Managing County Workers: Recruitment, Retention and Retirement

Upcoming Events

Related News

Recruitment and MillennialsCounty governments’ restricted funding calls for creative ways to retain employees considering other jobs.

County governments must find ways to compete with other employers for qualified candidates. According to the Center for State and Local Government Excellence, approximately 90 percent of state and local government human resource managers say recruiting qualified personnel with the skills necessary to succeed in public service is the most important workforce issue for their organization.4 Hiring qualified personnel is not a challenge limited to the government — it is the top issue for all employers, both in the private or public sectors, meaning there is more competition amongst hiring entities.

83% of counties have average annual local government -county and municipality- pay less than $47,500.

Job seekers take many factors into consideration when deciding on a place of employment. As employers, local governments are not always able to offer pay that is competitive with the private sector.5 At the same time, 64 percent of non-millennials and 68 percent of millennials value compensation as an important factor in their career.6 Exacerbating this fact is that millennials, who make up one-third of the total U.S. workforce, often view government work as "boring."7 They may instead seek careers with non-governmental organizations or other socially-focused employers to pursue jobs that are related to public service.8

These employment factors — lower pay, perceptions of government workplace, competing options — lead to difficulties for counties in hiring qualified candidates. Counties are faced with long-term vacant positions in an environment where they are already doing more with less. For example, in Volusia County, Fla., the sheriff’s office can have up to 50 vacant positions at any given time due a highly competitive labor market in the county.9 Counties in Minnesota are struggling to fill child protection positions due to increased workloads and the impact this has on an employee’s work-life balance.10 This report highlights a number of county innovative and cost-effective strategies to recruit qualified candidates, including millennials.

Map 1: Average Annual Pay Across Local Government, 2017

County Explorer

San Diego County, Calif.

2015 Population: 3,299,521 2015 Workforce: 17,396 Interviewee: Brandy Winterbottom-Whitney, Deputy Director of Human Resources, San Diego County, Calif.

Note: County workforce represents the number of both full-time and part-time employees. Source: NACo County Explorer, explorer.naco.org

San Diego’s internship program recruits young professionals into county government.

In 2016, San Diego County received nearly 70,000 applications for 3,400 job openings. Brandy Winterbottom- Whitney, Deputy Director of Human Resources, says this is the result of several programs and initiatives created to make San Diego County an attractive workplace to job-seekers. The county partners with local universities through their College Connections program to target young workers and millennials. This program allows students to work part-time in departments throughout the county in fields matching their talent and skills while offering tuition discounts and reimbursements. The county also teamed up with the San Diego Workforce Partnership and Connect2Careers to establish an internship program targeted towards at-risk youth. As part of this program, interns work in different departments for 15 hours per week, which allows them to accommodate their personal and educational schedules. In 2016, 39 interns completed the program, gaining valuable experience and exposure working with San Diego County.

By convening millennial peers, San Diego County learns what matters most to this growing demographic.

In addition to attracting a younger workforce, the county has ten Employee Resource Groups (ERG), which help promote and advance the county’s commitment to diversity in their workforce. These groups, including the African-American Association of County Employees, the Middle Eastern Employee Resource Group and Asian Pacific Alliance of County Employees, among others, serve as key advocates in advancing the county’s vision of an inclusive and diverse workforce. Another ERG, the Emerging Workforce Association, is specifically geared towards millennials. By convening millennial peers through this group, the county learns what matters most to this growing demographic, especially in terms of choosing an employer, and can adapt accordingly.

Source: San Diego County, Calif. Department of Human Resources

Winterbottom-Whitney also points to ways San Diego County is thinking outside of the box with traditional forms of recruitment. For example, their human resources department uses social media to market job openings and, in some cases, produces short videos that give candidates an idea of what their work for the county will look like and their impact on the lives of residents. The county recognizes that millennials want their work to be meaningful.

Another way San Diego County’s HR department handles recruitment is through surveys and post-hiring practices. The county’s human resources department also administers a survey to departments that assesses the level of satisfaction with the recruitment process and quality of applicants. This process ensures that both employee and employer are a strong and appropriate fit for their respective needs.

Henrico County, Va.

2015 Population: 325,155 2015 Workforce: 10,950 Interviewee: Becky Simulcik, Assistant Director of Human Resources, Henrico County, Va.

Note: County workforce represents the number of both full-time and part-time employees. Source: NACo County Explorer, explorer.naco.org

Henrico County gives interns the opportunity to work with departments that complement their career goals.

Making Henrico County, Va. a top-choice employer for younger workers and millennials is a priority for the organization. In 2012, the county formalized their internship efforts by instituting a formal Internship Program and designating an internship coordinator. Under this program, interns are hired to work for specific departments and projects to assist full-time employees. The program was formalized, in part, as a response to increased workloads and decreased workforce during the latest economic downturn.

The county designated funding for interns to supplement their current workforce and to alleviate workload pressure. As part of the program, students work with departments that align with their career and educational goals, and departments gain additional human capital and capacity. And, there is an additional benefit: future members of the workforce have a positive experience with public service and the county becomes an employer of choice for students and millennials.

Within the first three years of the program’s official start, approximately 90 students from across the country interned across 15 departments. Today, interns are actively involved in the work of their departments, completing tasks that complement their interests and educational goals. Because interns are given the opportunity to work on meaningful projects and tasks, after the first three years of the program’s inception, program alumni applied for 68 positions with Henrico County.

Henrico County's internship programs have an additional benefit: future members of the workforce have a positive experience with public service and the county becomes an employer of choice for students and millennials.

The implementation of the Internship Program was not without challenges. It was initially difficult to appeal the program to department personnel because of concerns about finding suitable work for interns. In addition, relationships had to be established with schools, including high schools and universities, to help market the program to students. However, as the program grew and personnel shared the value of the interns’ contributions, department managers and schools were quick to participate.

In citing the success of the program, Becky Simulcik, assistant director of Human Resources, credits the creation of a full-time internship coordinator position that works with agencies and interns to make sure that both parties can get the most out of the program. The internship coordinator markets the program to department managers to show that interns serve as an asset to their team, not just another individual to manage. The coordinator works to ensure that both the intern and department have a mutually beneficial experience. Ms. Simulcik also points to Mr. John Vithoulkas’s, county manager, involvement and support of the program as a reason for its success. By having the county manager advocate for the program’s efficacy in front of the Board and agencies, the county has been able to develop the program successfully.

Takeaways

To improve the recruitment of qualified candidates, counties could:

Harness candidates’ drive for public service

Harness candidates’ drive for public service. Counties are the governments closest to the people. Focusing on this unique aspect in the recruitment process differentiates counties from other employers.

Offer an inside look

Offer an inside look at the value of working for county governments to create interest among younger job-seekers, such as through internship programs or recruitment videos.

Solicit feedback from existing employees

Solicit feedback from existing employees. Having honest conversations about what worked in prior recruitments, as well as how to target specific groups, can help ensure that qualified candidates apply for vacancies.

Retention

Counties must brainstorm methods to combat high millennial turnover – 21% in 2016.

Like other employers, county governments must contend with staff turnover. When the economy is strong, employees may find work with other employers who are not only hiring, but offering higher pay and benefits. The economic recovery is widespread, with low unemployment rates across the country (see Map 4). According to the Center for State and Local Government Excellence, state and local government human resources directors stated that the total number of resignations in their organization was 40 percent higher in 2016 than in 2014 and that retirement levels were 54 percent higher for the same period.11

Another concern for county managers is engaging with millennial workers. In 2016, 21 percent of millennials changed jobs within a year — compared to just 7 percent of non-millennials — and more than half reported that they do not feel engaged with their employer.12 Of larger concern to counties is the high cost of millennials’ turnover to employers and the national economy — $30.5 billion a year.13

40% higher number of resignations in state and local governments in 2016 relative to 2014

There are several misconceptions about the millennial generation. For instance, millennials and non-millennials alike value making a positive difference in the world through their job, receiving appropriate and competitive compensation and having a healthy work-life balance at the same levels.14 Additionally, the three top career priorities for millennials include teamwork, appreciation and support for their contributions and having flexibility in their schedule.15 And more tellingly, 90 percent of millennials would stay with an employer for the next 10 years if they received annual raises and upward mobility.16 Yet, many counties have also found ways to retain a diverse workforce through innovative solutions.

Map 2: Labor Force Unemployment Rate, 2017

County Explorer

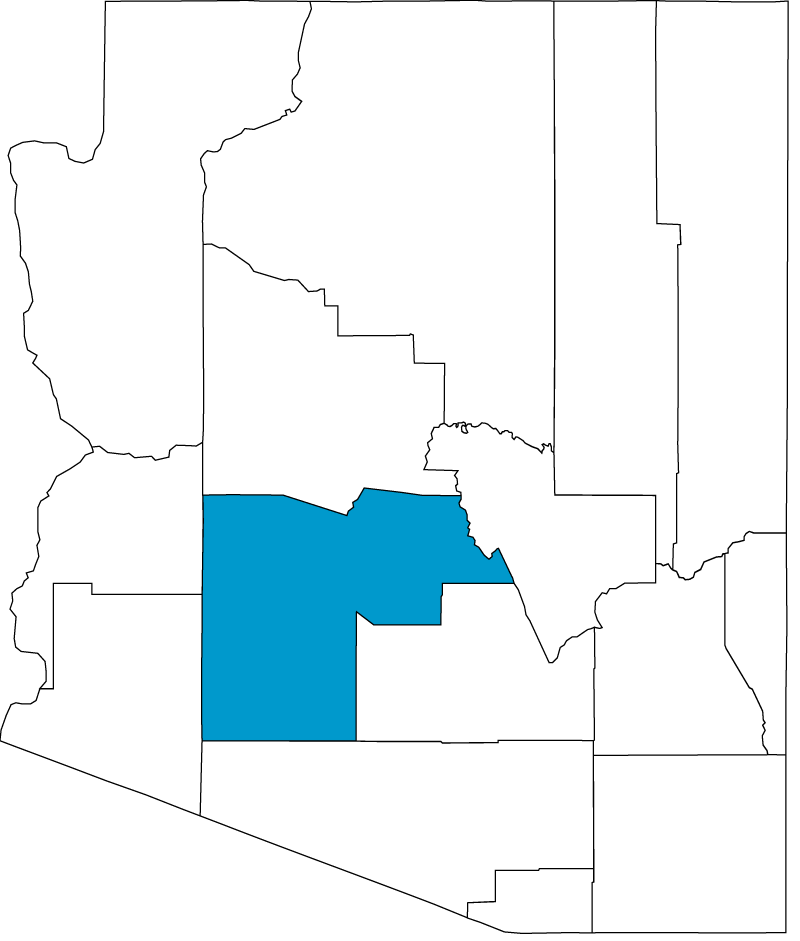

Maricopa County, Ariz.

2015 Population: 4,167,947 2015 Workforce: 13,200 Interviewee: MaryEllen Shepard, Assistant County Manager

Note: County workforce represents the number of both full-time and part-time employees. Source: NACo County Explorer, explorer.naco.org

Maricopa County, with the lowest turnover rate in Arizona, offers student loan repayment as a benefit.

According to the Arizona Association of Counties’ Salary and Benefit Survey, Maricopa County has the lowest turnover rate of all county governments in Arizona.17 Constantly seeking to understand employees’ needs helps contribute to this result, according to MaryEllen Sheppard, assistant county manager for Maricopa County. She adds that departments have prioritized determining what is important to their employees and have found ways to make Maricopa County an attractive place to work long-term. For example, employees may prefer a flexible schedule that allows them to come in later so they can drop their kids off at school or leave early to watch their kids’ sports games. In some situations, something as small as a relaxed dress code can improve morale. These changes do not place a strain on the county’s budget, but can result in savings with a reduced turnover.

The county government faces stiff competition for qualified employees from the large cities located within the county. As the nation’s economy has improved, Maricopa saw employees leave to work with other employers that offered more generous compensation packages. To compete, the county offers small annual pay-for-performance increases that have had a position impact on retention. Maricopa believes that employees who are committed public servants generally stay if their compensation remains relatively competitive. By recognizing the value of public service and the importance of rewarding performance, the county has been able to adjust to their priorities more efficiently.

As millennials continue to enter Maricopa County’s workforce, other work-life issues take priority. The nationwide average amount of student loan debt rose 56 percent from 2004 to 2014.18 In response to the financial strain millennials feel, the county helps its employees with student loan debt. For example, utilizing data that tracks how long attorneys typically stay with the county, Maricopa instituted a loan repayment schedule for attorney student loan debt. This plan incentivizes attorneys to stay with the county for several years. As a result, the county does not lose these highly skilled and trained workers, nor the institutional knowledge they have gained.

By identifying and working with employees’ values and priorities, Maricopa County has found solutions with minimal impacts on overall budgets.

Like many counties throughout the country, Maricopa cannot always provide competitive market wages for highly skilled employees or find additional funds for raises quickly enough if employees find higher paying jobs elsewhere. However, the county’s Board of Supervisors made a change permitting departments to offer a retention and recruitment salary advance. If Maricopa County departments can demonstrate that losing a critical employee to another employer would have a negative impact on operations (either through loss of knowledge, by having to search and hire another employee, etc.), that department, with the concurrence of Human Resources, has the authority to offer a salary adjustment to retain them. However, departments must have the budget to cover the salary raise. This allows the county to have flexibility in retaining highly valued or hard to replace employees

In Maricopa County, and in other county governments, retaining employees can be difficult in an environment of limited funding. However, by identifying and working with employees’ values and priorities, counties have found solutions with minimal impacts on overall budgets.

Map 3: Millennial Population, 2017

County Explorer

Takeaways

To retain a strong workforce, counties could:

Listen to employees

Listen to employees. Engage employees on a regular basis to identify their priorities, which may change with time, age and personnel circumstances. Employees may value non-monetary benefits, such as a more flexible work schedule, or non-traditional benefits, such as student loan repayment assistance.

Cater to employees’ priorities

Cater to employees’ priorities. Adapting to the employees’ needs may lead to a lower turnover rate.

Stay flexible

Stay flexible. Employees must often decide quickly when presented with a new job offer. Counties should be ready and prepared to offer competing wages and benefits in the event an employee is considering a move.

Retirement

Succession planning helps counties prevent the loss of institutional knowledge.

Retirement is another issue for employers across all sectors. Monthly, over a quarter-million employees in the United States turn 65.19 The number of baby boomers that retired grew from 10 percent in 2010 to 17 percent in 2016, creating the term “silver tsunami,” which is used colloquially to describe the effect of the country’s aging population.20 The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that while the U.S. workforce will grow through 2022, the overall labor force participation rate will decrease as more workers retire over time.21

This growth creates a conundrum for county governments that have significant numbers of their employees retiring or close to retirement. In general, governments tend to have larger shares of these employees than the private sector.22 As workers retire, they take valuable institutional knowledge with them and may leave departments short-staffed until their replacement is found, often a costly process. The Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) estimates that the average cost to fill a position is approximately $4,100 and can take 42 days or longer.23 Further, only 34 percent of companies have a succession plan in place for their workforces.24 Senior management and other executives were more likely to have a succession plan, thereby reducing the disruption a retirement at these higher levels may cause.

54% higher number of retirements in state and local governments in 2016 relative to 2014

All county governments face the workforce issues associated with retirement. However, some counties have found ways to ensure that they are prepared when their long-tenured employees retire.

Map 4: Percent Population 65 Years and Older, 2017

County Explorer

Oneida County, Wisc.

2015 Population: 35,567 2015 Workforce: 271 Interviewee: Lisa Charbarneau, Human Resources Director, Oneida County, Wisc.

Note: County workforce represents the number of both full-time and part-time employees. Source: NACo County Explorer, explorer.naco.org

With advanced notice, counties can use future retirees as on the job trainers for their replacements.

Oneida County is a rural county in northern Wisconsin. Finding replacements for retiring employees is difficult given the smaller population size. In 2011, Wisconsin passed Act 10, which impacted public service employees that belonged to a union, including those in Oneida County’s workforce. Before the legislation was passed, employees could retire at age 55, and, if they had worked for the county for 20 years, could keep their health insurance until they became eligible for Medicare. With the passage of Act 10, this health insurance benefit decreased for existing employees so that they would only have seven years of coverage following retirement. The decreasing health insurance benefit also included an additional payment into qualified employees’ Health Reimbursement Accounts to fill the gap of reducing coverage from 20 to seven years. This payment expired at the end of 2016 causing many workers to retire from the county when they were still eligible to receive the payment.

In response to this unexpected turnover, the county took swift action in to dealing with potential retirements and succession planning, as explained by Human Resources Director Lisa Charbarneau. The first was to better utilize the current workforce by ensuring that employees on a specific career path had the proper skill set to backfill retired positions. By examining which employees had potential to rise to a specific position, the County could then create a "checklist" of skills and education for those workers to attain over the next several years.

“Oneida County utilizes our existing workforce to supplement the workload of pending retirements to ensure a smooth transition”.

– Lisa Charbarneau, Oneida County, Wisc.

Another approach Oneida County employs is to overlap employees for a position that will soon be vacant. The county mandates at least one-month notice for retirement, but department heads often give close to a year’s notice. When an employee announces their retirement, their replacement is hired while the incumbent is still employed by the county. The new employee thus has ample on-the-job training and the department experiences a smooth transition with little impact on overall operations.

Ms. Charbarneau estimates that there are 30 new employees hired annually throughout the county and approximately two-thirds take advantage of the overlap system. Departments may use contingency funds for the new hires, as opposed to their own budget, or the county may use non-departmental funds. Though this system is widely used, it is not without challenges. Other counties surrounding Oneida also face a retiring workforce. Therefore, when specialized and specific job titles become vacant within several counties the competition is tight to find a qualified candidate, but fortunately the notice system in place for retiring employees provides ample time for the transition.

Franklin County, Ohio

2015 Population: 1,251,722 2015 Workforce: 6,435 Interviewee: Sue Hamilton, Assistant Director of Human Resources, Franklin County, Ohio

Note: County workforce represents the number of both full-time and part-time employees. Source: NACo County Explorer, explorer.naco.org

By outsourcing positions, Franklin County, Ohio stores institutional knowledge in a company, not a person.

Some counties must manage with delayed retirements that come with their own set of challenges. According to Sue Hamilton, assistant director of Human Resources at Franklin County, Ohio, employees are not retiring when they are eligible to do so at a certain age or upon the attainment of a certain number of years of service. Rather, employees are working past these milestones, creating a series of operational challenges.

For example, payroll costs and self-insured health expenses rise. Further, these employees have higher vacation accruals and often more health issues, resulting in more time away from the office. In some situations, there is a reluctance among longer tenured employees to take on operational improvements or new initiatives. To deal with the unpredictability of retirement, as well as to retain the institutional knowledge or retiring employees, the county has undertaken a multipronged approach.

Part of this approach includes a basic standard for any workplace: making sure the retiring employee doesn't depart before creating a detailed report of duties and increasing the amount of communication needed to update managers on project updates. When a retiring employee leaves, their manager is up-to-date on ongoing projects and resources and can share that with their replacement.

Adding to the first tactic, another way Franklin County manages knowledge transferral also helps to increase existing employee skill sets. When a retiring Franklin County employee provides advance notice of an upcoming retirement, the county may temporarily assign another employee to that same position for on-the-job training. Departments are encouraged to start this transition process immediately by having the retiring employee cease day-to-day operational tasks and spend their time training their replacement, as well as documenting processes, contacts and the status of outstanding items.

To deal with the unpredictability of retirement, as well as to retain the institutional knowledge of retiring employees, Franklin County takes a multipronged approach.

Another approach Franklin County has taken is conducting operational reviews to determine whether opportunities exist when a retirement occurs. For example, if an employee with a specific skill set retires, the county may consider outsourcing the position’s responsibilities to an outside vendor rather than filling the position internally. When feasible, this option can help alleviate the loss of institutional knowledge as positions turn over. Outside companies can draw upon the talents of all their employees to problem solve or service the county contract, whereas the county may only have one person with the know-how to troubleshoot an issue. That way, the institutional knowledge is shared within a company, rather than with an individual, which promotes continuity of operations.

Takeaways

To prepare for the retirement of employees, counties could:

Plan ahead

Plan ahead. In any organization, retirement is inevitable. Preparing for these retirements is essential, such as through overlapping the transition of the retiring employee with the hiring of their replacement, documenting work processes and conducting operational reviews.

Knowledge transfer and succession planning

Think outside the box when it comes to knowledge transfer and succession planning. For example, keep institutional knowledge within a position or outside company rather than with an individual employee. Or, train employees in such a way that they can temporarily step into a vacant position until a replacement is found. Having a multi-pronged approach allows

Conclusion

Counties have successfully met the challenges of the workforce in recruitment, retention and retirement with innovative ideas.

Managing a county government’s workforce, including the recruitment, retention and retirement of employees, presents unique challenges and opportunities. Recruiting a qualified workforce, including millennials, may be a challenge due to improved economic conditions and negative connotations of public sector employment. In addition, once new employees are on board, it can be difficult to compete with other employers that may offer stronger compensation packages. Due to an aging labor force, counties are rapidly losing institutional knowledge and struggling to backfill these critical positions. However, counties can manage these uncertainties by taking an innovative approach to re-energize their workforce, including: demonstrating the public service benefits of working in county government to younger workers, finding out what new and existing employees value in the work place and planning in advance for retirements.

Endnotes

1 Alicia H. Munnell, Jean-Pierre Aubry, Josh Hurwitz and Laura Quinby, “Comparing Compensation: State-Local Versus Private Sector Workers”, Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, September 2011, available at http://crr.bc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/ slp_20-508.pdf.

2 Kathy Robertson, “How Long Do Workers Stay in Jobs?”, Sacramento Business Journal, December 27, 2012, available at http://www. bizjournals.com/sacramento/news/2012/12/27/how-long-do-americans-stay-in-jobs.html.

3 Richard Fry, “Millennials Overtake Baby Boomers as America’s Largest Generation”, Pew Research Center, April 25, 2016, available at http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/04/25/millennials-overtake-baby-boomers/.

4 “Survey Findings State and Local Government Workforce: 2016 Trends”, Center for State and Local Government Excellence, May 2016, available at http://slge.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/State-and-Local-Government-Workforce-2016-Trends.pdf.

5 Alicia H. Munnell, Jean-Pierre Aubry, Josh Hurwitz and Laura Quinby, “Comparing Compensation: State-Local Versus Private Sector Workers”, Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, September 2011, available at http://crr.bc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/ slp_20-508.pdf.

6 Rawn Shah, “Have You Got Millennial Expectations All Wrong?”, Forbes, September 25, 2014, available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/ rawnshah/2014/09/25/have-you-got-millennial-workforce-expectations-wrong/#7eb74ea7695e.

7 Richard Fry, “Millennials Surpass Gen Xers as the Largest Generation in U.S. Labor Force”, Pew Research Center, May 22, 2015, available at http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/05/11/millennials-surpass-gen-xers-as-the-largest-generation-in-u-s-labor-force/. Graham Vyse, “Millennials Have Lots of Problems with Working Government Jobs”, Inside Sources, August 11, 2016, available at http://www. insidesources.com/millennial-government-jobs/.

8 Dr. Peter Viechnicki, “Understanding Millennials in Government”, Deloitte University Press, November 9, 2015, available at https:// dupress.deloitte.com/dup-us-en/industry/public-sector/millennials-in-government-federal-workforce.html.

9 Patricio G. Balona, “Volusia Deputies Union Complains of Staff Shortages, Low Pay”, June 6, 2017, available at http://www.news-journalonline.com/news/20170606/volusia-deputies-union-complains-of-staff-shortages-low-pay.

10 “Struggle Continues to Find Child Protection Workers”, KSTP, August 3, 2016, available at http://www.wdaz.com/news/ minnesota/4086131-struggle-continues-find-child-protection-workers.

11 “Survey Findings State and Local Government Workforce: 2016 Trends”, Center for State and Local Government Excellence, May 2016, available at http://slge.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/State-and-Local-Government-Workforce-2016-Trends.pdf.

12 Amy Adkins, “Millennials; The Job-Hopping Generation”, Gallup, May 12, 2016, available at http://www.gallup.com/ businessjournal/191459/millennials-job-hopping-generation.aspx.

13 Ibid.

14 Rawn Shah, “Have You Got Millennial Expectations All Wrong?”, Forbes, September 25, 2014, available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/ rawnshah/2014/09/25/have-you-got-millennial-workforce-expectations-wrong/#7eb74ea7695e.

15 Sarah Gantz, “Millennials Under-Represented in Federal Workforce as a Retirement Boom Looms”, The Baltimore Sun, October 28, 2016, available at http://www.baltimoresun.com/business/bs-bz-millennial-workers-20161028-story.html.

16 Maggie Overfelt, “Millennial Employees Are A Lot More Loyal than Their Job-Hopping Stereotype”, CNBC, May 10, 2017, available at http://www.cnbc.com/2017/05/10/90-of-millennials-will-stay-in-a-job-for-10-years-if-two-needs-met.html.

17 “2017 Arizona County Government Salary and Benefit Survey”, Arizona Association of Counties, 2017, available at http://www.azcounties.org/ DocumentCenter/View/1223.

18 “Student Debt and the Class of 2014”, The Institute for College Access & Success, October 2015, available at http://ticas.org/sites/default/files/pdf/ classof2014_embargoed.pdf.

19 Ben Casselman, “What Baby Boomers’ Retirement Means for the U.S. Economy”, FiveThirtyEight, May 7, 2014, available at https://fivethirtyeight. com/features/what-baby-boomers-retirement-means-for-the-u-s-economy/.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 “Employed Persons by Detailed Industry and Age”, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, February 8, 2017, available at https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat18b. htm.

23 “Average Cost-Per-Hire for Companies is $4,129, SHRM Survey Finds”, Society for Human Resource Management”, August 3, 2016, available at https://www.shrm.org/about-shrm/press-room/press-releases/pages/human-capital-benchmarking-report.aspx.

24 Ibid.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Brandy Winterbottom- Whitney (San Diego County, Calif.), Becky Simulcik (Henrico County, Va.), MaryEllen Sheppard (Maricopa County, Ariz.), Lisa Charbarneau (Oneida County, Wisc.) and Sue Hamilton (Franklin County, Ohio) for providing essential information and comments for the study. Without them, this project would not have been possible. Within the National Association of Counties, the author would like to thank Emilia Istrate, Christina Iskandar, Jonathan Harris, David Jackson, Carlos Greene and Sanah Baig for their helpful comments and contributions. Big thanks go to Anna Martin who provided significant input into the study. The author also expresses his appreciation to his Public Affairs colleagues for the graphic design and the website of the report.

About the Counties Futures Lab

The NACo Counties Futures Lab brings together leading national experts to examine and forecast the trends, innovations and promises of county government with an eye toward positioning America’s county leaders for success. Focusing primarily on pressing county governance and management issues — and grounded in analytics, data and knowledge sharing — the Lab delivers research studies, reports and other actionable intelligence to a variety of venues in collaboration with corporate, academic and philanthropic thought leaders to promote the county government of the future.