Election security: Building trust at the ballot box

Author

Dr. Alan Shark

Upcoming Events

Related News

Key Takeaways

With National Cybersecurity Awareness Month upon us and only weeks away from the 2018 elections, county officials can’t help but wonder: “How secure is our election system?” And let’s face it, there’s far more at stake than simply deciding upon a winning candidate — trust in government is behind every ballot.

As widely reported, we know that cybercriminals tampered with the 2016 election. This has led to discussions about how to secure voting in districts across the country, especially as they increasingly transition to digital processes. Recognizing that voting procedures are set by each state, there is no blanket regulation that would improve upon voter security throughout the nation.

Learn More

This year, the Election Assistance Commission handed out $380 million dollars targeted for states to use as they see fit. Most will agree that this initial funding didn’t come close to addressing the real needs of local governments — especially counties, which do the heavy lifting when it comes to local elections.

There are more than 8,000 jurisdictions across the country responsible for the administration of elections.

Cyberattacks have dramatically escalated in the past 2.5 years and have become more sophisticated and harder to detect and not limited to elections either. Since elections are entwined with trust, this is what is getting everyone’s attention these days.

There is some good news to report, and that is the availability and publication of the Handbook for Elections Infrastructure Security published by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). funded by the Center for Internet Security (CIS).

This is a great resource that every public official should download and read (it’s free) and the list of contributors and reviewers is reassuring.

The primary goal of this handbook is to help improve the security of elections infrastructure as soon as possible, and ideally in advance of the 2018 elections, and establish a set of best practices that, with continual updates, support elections infrastructure security into the future.

The folks at CIS expect many elections systems will already incorporate the majority of these mitigations, allowing those jurisdictions to demonstrate a strong baseline. In that case, the handbook can assist in prioritizing for continual improvement and evolution.

While there is always the temptation to look for easy templates and solutions, the handbook does not recommend any single approach to managing election systems or developing and deploying any particular election systems technology.

Instead it recommends that election jurisdictions tailor their voting processes and systems to the needs of their voters and jurisdictional laws and requirements.

Developing a risk assessment is the best place to start. Just a few years ago, most strategies were aimed at eliminating any cyberattack through hardware and software solution defenses. Today no technology professional can guarantee 100 percent safety and immunity from cyberattacks and intrusions. We have come to accept the new reality that we can only mitigate risk and develop remediation strategies if and when something happens. As the CIS Handbook points out, it all starts with a top-level assessment of vulnerabilities and potential consequences to the elections systems infrastructure and by identifying network connectivity — devices or systems that work with other devices or systems to achieve their objectives — as the major potential vulnerability.

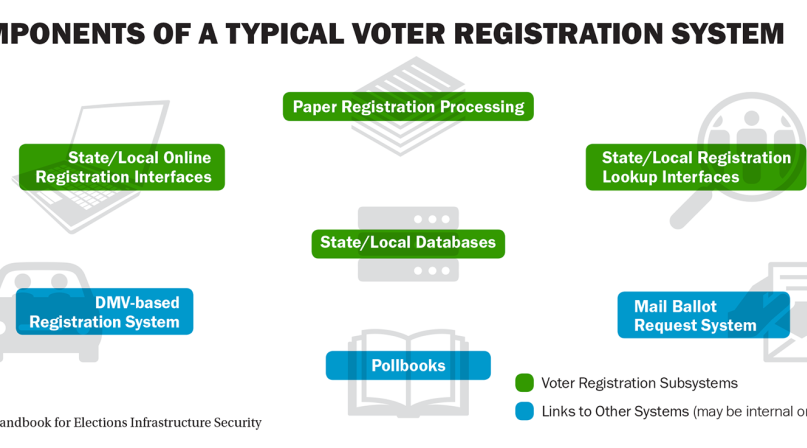

The reason is simple: Given an adversary with sufficient time and resources, systems that can be accessed via a network cannot be fully protected against compromise. There are ways to improve the security of network connected systems with additional controls, but the inherent complexity of network connectivity results in significant residual vulnerabilities. As shown, election systems are linked one way or another to other systems and it is where the transfer of information can also lead to points of extra risk.

Of course, many counties are dealing with outdated or unproven technologies. To make matters worse, they lack the technical expertise or lack the resources to bring in outside experts. Such obstacles, while not to be ignored, should not be offered as a blanket excuse for not acting with the resources you do have access to. Aside from the obvious network integrity and communications issues, the handbook offers some useful insights into the following:

Eligibility for an individual to register to vote;

Voter identity verification, unless specifically about the accuracy and availability of voter registration rolls;

Security of campaigns or campaign information systems; and

The accuracy of information about candidates or issues, including those conveyed using social media.

For election systems, this involves establishing trust in users, devices, software and processes. Many systems are “composed” or built up from a variety of commercial and purpose-built parts, device and software connected via processes and user actions. The results in security decisions about trust are made across many components and brought together at a system level. In other cases, key election system components or services functions are contracted out. This does not change the security responsibility for decision-makers, but forces them to think about how the desired security properties can be specified in contract language and service specifications, rather than implemented directly. The last of the three sections focus on:

1. A set of critical risk-mitigating activities from which all organizations can benefit,

2. Recommendations for best practices in contracting for IT services, and

3. A set of best practices in the form of recommendations and controls for network connected and indirectly connected devices, as well as for transmission of information.

The handbook should be required reading for all election officials and can serve as the basis for in-house training or at the very least meaningful discussion among the various stakeholders.

Better yet, the CIS created the Elections Infrastructure-ISAC and membership is free. Once signed up, you will receive timely information about what is happening in localities across the nation.

Let’s vote for being better informed and active. Everyone will benefit in the midterm elections.

Attachments