Beaufort, Bertie, Bladen, Brunswick, Camden, Carteret, Chatham, Chowan, Columbus, Craven, Cumberland, Currituck, Dare, Duplin, Edgecombe, Franklin, Gates, Greene, Halifax, Harnett, Hertford, Hoke, Hyde, Johnston, Jones, Lee, Lenoir, Martin, Montgomery, Moore, Nash, New Hanover, Northampton, Onslow, Pamlico, Pasquotank, Pender, Perquimans, Pitt, Richmond, Robeson, Sampson, Scotland, Tyrrell, Wake, Warren, Washington, Wayne, Wilson, Alamance, Caswell, Davidson, Davie, Durham, Forsyth, Granville, Guilford, Orange, Person, Randolph, Rockingham, Stokes, Surry, Vance, Yadkin

Oklahoma • Caddo, Comanche, Cotton, Garvin, Grady, Jackson, Stephens, Tillman

Pennsylvania • Centre, Lycoming, Sullivan

South Carolina • Allendale, Bamberg, Barnwell, Beaufort, Berkeley, Calhoun, Charleston, Chesterfield, Clarendon, Colleton, Darlington, Dillon, Dorchester, Florence, Georgetown, Hampton, Horry, Jasper, Kershaw, Lee, Marion, Marlboro, Orangeburg, Richland, Sumter, Williamsburg, Catawba Indian Reservation, Abbeville, Aiken, Anderson, Cherokee, Chester, Edgefield, Fairfield, Greenville, Greenwood, Lancaster, Laurens, Lexington, McCormick, Newberry, Oconee, Pickens, Saluda, Spartanburg, Union, York

Texas • Austin, Bandera, Bastrop, Bosque, Brazoria, Brazos, Brown, Burleson, Caldwell, Callahan, Coleman, Comanche, Eastland, Erath, Falls, Fayette, Fisher, Fort Bend, Grimes, Hall, Hardin, Harris, Hidalgo, Hood, Houston, Jasper, Kleberg, Lee, Leon, Liberty, Madison, Montgomery, Navarro, Palo Pinto, Parker, Polk, San Jacinto, Somervell, Stephens, Throckmorton, Travis, Trinity, Tyler, Walker, Waller, Washington, Anderson, Cass, Cherokee, Colorado, Coryell, Harrison, Jones, Milam, Smith, Upshur, Van Zandt, Wharton, Wood, Angelina, Gregg, Henderson, Lamar, Limestone, Marion, Newton, Orange, Red River, Sabine, San Augustine, Shelby

Virginia • Isle of Wight, Southampton

Washington • Clallam, Clark, Cowlitz, Grays Harbor, Jefferson, Lewis, Mason, Pacific, Skamania, Wahkiakum

Wisconsin • Adams, Chippewa, Clark, Crawford, Jackson, Juneau, La Crosse, Monroe, Richland, Vernon

West Virginia • Braxton, Clay, Fayette, Gilmer, Greenbrier, Jackson, Kanawha, Lewis, Lincoln, Monroe, Nicholas, Pocahontas, Randolph, Roane, Summers, Upshur, Wayne, Webster

Response

Early Response Coordination

In times of emergency, it is vital that all county personnel know what they need to do, the proper procedure for doing so, who they need to coordinate with outside of their department or the county to get things done and how to reach them. To help with this, counties should be sure to keep an up to date list of county staff, including cell phone numbers. A few days prior to Hurricane Matthew making landfall in North Carolina, Wayne County called a meeting of all its department heads to go over the County’s Emergency Operations Plan to ensure everyone knew their roles and had an opportunity to ask any questions. This set the county on the right path to execute its other response strategies effectively.

Public Health and Safety

Local police, fire, emergency medical services (EMS), emergency management, public health and medical providers, public works, and other community agencies are often the first to be notified about a threat or hazard or to respond to an incident.14 Public health and safety activities range from search and rescue and crime scene investigation to removal of threats from the environment and decontamination following a chemical, biological or radiological attack or spill. It is important that all county public health and safety personnel are trained in emergency response and know the proper protocols and procedures. It is also important to ensure that all county residents have access to county public health and safety personnel during a disaster. During Hurricane Matthew, Wayne County knew it was highly likely that U.S. Highway 70, which bisects the county, would flood. In response, the county sheriff’s office set up a temporary office on the south side of the highway so there would be no service interruptions. Additionally, emergency medical services set up temporary offices south of the river, and the county partnered with Wilson County to the north to use their landfill and trucks to pick up trash from convenience centers in the northern parts of the county.

Evacuations

When a hazard reaches the point where evacuation is necessary, counties must make sure their residents know where, when and if they need to evacuate. There are a number of strategies counties can employ to spread the message, including posts on local TV and radio stations, social media, email and reverse 911. Reverse 911 gives counties the ability to push emergency messages out to residents by phone; counties generate call lists based on protocols (e.g. internal identification of elderly and special needs residents) and through sign up links (e.g. external self-identification by residents). The most effective means of evacuation, however, is still door-to-door visits by local personnel, typically volunteer firefighters, who can check on residents and spread the message of expected conditions. During Hurricane Matthew, Craven County, N.C. had county staff go door-to-door with flyers highlighting the damage wrought on the county by Hurricane Floyd in 1999 as an example of what could happen if they did not leave. They encountered three types of residents, those who were ready and willing to leave, those who were not and those who could not without assistance, whether due to lack of transportation, frailty or special needs. If county residents are unable to evacuate themselves, counties must have plans in place for their evacuation and shelter. These plans usually include the use of local transportation systems and school buses to transport people from their homes to the county’s emergency shelters.

Emergency Shelters & Services

Emergency Shelters provide a safe place for residents to harbor during and immediately following a disaster. Counties typically partner with national relief organizations, such as the American Red Cross, United Way and the Salvation Army, to develop their emergency shelter systems. These organizations also help counties to provide residents with food, supplies, health services and the development of individual recovery plans, including the identification of available recovery resources, during a disaster. Emergency shelters open on a case-by-case basis depending on need in each section of the county, usually mass loss of power and flood water safety concerns. It is important that each identified emergency shelter is equipped to operate in a disaster, with operating generators, etc. Typical emergency shelter locations are community centers and schools. Thurston County looks to use community centers first because in order for operations to return to normal from August to June schools must be in session. On the other hand, Craven County, N.C. prioritizes the use of schools because they are built to high security standards, are located at strategic geographic intervals, and typically have generator power and a base food supply.

Animals and Agriculture

Emergency shelters do not usually accept pets, which can lead many people to make the decision to stay behind in their homes rather than evacuating so as to not abandon their pets. This refusal to evacuate can cause additional recovery issues down the road when people and their pets have to be rescued from rising flood waters. With this in mind, it is important for counties to develop disaster plans for animals and agriculture, most importantly plans for evacuation and sheltering. Strategies for sheltering include partnering with local SPCAs or humane societies to designate them as an emergency shelter for pets, identifying at least one emergency shelter that will accept pets and working with local hotels to have “no pet” policies temporarily lifted. Education of county residents on personal planning for pets in disasters is also vital. Cumberland County, N.C. advises locals to research what to do for their pets in case of an emergency beforehand.15 This includes knowing the county’s policy on pet sheltering, checking to see if the pet’s vet will house animals in case of an emergency and having a current photo of and identification tags and survival kits for each pet.

Volunteers

Trained emergency responders cannot cover all a county’s needs in a disaster. Volunteers are necessary to fill the gaps and help return the county to a semblance of order. They can provide support to activities ranging from helping with debris removal and construction to acting as an interpreter or communications runner. Volunteers can be both local and visitors, trained or untrained, unaffiliated or affiliated with volunteer groups. Last May, Santa Rosa County started an annual “Serve Day” to encourage volunteerism and recruit disaster volunteers. At the inaugural event, 700 residents participated in volunteer projects across the county.

It is important to have a plan for how to manage each type of volunteer. A number of counties process volunteers using the Volunteer Reception Center (VRC) model, including Santa Rosa and Leon Counties. In times of disaster, VRCs are set up around the county to register spontaneous, unaffiliated volunteers and refer them to local agencies based on their skills sets. This helps to expand the capacity of major disaster relief efforts, and motivate these spur-of-the-moment volunteers to join a relief agency before the next disaster occurs. After Hurricane Hermine last August, while it did not have to open a VRC, Leon County utilized 43 volunteers and 19 employees, who answered the Citizen Information Line (CIL), in its Emergency Operation Center (EOC). The EOC was activated for 110 hours consecutively, with volunteers and staff contributing 1,262 hours. Additionally, 62 volunteers, who called the CIL wanting to help were referred to partner response and recovery agencies to support their operations.

Recovery

Restoration of Critical Services, Infrastructure and Government Systems

It is vital to county operations for critical services, infrastructure and government systems to be restored in as minimal time as possible. Critical services include electric power, water, natural gas, sewer and telephone. Critical infrastructure includes roads, bridges, municipal buildings, schools and hospitals. Critical government systems are those necessary to ensure the performance of essential government activities. They might include law enforcement, public works, public health, courts and human services. Not all critical services, infrastructure and systems are governmental, some, such as utilities and hospitals, might be non-government operated. It is important for the county to work with these non-governmental entities to ensure these critical services and facilities are operational to meet county needs.

Debris Cleanup and Removal

According to FEMA, comprehensive debris management plans are critical to efficient post-disaster recovery efforts. Debris removal is costly and can take months to complete even with plans in place prior to a disaster event. It is advisable to have a contract for debris removal in place before an emergency. Procuring a FEMA-approved contractor can take weeks on the short end and months on the long end—and time is one thing counties cannot afford to lose during a disaster recovery situation. Having an active contract in place allowed Beaufort County, S.C., to initiate debris monitoring and hauling services within days following Hurricane Matthew. The county’s contractor was on standby even before the storm hit. When negotiating its debris removal contracts, Beaufort County bids in five-year increments, and looks to hire companies that are sufficiently sized so as to not be overcommitted when called to respond to a storm event. The county was also able to negotiate with FEMA for reimbursement of the cost of the removal of debris from over 90 gated communities located on private property within the county.

Recovery Site

It is helpful to have a designated site for residents to come to for advice on the recovery of their personal and business property. Boulder County in response to major flooding in 2013 created the Boulder County Flood Recovery Center to house key recovery subject matter experts in one location to aid in collaboration and communication as well as make it easier for residents to get the answers they need. This effort not only helped ease the confusion and frustration of flood-impacted residents but also brought many county departments together, increasing inter-department coordination on projects, enhancing customer service and fostering greater trust and respect for Boulder County government in residents. The Boulder County Flood Recovery Center houses staff that focuses on permitting, private access, rebuilding, community resiliency, case management, financial assistance, public outreach, and home buyout and demolition. Since its creation the recovery center has: issued 497 building permits; conducted 104 hazard mitigation reviews for the rebuilding of destroyed or severely damaged structures in a safe manner, and 42 limited impact special reviews for earthwork projects in flood hazard areas; awarded Home Access grants to 34 applicants for a total of 26 projects, and Clearance and Demolition grants to 37 applicants for a total of 32 projects; negotiated 48 home buyouts; held over 60 meetings in neighborhoods totaling over 2,000 people; and handled 440 cases with total awards over $7 million dollars.

Temporary Housing

Temporary housing is necessary after a disaster to restore emergency shelter facilities to their original intended functions. It is typically a four-step process including housing residents at emergency shelters. Following shelters is short-term temporary housing (i.e. rooms with family or friends or hotels) and then long-term temporary housing (i.e. apartments or mobile homes). The last step is getting residents relocated or back in their own repaired, and hopefully retrofitted, homes. In North Carolina, following Hurricane Matthew, teams with representatives from local, state and federal emergency management agencies, American Red Cross, Division of Social Services, the U.S. Housing and Urban Development, and the Volunteer Organizations Active in Disaster met with displaced county residents and families to help them form short-term and long-term housing plans. The transition from emergency shelter to temporary housing can take anywhere from one hour to a few weeks.

Long-Term Rebuilding and Mitigation Measures

And the cycle continues…

Advice from County Leaders

On stakeholder relationships and coordination…

- Coordinate and partner with local, city, state and national stakeholders, and both government agencies and non-governmental organizations. It is important to meet with all stakeholders before an event in order to ensure a coordinated local response and to act as one team during the event.

- Maintain good relationships with city officials, school board commissioners, community colleges, etc. within your county. If relations are strained prior to a disaster, it can cause problems during response and recovery.

- Establish inter-departmental relationships. The more familiar county department employees are with one another before a disaster event, the better they will work together responding to county and county resident needs during the disaster.

- Establish community buy-in to increase support of local projects and participation in community events and disaster activities. If the community does not believe in the work, it will not get very far.

- Engage the community so that drills and preparation have some fun and even competition – the Great ShakeOut is a good example.

On education and outreach…

- Educate your citizens not only on disasters but also what they can realistically expect from the county in a disaster situation. This will help decrease frustration during the response and recovery phases.

- Use talking about one type of disaster as an open door to talk about another type of disaster. For example, if you have a tsunami exercise, relate it to hurricane storm surge.

On mitigation…

- Look at the watershed as a whole. You do not want the mitigation work you do in one area of the county to negatively affect another area downstream.

- Establish a continuous stream of local funding for regular mitigation and resilience activities. The backbone of resilience is resilient funding. As counties cannot rely on state and federal money, it is beneficial to establish dedicated funding if and when possible.

- Have an aggressive public outreach campaign. The average citizen does not think about emergency management on a daily basis. It is important to spread the county’s emergency management message clearly and repeatedly in order to get the public involved in the county’s emergency management program.

- Look beyond past and current floodplains to future projections in order to minimize future damages and calculate the allocation of resources most effectively. Mapping to existing conditions isn’t enough.

- Streamline review processes. Federal, state and local regulatory agencies typically have varying regulatory standards for flood control. If the county, and any local partners, can get their processes streamlined, it is helpful for project approval.

- Clear county drains and stream beds of litter and debris regularly. You do not want a blockage to stop the flow of water during a storm and cause major problems. Preventative maintenance is key.

On preparedness…

- Pre-plan. Pre-plan. Pre-plan. Remember to incorporate lessons from past experience into new plans.

- Push flood insurance. It is the first line of defense in recovering from a flood. Engage your banking and insurance community to assist you in this effort as it is to their benefit too.

- Look into FEMA’s High Water Mark Initiative. It is a community-based program to increase local awareness of flood risk. It includes activities such as posting High Water Mark signs in prominent places and conducting ongoing education on local flood risk.

On response…

- Send out daily emails with disaster updates, making sure to city managers and school board.

- Work with your local media. They are an asset. It is beneficial to have briefings with them and put out local media releases regularly. There is still a segment of the population that really relies on what the news media reports.

On recovery…

- Request to have one FEMA representative with authority stay the same throughout the entire process, once a disaster is declared and FEMA sends a team to help. This establishes continuity, and saves time as you will not have to repeatedly explain the situation as teams rotate through.

- Make sure you have a debris recovery plan in place pre-disaster. It can be hard to get a FEMA approved contractor in a timely manner after the fact.

- Consider the formation of a disaster recovery council. The council should include key county staff, such as HR and legal, to make sure all details are being attended. It should meet regularly prior to an event and frequently in response and recovery.

- Take time to debrief staff early after the disaster and encourage them to rest along the way. Long term recovery for larger disasters can take a toll on staff and community.

- Don’t overlook non-disaster related grant programs. All sources of funding are fair game.

In general…

- Don’t recreate the wheel. When possible, work with specialty organizations and your local colleges and universities. This applies to any phase of emergency management from data collection during preparedness to volunteer management during response.

- Create toolkits and fact sheets on important processes and strategies (e.g. building codes and community recovery management). FEMA has great resources to help your county build its own toolkits.

- Review the eight principles of emergency management and follow them.16

Conclusion

Counties must prepare for all hazards in order to protect the health and safety of their constituents, property, infrastructure systems and economies from the impact and cost of disasters. Disasters can strike any county at any time. It is important for county leaders to understand the emergency management cycle and the multitude of strategies available to mitigate and prepare for and respond to and recover from disasters. The strategies listed here are not exhaustive but rather provide a glimpse of the breath of available strategies. By using these, and other, strategies and by collaborating with federal and state agencies, national relief organizations and local municipalities, businesses and residents, counties can increase their resiliency to disasters, saving lives and money.

Additional Resources

Links to Featured Counties Webpages

Boulder County, Colo.

http://www.bouldercounty.org/flood/pages/default.aspx

Escambia County, Fla.

https://myescambia.com/our-services/public-safety/beready

Leon County, Fla.

http://cms.leoncountyfl.gov/Home/Departments/Office-of-Human-Services-and-Community-Partnership/Volunteer-Services

Santa Rosa County, Fla.

http://www.santarosa.fl.gov/emergency/fbp.cfm##

Volusia County, Fla.

http://www.volusia.org/services/public-protection/emergency-management/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_oEbRKeziog

Bertie County, N.C.

http://www.co.bertie.nc.us/departments/em/em.html

Craven County, N.C.

http://www.cravencountync.gov/emergency/emergencymgt.cfm

Cumberland County, N.C.

http://www.co.cumberland.nc.us/emergency_mgmt/pet_planning.aspx

Mecklenburg County, N.C.

http://charlottenc.gov/StormWater/Pages/default.aspx

Wayne County, N.C.

http://www.waynegov.com/315/Emergency-Management

Beaufort County, S.C.

http://www.bcso.net/Emergency%20Management/index.php

Bexar County, Texas

http://www.bexarfloodcontrol.org/

Thurston County, Wash.

http://www.co.thurston.wa.us/em/

Links to Relevant FEMA Webpages

https://training.fema.gov/emi.aspx

https://www.fema.gov/hazard-mitigation-assistance

https://www.fema.gov/high-water-mark-initiative

https://www.fema.gov/mobile-app

https://www.fema.gov/data-visualization-disaster-declarations-states-and-counties

Other Resources

https://www.unitedway.org/local/united-states

http://disaster.salvationarmyusa.org/

Endnotes

1 “Types of Disasters,” RestoreYourEconomy.org, http://restoreyoureconomy.org/disaster-overview/types-of-disasters/.

2 “Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Overview,” NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/.

3 “FEMA Disaster Declarations Summary - Open Government Dataset,” FEMA, https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/28318.

4 “2016: A historic year for billion-dollar weather and climate disasters in U.S.,” NOAA Climate.gov, https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/beyond-data/2016-historic-year-billion-dollar-weather-and-climate-disasters-us.

5 “GUIDE TO EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT AND RELATED TERMS, DEFINITIONS, CONCEPTS, ACRONYMS, ORGANIZATIONS, PROGRAMS, GUIDANCE, EXECUTIVE ORDERS & LEGISLATION,” FEMA, https://training.fema.gov/hiedu/docs/terms%20and%20definitions/terms%20and%20definitions.pdf.

6 “Floodplain Buyout (Acquisition) Program,” Charlotte-Mecklenburg Storm Water Services, http://charlottenc.gov/StormWater/Flooding/Pages/FloodplainBuyoutProgram.aspx.

7 “A Guide for Higher Standards in Floodplain Management,” Association of State Floodplain Managers, www.floods.org.

8 “Floods And Flood Plains,” U.S. Geological Survey, https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/1993/ofr93-641/.

9 “Build Your Bucket, Prepare for Emergencies,” City of Tallahassee, http://www.talgov.com/emergency/News/Build-Your-Bucket-Prepare-for-Emergencies-4907.aspx.

10 “Fiscal Year 2015 Annual Report,” Charlotte-Mecklenburg Storm Water Services, http://charlottenc.gov/StormWater/SurfaceWaterQuality/Documents/15annualreportnov252015.pdf.

11 “About us,” Bexar County Flood Control, http://www.bexarfloodcontrol.org/.

12 “Winter 2004,” Bexar Regional Watershed Management, http://floodsafety.com/media/pdfs/texas/BRWMdetailedfactsheet.pdf.

13 “Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Ivan,” NOAA National Hurricane Center, http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL092004_Ivan.pdf; “Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Dennis,” NOAA National Hurricane Center, http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL042005_Dennis.pdf.

14 “Developing and Maintaining Emergency Operations Plans,” FEMA, https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/20130726-1828-25045-0014/cpg_101_comprehensive_preparedness_guide_developing_and_maintaining_emergency_operations_plans_2010.pdf

15 “Pet Planning,” Cumberland County, N.C., http://www.co.cumberland.nc.us/emergency_mgmt/pet_planning.aspx.

16 “Emergency Management: Definition, Vision, Mission, Principles,” FEMA, https://training.fema.gov/hiedu/docs/emprinciples/0907_176%20em%20principles12x18v2f%20johnson%20(w-o%20draft).pdf.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the following individuals for providing their time and expertise:

- Association of State Floodplain Managers: Chad Berginnis, Executive Director.

- Boulder County, Colo.: Garry Sanfacon, Flood Recovery Manager.

- Escambia County, Fla.: Joy Jones, Division Manager & Assistant County Engineer; and Hon. Grover Robinson, County Commissioner.

- Leon County, Fla.: Jeri Bush, Volunteer Services Director.

- Santa Rosa County, Fla.: Brad Baker, Emergency Management Director; Sheila Fitzgerald, Board of County Commissioners Grants Director; Stephen Furman, Public Works Director; Daniel Hahn, Emergency Management Plans Chief; and Karen Thornhill, Floodplain Manager.

- Volusia County, Fla.: Larry LaHue, Senior Planner.

- Bertie County, N.C.: Hon. Ron Wesson, County Commissioner; and Scott Sauer, County Manager.

- Craven County, N.C.: Jack Veit III, County Manager.

- Mecklenburg County, N.C.: Tim Trautman, Engineering & Mitigation Program Manager.

- Wayne County, N.C.: George Wood, County Manager.

- Beaufort County, S.C.: Josh Gruber, Deputy County Administrator.

- Bexar County, Texas: Bobby Mengden, Bexar County Flood Control Program Director (AECOM); and David Wegmann, Bexar County Engineering Services Manager.

- Thurston County, Wash.: Vivian Eason, Emergency Management Coordinator; and Andrew Kinney, Emergency Management Coordinator.

This report was researched and written by Jenna Moran, program manager, with guidance from Sanah Baig, program director, and Linda Langston, director of strategic relations. To request copies of this publication or other materials about the National Association of Counties, please contact: Jenna Moran, NACo program manager, jmoran@naco.org, 202-942-4224.

ABOUT NACo’S RESILIENT COUNTIES INITIATIVE

Through the Resilient Counties initiative, NACo works with counties and their stakeholders to bolster their ability to thrive amid changing physical, environmental, social and economic conditions. Hurricanes, wildfires, economic collapse, and other disasters can be natural or man-made, acute or long-term, foreseeable or unpredictable. Preparation for and recovery from such events requires both long-term planning and immediate action.