Election officials: ‘Flatten the curve,’ avoid backups amidst pandemic

Robyn Stallworth Poquette compares election preparations to planning 100 weddings on the same day.

“It’s as if nobody has RSVPed and you have to make dietary adjustments for all your guests…it’s really difficult,” the Yuma County, Ariz. recorder said, fresh off a primary election that essentially served as a rehearsal for the general election. In addition to being a presidential swing state, Arizona will see a U.S. Senate race pitting the first woman combat pilot against an astronaut. Poquette expects turnout to be massive, dwarfing her primary that featured no local races.

Add the COVID-19 pandemic to that and suddenly every family has a relative whose musical reputation outstretches their talent, but not their mother’s confidence about performing at the reception. Mixed with competing rhetoric questioning ballot security and integrity, and now the brides and grooms want their cats to serve as ring bearers.

Learn More

Counties and the 2020 Election: Ask the Experts - Sept. 22, 2 p.m. Eastern

The COVID-19 pandemic has fundamentally altered the landscape of the 2020 election cycle. America’s counties traditionally administer and fund elections at the local level, overseeing more than 109,000 polling places and coordinating more than 694,000 poll workers every two years. Faced with both new election-related challenges due to COVID-19, and concerns over cybersecurity, foreign influence, and aging technology, election administrators across the country have worked tirelessly to finalize preparations needed to conduct a free and fair election. Hear from federal and local elections officials about how they are working to ensure a safe, fair and secure election this fall.

- Ben Hovland, Chairman, U.S. Election Assistance Commission (opening remarks)

- Don Palmer, Commissioner, U.S. Election Assistance Commission (opening remarks)

- Ricky Hatch, Clerk/Auditor, Weber County, Utah

- Batina Dodge, Clerk, Scotland County, Mo.

- Alysoun McLaughlin, Deputy Elections Director, Montgomery County, Md.

- Michael Vu, Registrar of Voters, San Diego County, Calif.

- Matthew Weil, Director for the Elections Project, Bipartisan Policy Center (moderator)

To register for the session, click here.

Election Assistance Commission releases new resources to support local elections officials

When presented with those added layers to the chaos, Poquette said that sounded right.

“Election management is out of sight, out of mind for most people,” Poquette said. “People are generally unaware of the expensive preparation that everything takes.”

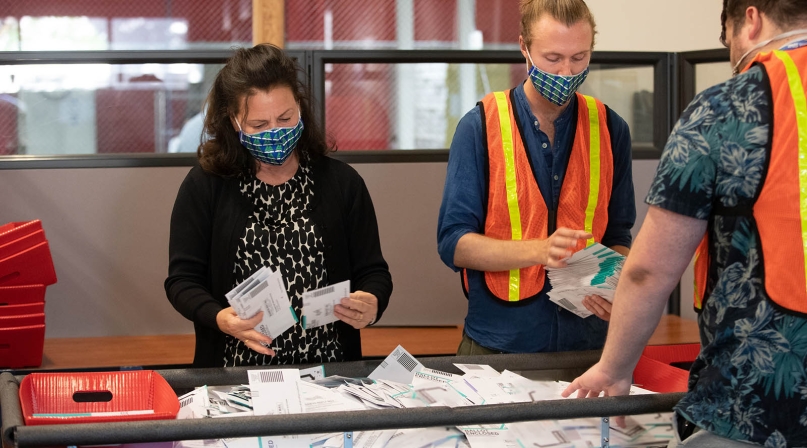

On the heels of counties enacting policies to “flatten the curve” and keep COVID-19 patients from overwhelming hospitals, county election workers are following the same playbook to help them through a general election that is projected to see a massive increase in voting by mail to avoid crowds, and the coronavirus, at polling places.

For Yuma’s much larger Arizona county cousin, Maricopa County, Ariz., the fourth largest in the country, a failure to do that could be catastrophic, so Government Relations Director Tonia Tunnell stresses making voting early as easy as possible.

“If your state allows no-excuse absentee voting or COVID can be an acceptable excuse, mail ballot request forms to all active voters,” she said. “Just do it.”

That counts for 28 states and the District of Columbia, plus Nevada, which will mail absentee ballots, not absentee ballot applications, to all registered voters. New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy (D) recently announced plans to mimic Nevada. Five states conduct all-mail elections.

The place to be

That means 15 states, so far, will require excuses to acquire an absentee ballot or else voters will have to show up in person, and management of polling places will get a lot of scrutiny in light of coronavirus physical distancing requirements.

Though Arizona allows no-excuse absentee ballots, Maricopa County moved to meet those demands with voting centers, which frees voters from being tied to their precinct. In the primary, instead of 1,142 voting locations, the county staffed 99 much larger voting centers, which opened 27 days before the election ended.

“We were moving toward a voting center model, but COVID pushed us all the way there,” she said, “The biggest factor that made it happen was shopping centers.”

Contracting with shopping centers gave the county much larger spaces to work with and brought customers near the stores.

“The vast majority of those voting centers had at least 12 check-in stations,” Tunnell said. “You can’t do that in a school library. We had all the room we needed to spread out.”

Even though Nevada is mailing out ballots to all registered voters, Eureka County will maintain ballot collection locations at the north and south end of the small rural county.

“We had a lot of pushback in the primary, we have a lot of voters who would rather do it in person,” said Mike Nunn, deputy clerk recorder. “They’re skeptical, they want to do things the way they’ve always done them, so we’re giving them that option.”

Playing host to polling places will require a significant amount of personal protective equipment and cleaning supplies, all expenses Tunnell said could be covered by coronavirus relief aid.

“Every poll worker is going to have a mask, shield and gloves,” she said. “We’ll have masks for everyone in case they forgot one, we’ll have single-use pens for the ballots. We’ll need disinfecting wipes, tape to mark spacing on the ground…these are all new expenses because of COVID, and COVID money should pay for it. They add up.

“These are expenses that we wouldn’t have had in previous years — going from a school library that was free to a commercial location that gives us the space to do social distancing, it’s going to cost the election department money, so we need Congress to pitch in and help us with that,” she said.

Poll positions

Tunnell said some poll workers manned their voting centers for 27 straight days in the primary, with many more working 14 days. Recruiting that workforce is crucial, and she suggested that current conditions could require having a reserve corps that could be half of the normal complement.

“People are going to back out, they might get scared, they might get talked out of it, or they could get sick,” she said. “You’ll have to replace backups, too, so you can’t get complacent.”

Joyce McKinley has a great recruiter in Centre County, Pa., where she is director of elections.

“We have a teacher at Bellefonte High School who does half the training for poll workers from the school,” she said. “We send them in groups of two to different precincts.”

Some alumni come home from college to work the polls, and McKinley said that teacher came up with 75 different poll workers from his classes in 2016.

“I don’t know what we’ll do when he retires,” she said.

Centre County includes Penn State University, where McKinley has combined all of the precincts for ease of voting in the student union.

Tunnell said civic duty pay measures could sweeten the deal for poll workers, who can collect the pay on top of their salary.

Poll workers end up being the public face of election officials.

“They try to really garner the trust of our community in a county like ours where we want to make voters feel safe and secure going to the poll and receiving their early ballot in a way they feel confident that their vote counts,” Poquette said.

“Staff are having communications with frustrated voters, voters who are hearing different rhetoric from neighbors on security. That’s not easy.”

Mailing it in

Clerk Polly Olson saw mail-in ballots boost turnout in Deuel County, Nebraska’s primary, and she is sure that trend will continue when the races add more gravity.

“In a primary election without a lot of local issues, we don’t usually have a lot of turnout but we saw an increase because the secretary of state helped us in sending out mail-in ballots,” Olson said.

McKinley is expecting as many as 44,000 absentee ballot requests in the general election, twice what the primary drew. Centre County is considering contracting with a mailing service to distribute the ballots.

Knowing who is getting the ballots is the first step toward ensuring a vote’s validity.

“A successful and secure mail vote program has to start with having really good voter registration lists,” Tunnell said. “You have to be very vigilant about the national Voting Rights Act and how you keep your voter list clean. Even before we mail ballots out, we compare our list to the national change of address (registry).

“We know every ballot is going to a real person who is living.”

In Yuma County, that work will start the second week of September, when Poquette’s temporary workers start auditing their address lists before the ballots go out Oct. 7.

A spate of unsolicited, prefilled absentee ballots from the Center for Voter Information is making counties’ jobs harder to conduct business by mail. Fairfax County, Va. residents received mailers with a return address to the city of Fairfax. Though the city and county are cooperating to make sure the applications reach the right office, Fairfax County General Registrar Gary Scott said the mailing is also confusing voters who have previously submitted absentee ballot applications themselves. These voters are worried that their applications were not received, leading them to think they need to apply again.

The same problem has surfaced with Roanoke, Richmond and Franklin counties and their namesake cities, though the latter two are farther apart than Fairfax and Roanoke counties are from their respective cities.

In response to a similar problem in North Carolina, the Legislature there passed a law prohibiting pre-filled absentee ballot request forms.

Get them to sign on the line which is dotted

To vote absentee in Scotland County, Mo., you’ll need a notary. Clerk Batina Dodge said it isn’t hard to find one, but it’s an extra layer of security.

“The virus hasn’t been a big concern here, so I don’t think we’ll see a big demand for absentee ballots,” she said.

Her small office has talked about contingencies if things change and they get inundated with ballot requests, but even then, they’ll have an idea how many to plan to process.

“I don’t know what the situation will be the closer we get to November,” she said.

The proliferation of mail ballot access has been met by skepticism, including by President Trump, himself a mail voter in Florida. Weber County, Utah Clerk Auditor Ricky Hatch said Utah’s all-mail election, now in its third year, and Weber County’s seven-year program has received bipartisan support in the county and an endorsement from Republican gubernatorial candidate Spencer Cox.

“Vote by mail has been a good process for Utah, there are a lot of controls and you can trust it,” Hatch said.

When he hears questions about Weber County’s mail ballot security, Hatch points to the county’s successes and security procedures.

“It’s usually people who haven’t been paying attention to that in the past or pipe up on social media repeating what they’ve heard nationally,” Hatch said. Signature verification is the crucial step in verifying ballots, which election judges, trained in handwriting analysis, do with each ballot that comes in, comparing the signature to up to five on record from different government documents. If a ballot fails, then it is routed to a full team of election staffers. If it doesn’t pass muster, they contact the voter.

“It’s getting better because the quality of signatures we have on file has increased,” Hatch said, “The failure rate is much lower than it used to be.”

We want it that way

State governments are still taking action that could affect how counties administer their elections, and it’s crucial to make counties’ voices heard in the process. Hatch is worried that the Utah Legislature’s special session could impose new rules, like when it outlawed in-person voting options during the primary.

“We asked them then to let us choose,” Hatch said. “They said you could choose between mail or a voter not leaving their car to drop off their ballot and the county assumes all the liability.

“We may get something similar.”

Hatch doesn’t mince words.

“Let us run our elections the way we know,” he said. “We know our public and our poll workers. We’ve handled difficult situations like this before and we’ve done great, but we’d like to mail out our ballots a little earlier than before to give people and the post office extra time to process everything.”

Tunnell said unilateral action without input from the people who put on elections is one of the fastest ways to lose the confidence of the voting public.

“States, please talk to us before you make statewide decisions,” she said. “Counties know what their culture is.”

Too many changes, like sudden changes to state-wide mail ballots in Nevada, could throw people for a loop. Eureka County’s staff struggled to keep up with the changes so they could be a trusted authority to the public.

“They need reassurance that their vote will count, and it won’t be subject to fraud any more than in a regular election,” Nunn said.

It’s a situation where even though a national election is a composite of 3,069 smaller units, scaling doesn’t necessarily mean better results.

“Being as small as we are is beneficial to the community,” Nunn said. “Everybody knows everybody. We’re here in case people have questions. We stay on top of requests from the public.”

Attachments

Related News

2024 Clearinghouse Awards: U.S. Election Assistance Commission recognizes county excellence in election administration

The U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC) announced the winners of its 2024 Clearinghouse awards, recognizing 32 counties for their election administration practices during the 2024 election cycle.

County Countdown – April 7, 2025

Every other week, NACo's County Countdown reviews top federal policy advocacy items with an eye towards counties and the intergovernmental partnership. This week features a budget reconciliation update, HHS restructuring and more.