Building Wildfire Resilience: A Land Use Toolbox for County Leaders

Upcoming Events

Related News

Wildfires have been increasing in size, duration and destruction to communities over the past 20 years, reaching crisis-level conditions today across the nation but primarily in the West. In 2015, 2017 and 2020, more than 10 million acres burned nationwide – an area more than six times the size of Delaware.[1] Today, nearly a quarter of the contiguous United States is at moderate to very high risk of wildfire. Unfortunately, “fire seasons” have all too often been transformed into entire “fire years,” requiring year-round workforce for fire suppression, recovery and planning for future wildfires.

Wildfire risk has increased to its current crisis level due to a series of factors, such as accumulating fuels from forest management practices and expanded growth into fire-prone forested landscapes referred to as the wildland-urban interface (WUI).

Wildland fire occurs naturally in almost all vegetated ecosystems across North America, to varying degrees of frequency and intensity and generally is considered beneficial to most ecosystems. Before European settlement, fire was used by Native Americans as a tool to support sustainable forests, agricultural lands and wildfire hunting habitats. Frequent wildland fires kept forest landscapes open and healthy from the longleaf pine forests of the South to the ponderosa pine woodlands of the West. Historically, wildland fires in many landscapes were cool and low to the ground, rarely entering treetop canopies and burning entire forests.

In the early 20th century, a rapidly growing United States that relied on timber for economic and industrial development began to view forest fires as an economic threat. As a result, using fire was no longer considered an optimal land management practice. By 1935, the U.S. Forest Service adopted the “10 a.m. policy,” which sought to suppress all wildland fire by 10 a.m. the following morning. This national fire exclusion approach led to over a century of vegetation accumulation, producing the fuel that feeds the larger and more intense wildland fires we see today.

Wildfire poses considerable risk to lives, livelihoods and homes where the built environment meets and mixes with the natural environment. Despite risk, the WUI has grown immensely since the 1960s as Americans continue to seek open spaces, scenic beauty and access to recreation. Presently, one in three homes in the U.S. is located within the WUI. Population growth paired with over a century of fuel accumulation compounds to increase both the risk of wildfire and the damage they produce. In the 2000s, wildfires were destroying hundreds of homes and structures each year; by the 2010s that number was in the thousands.

As county leaders across the nation grapple with wildfire risk and impact, expert practitioners and local leaders have developed a variety of tools and strategies to help mitigate wildfire impacts on lives, property and communities. Many of these approaches are best executed at the local level as counties are uniquely positioned to mitigate wildfire through effective land use planning, land management and community engagement.

Overview of Key Terms

Wildland Fire: Any non-structure fire that occurs in vegetation and natural fuels, including wildfires and prescribed burns.

Wildfire: Any unplanned wildland fire that results in negative impact to life, structures, and infrastructure.

Fuel: Any substance that will ignite and combust. As relates to wildfire, fuels can be either wildland fuels (e.g., vegetation) or built fuels (e.g., structures)

Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI): Pronounced woo-eee, the WUI is a geographic area where the natural environment meets and intermixes with the built environment, allowing for the ignition and spread of fire through both wildland fuels and built fuels.

Mitigation: The act of modifying the environment or human behavior to reduce potential adverse impacts from a natural hazard.

Fire-adapted community: A human community consisting of informed and prepared citizens collaboratively planning and acting to safely coexist with wildland fire.

Structure Ignition Zone: The area surrounding a structure and any accessory structures, including all vegetation that contains potential ignition sources and fuels.

Defensible Space: A buffer area surrounding a structure where flammable vegetation and other fuels can be modified and maintained to slow the spread of wildfire.

Fuel Treatment: Various techniques to reduce the amount of fuel

Forest Health: The resiliency of a forest and its ability to self-renew following drought, wildfire, disease or other disturbances.

I. National Cohesive Wildland Fire Strategy

The National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy (Cohesive Strategy) effort was first created through the Federal Land Assistance, Management, and Enhancement (FLAME) Act of 2009.

The Cohesive Strategy is a strategic framework that emphasizes collaboration among stakeholders and across landscapes, sometimes referred to as an All Hands, All Lands approach. A significant shift from the prior century’s policies of fire exclusion and rapid fire suppression, the Cohesive Strategy builds on a growing body of evidence to make meaningful reductions in risk and increase capacity to live with wildland fire. The Cohesive Strategy focuses on three central goals toward achieving its vision[2]:

GOAL 1: Resilient LandscapesLandscapes, regardless of jurisdictional boundaries, are resilient to fire, insect and disease disturbances GOAL 2: Fire Adapted CommunitiesHuman populations and communities are as prepared as possible to receive, respond to and recover from wildfire GOAL 3: Safe and Effective Wildfire ResponseAll jurisdictions participate in making and implementing safe, effective and risk-based management decisions |

The Wildland Fire Leadership Council (WFLC) is an intergovernmental committee of Federal, state, tribal, county and municipal government officials convened by the U.S. Secretaries of the Interior, Agriculture, Defense and Homeland Security. WFLC is dedicated to the consistent implementation of wildland fire policies and management activities, including the Cohesive Strategy. WLFC includes a county representative through the National Association of Counties to ensure the county perspective and input are actively included in the implementation of the Cohesive Strategy framework in counties across the nation.

As integral stakeholders and partners in the implementation of the Cohesive Strategy, counties have a transformative role and opportunity to help create Resilient Landscapes, build Fire Adapted Communities and foster a Safe, Effective Wildfire Response. While not an exhaustive resource, this toolbox is comprised of science-based approaches and key strategies available to educate, equip and empower counties to build wildfire resilience and protect residents and communities.

II. Community Planning

As with the national Cohesive Strategy, local and regional planning is an essential action for wildfire mitigation. Developed following a thorough public input process involving multiple stakeholders, local community plans provide analysis and specify future actions to achieve desired outcomes. Community and land use planning guides local decision-making concerning both the natural and built environment and helps shape growth and development.

Community engagement is important for ensuring the local vision and resulting plan reflect community interests and have the buy-in needed for successful implementation. This community engagement process also presents opportunities for wildfire education and building awareness that characterizes fire-adapted communities.

Because county authorities vary state-by-state, county strategies will vary according to state statutes that allow local planning and regulation efforts. A variety of planning options exist to support counties in setting strategic visions for mitigating wildfire risk and damage. Four key options are comprehensive plans, hazard mitigation plans, community wildfire protection plans and comprehensive economic development strategies.

Community Planning Options

|

Comprehensive Plans

Also referred to as General Plans or Master Plans, Comprehensive Plans are foundational local policy documents that guide long-term planning decisions for land use, growth and change for 20 to 30 years. Comprehensive Plans typically include an analysis of both existing conditions and future trends, while also citing goals and policies to implement a community’s vision for the future. Comprehensive Plans typically contain existing and future land use maps.

Comprehensive Plans provide an opportunity for counties to think strategically and spatially regarding how and where your county grows and develops. Incorporating wildfire risk and hazard analysis into these goals and decisions is one approach to mitigate wildfire damage and help build fire-adapted communities. For example, identifying the WUI and hazard areas, reviewing existing land-use in wildfire hazard areas and/or recommending strategic development standards within hazard areas all could be addressed in a comprehensive plan. Comprehensive Plans can also include topics and goals referencing local wildfire issues of housing, disaster preparedness and recovery, protection of natural resources and the role of fire on the landscape. Further, Comprehensive Plans often reference other related plans, such as the Community Wildfire Protection Plan (below).

Counties in Action

Larimer County, Colorado

- The 2019 Larimer County Comprehensive Plan is a policy document establishing a long-range framework for decision-making in the county. This plan identified 10 core themes, including the goal: ‘Building a More Resilient Future.’ Further, identified in the Terrain & Natural Hazards category of this plan are several priorities regarding wildfire mitigation, such as designing development to mitigate hazards; discouraging development in hazard areas or requiring long-term hazard mitigation; creating defensible space in hazard-prone areas; and evaluating, strengthening and complying with regulations in hazard areas.

- Learn more

Wasco County, Oregon

- The Wasco 2040 plan is a 30-year vision for land use planning in the county and was the result of three years of public and stakeholder engagement. Outlined in Wasco 2040 is a chapter on Natural Hazards, which includes a vision to mitigate wildfire hazards through enhanced fire safety development standards. Goals for implementation under this section include wildfire mitigation plans for development in high-risk areas and encouragement of additional resilient land use planning techniques in high-risk areas.

- Learn more

Further Reading & Resources

- Planning in the Wildland-Urban Interface, American Planning Association

- Community Planning Assistance for Wildfires

Hazard Mitigation Plans

Hazard Mitigation Plans are prepared and adopted by communities with the primary purpose of identifying, assessing and reducing long-term risk to life and property from hazard events. Mitigation planning seeks to break the cycle of damage, recovery and repeated damage and can address a range of natural and human-caused disasters.

Hazard Mitigation Plans typically include four key elements:

- Risk assessment

- Capability assessment

- Mitigation strategy

- Plan maintenance procedures

While most Hazard Mitigation Plans are prepared as stand-alone documents, they can also be developed as an integrated component of a community’s local Comprehensive Plan. Plans can be developed for a single community or as a multi-jurisdictional plan that includes multiple communities across a county or larger multi-county planning region.

The U.S. Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000 amended the federal Stafford Act to require the development of a Hazard Mitigation Plan as a condition for local jurisdictions to receive non-emergency, federal disaster assistance. Like all state and substate jurisdictions, counties must have updated and FEMA-approved Hazard Mitigation Plans every five years to maintain eligibility for pre-disaster and post-disaster grant funding for projects such as mitigation. However, monitoring and updating local plans on a more frequent basis is also an option for counties.

Counties in Action

Kaua’i County, Hawaii

- The County of Kaua’I Multi-Hazard Mitigation and Resilience Plan was updated and approved in 2021. This detailed plan helps in long-term planning for natural hazard risks in the county. This includes wildfires, floods, drought, landslides, erosion, climate change, homeland security threats and health-related hazards. A risk assessment for each hazard includes vulnerabilities and scenario-planning, while specific issues of future consideration are outlined. Kaua’i County was also intentional about including equity assessment and goals in this plan update.

- Learn more

Further Reading & Resources

- Planning for Hazards: Land Use Solutions for Colorado, Colorado Department of Local Affairs

- Hazard Mitigation Planning, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)

Community Wildfire Protection Plans

Title I of the Healthy Forest Restoration Act (HFRA) of 2003 authorizes communities to draft and implement a Community Wildfire Protection Plan (CWPP). CWPPs are developed in a collaborative framework established by the Wildland Fire Leadership Council and agreed to by federal, state, tribal, and local governments and other community stakeholders. The plans provide the framework to both strengthen existing partnerships and build new relationships.

A CWPP typically includes three core elements:

- Identify and prioritize areas for hazardous fuel reduction treatments

- Recommend the types and methods of treatment on both Federal and non-Federal land that will protect one or more at-risk communities

- Recommend measures to reduce structural ignitability throughout the at-risk community.

Through the CWPP process, communities define and map an appropriate boundary for the WUI. The plan is designed to specifically address a community’s unique conditions, values, and priorities related to wildfire risk reduction and resilience. CWPPs may address issues such as wildfire response, hazard mitigation, community preparedness, and/or structure protection.

To maximize synergy between wildfire risk reduction and community land use planning activities, CWPPs may reference comprehensive plan priorities; consider and inform the future land use map as part of wildland-urban planning; and identify opportunities to implement wildfire risk reduction activities – such as defensible space – through the land development code or voluntary, community-led fire-adapted community programs (see Section III & IV of this Toolbox).

Communities with CWPPs are also given priority of federal funding for hazardous fuels reduction projects carried out under the HFRA, including practices such as prescribed fire and mechanical treatments (see Section V of this Toolbox).

Counties in Action

Chaffee County, Colorado

- Titled as a ‘Next Generation’ CWPP, Chaffee County and a variety of partners, stakeholders and residents developed this plan after 16 months of robust engagement and development. The plan includes data, geospatial risk modeling and identifies targeted fuel treatment priorities of “5-10 percent of the landscape to reduce wildfire risk to county by 50-70 percent.” The Next Generation CWPP also identified strategies of community engagement and goals for zoning updates.

- Learn more

Mono County, California

- The Mono County CWPP uses GIS data and science-based analysis, such as the community Wildfire Hazard Rating (WHR) system, to identify geographic areas of concern and outline project recommendations to reduce the threat of wildfire. The Mono County CWPP also includes neighborhood-level threat assessments and tailored recommendations for 36 WUI communities in the county.

- Learn more

Further Reading & Resources

- CWPP Leader’s Guide, International Association of Fire Chiefs

- Land Use Planning to Reduce Wildfire Risk, Headwater Economics

Comprehensive Economic Development Strategies

The Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS) contributes to effective economic development in America’s communities and regions through a locally based, regionally driven economic development planning process. Economic development planning as implemented through the CEDS is a cornerstone of U.S. Economic Development Administration (EDA) programs and engages community leaders, leverages the involvement of the private sector and establishes a strategic blueprint for regional collaboration.

EDA guidelines note that the CEDS should include, at a minimum, an identification of the region’s key vulnerabilities and resilience-building goals, measurable objectives and projects in the action plan. CEDS planning creates an avenue for integrating economic development strategies, sustainability principles and hazard mitigation planning to ensure such activities are undertaken in a complementary fashion. A CEDS can often play an important role in ensuring that disaster mitigation efforts are well-coordinated across both county and municipal lines to shape stronger, more resilient regions. An example of the benefits from this “cross-pollination” planning of CEDS include the strategic siting of new commercial and industrial development in locations outside of hazard areas.

Further Reading & Resources

III. Fire-Resilient Land Use Planning & Development Codes

As early as 1935, community leaders and the federal government were incorporating proactive ideas to reduce wildfire risk in the WUI. The Fire Protection Association, the U.S. Forest Service and other stakeholders drafted a technical guide, entitled Fire Protection and Prevention for Summer Homes in Forested Areas.[3] This guide provided examples of prevention measures including site location and space between buildings; removal of needles and leaves from roofs; and fire-resistant roof materials. While understanding and practices of WUI planning have since expanded, this guide helped lay the foundation for topics and tools local governments are considering and utilizing today.

Counties have a suite of options to regulate land development in the interest of public health, safety and welfare. Often referred to as "the teeth" of the comprehensive plan, land use and development codes implement the goals and priorities identified in the comprehensive plan, or other plans, by regulating how property may be used in a local jurisdiction. Development and implementation of codes and regulations are based on applicable local, state and federal legislation.

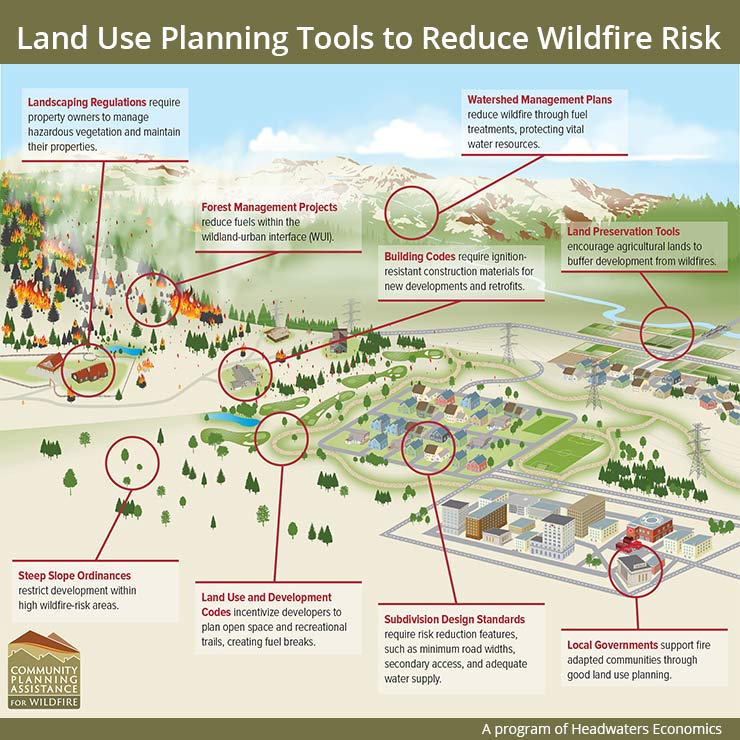

|

Source: Community Planning Assistance for Wildfires |

Codes aimed at wildfire mitigation and existing and future development in the WUI – such as structures, roads and other infrastructure, landscaping, and current and future land uses – can serve a critical role in protecting life and property using proven standards for wildfire risk reduction in the natural and built environment.

Dependent on authority, counties can utilize a variety of tools for land use planning and development code provisions. The following section describes five important options that can be applied to reenforce counties’ wildfire management efforts.[4]

Zoning Ordinances

Zoning ordinances are standards set to govern the use of land and the location, size and height of buildings. While zoning ordinances can vary, they typically share standard elements such as zoning districts, regulations of use, site development standards and administrative requirements.

For wildfire planning, zoning ordinances allow communities an avenue for disincentivizing development in the highest wildfire hazard areas and strategically directing development to safer areas of the community.

Zoning Districts are the fundamental application of land-use regulation. Through base zoning districts or overlay districts, zoning districts are established, delineated and applied through an official zoning map.

- Base zoning districts are traditional districts making up an official zoning map often categorized by type of use (e.g., residential, agricultural, commercial) with development standards that apply throughout a specified district. Base zoning districts can be utilized to match areas of wildfire risk with use of appropriate density. For example, a multifamily residential zone allowing higher density development might not be best suited for areas of wildfire hazard and risk, unless coupled with additional building code provisions. Conversely, a lower-density, large lot residential zoning district might be more appropriate for these areas.

- Overlay zoning districts add additional standards within designated areas to address underlying conditions or priorities, regardless of the base zoning district boundaries. Overlay standards can supplement or even supersede base zoning district standards. An overlay district might be applied to a specific geography, such as mapped high-hazard areas, or certain site characteristics, such as steep slope topography. Standards to reduce wildfire risk within an overlay zone could include requirements for mitigation of risk-prone uses, construction design or vegetation management.

Transfer or Purchase of Development RightsCounties may also be interested in pursuing transfer of development rights (TDR) programs, which allow for additional density in targeted growth areas in exchange for protection of development of open space, agricultural or forested lands in hazardous or environmentally sensitive areas. This tool requires an adopted plan that clearly identifies areas the community desires to preserve or protect from development (“sending areas”) and areas where growth and development are encouraged (“receiving areas”). A closely related approach is a purchase of development rights (PDR) program, in which development rights are acquired from a property owner in an area identified as appropriate for protection and less development intensity. The rights are extinguished rather than transferred. In exchange for selling their development rights, the landowner grants a conservation easement on the property, which permanently protects the land from development. The land may be sold or transferred, but the deed restriction remains in place. These innovative approaches and preservation tools can help reduce density of structures and chances of fire interaction. Well-maintained agricultural and open space lands can also serve as critical fuel breaks to deter spread in a wildland fire event. |

Use Regulations set the allowable and disallowed property uses in a designated area. Along with establishing appropriate zoning districts and the standards within them, the zoning code establishes the appropriate uses of land allowed within each district. This fundamental aspect of zoning is especially important when planning for wildfires. Zoning ordinances establish and communicate what uses of land are allowed in each zoning district. Ordinances typically indicate if uses are allowable by-right or by procedures, such as a conditional use or special use permit.

Use-specific standards can also be applied in the review process, such as establishing mitigation conditions for a specific use to reduce wildfire risk. A local zoning ordinance, for example, might require a fire management plan or establish a minimum distance from hazardous vegetation for certain uses, such as gas stations, lumber yards, shooting ranges, or critical public or community facilities (e.g., schools, health care centers).

Site development standards of a zoning code regulate the physical layout, design, and quality of development. Development standards often address grading and drainage, access and connectivity, parking, landscaping, building design, and signage. The level to which a community regulates site development varies by jurisdiction and location.

- Landscaping Standards seek to address both the amount and type of landscaping as it relates to property. Vegetation management within the structure ignition zone is one of the most common landscaping topics regarding fire and WUI planning. Particular attention is often put toward spacing, thinning, removal and species selection techniques that reduce likelihood of burning vegetation affecting a structure.

- Landscape Maintenance Provisions are commonly intended for aesthetic goals, though they can also serve a wildfire risk reduction role. As with vegetation requirements, landscape buffers can be required to create aesthetic transitions and reduce wildfire threat to adjacent development by serving as a fuel break and defensible space.

- Lot and Building Standards are central to maintaining appropriate density and desired character of zoning districts and include standards such as building setbacks, building height and lot area requirements. Building and lot dimensional standards can play an important role in wildfire risk reduction. The lot size impacts the amount of vegetation within the structure ignition zone. As larger lots are allowed, minimum setbacks from lot lines could be an option to ensure structure ignition zones don’t overlap and can help mitigate home-to-home ignitions.

Subdivision Ordinances

Subdivision ordinances are standards for dividing land into lots or parcels to make the property suitable for development. Regulations typically include requirements for drawing and recording a plot and necessary public improvements such as adequate streets, utilities, drainage, vegetation management and vehicular access. When considering wildfire planning objections, subdivision ordinances can set standards for emergency access, water availability, open space and lot and block design.

Emergency operations and evacuation access is critical to life and safety during wildfire events. Review of new subdivisions should consider adequate ingress and egress of the subdivision and circulation within the subdivision. Coordination between county leaders and fire departments can ensure proper review of design features such as driveway width, length and slope adequate for firefighting vehicles and equipment; multiple driveways for multifamily developments; visible street signage and addresses; and access points into a subdivision.

Water availability to support a new subdivision is always an important consideration, especially in water-scarce regions. Likewise, water is equally important from a fire protection perspective. The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) indicates that subdivision applicants should demonstrate adequate supply for fire suppression, including minimum water levels and flow rates depending on use type (i.e., single-family, multifamily, or nonresidential).

Open Space is another key consideration during the subdivision process. Preserving open space can help protect sensitive areas from development impacts and provide community benefits such as trails and recreation areas. Additionally, well-maintained open space reduces fire hazard by reducing fuels or providing a fuel break. Through subdivision ordinances, dedication of public space or payment of a fee-in-lieu (to be used for acquiring open space) could be required for larger subdivisions of a determined size.

Lot and Block Design is a fundamental element of subdivision. Most subdivision regulations require lots to be designed in a way that complies with applicable zoning district requirements, such as lot width, lot area and overall density. As it relates to wildfire planning, counties could explore additional lot and block design standards to ensure compliance with vegetation management provisions and to avoid particularly hazardous wildfire areas in terms of vegetation type or steep slope topography.

Building Codes

Building Codes are regulations governing the design, construction, alteration and maintenance of structures. Codes set minimum requirements intended to adequately safeguard the health, safety and welfare of building occupants. Building codes and regulations in the United States date back to the late 19th century and their early intent was to reduce fire risk, largely driven by destructive fires in urban areas, such as the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

A home or other structure’s ability to survive in a wildfire is largely based on building materials, design features and landscaping. Homes designed and built to wildfire-resistant standards – often referred to as home hardening – have reduced susceptibility and are more likely to survive a wildfire. Building codes that incorporate WUI mitigation focus on a range of topics, including the selection of fire-resistant materials, construction techniques and landscaping requirements in the structure ignition zone. Several components of the structure can be addressed through these standards, including the roof, gutters and eaves, vents, siding, windows and doors, and decks, fences and other attachments.

Building codes are typically adopted by the state or local jurisdictions through a legislative and public process. Adoption of building codes is not uniform across and within states. In some states, local jurisdictions can adopt even more stringent standards than the state code, while other states have statewide building code standards and do not require additional code adoption at the local level.

Resources many jurisdictions refer to in integrating model code language or standards include the National Fire Protection Association’s (NFPA) Standards for Reducing Structure Ignition Hazards from Wildland Fire or the International Wildland-Urban Interface Code (IWUIC).

Fire Codes

Fire codes are regulations prescribing minimum requirements to prevent fire and explosion hazards, ensure life safety and provide fire access and water supply. Fire codes often work in conjunction with building codes. Intertwining these codes helps to ensure the safety of buildings and their occupants, minimize the risk of fires and explosion hazards and protect first responders. Some jurisdictions may adopt fire codes that are embedded within a building code and others may designate a WUI chapter within the fire code. Fire codes may also remain independent from the building code and WUI code.

The core difference between fire codes and building codes is that fire codes are used for fire prevention on an on-going basis beyond initial construction and seek to ensure building owners maintain building code standards.

Similar to some counties’ subdivision regulations, topics typically addressed through fire codes include access roads, emergency exits, water supplies, emergency planning and preparedness, active and passive fire protection systems (e.g., sprinkler and fire alarm systems), trash and debris management and the storage and use of hazardous materials.

As with the building code adoption process, many states or local jurisdictions adopt a model fire code, such as the International Fire Code or NFPA 1: Fire Code.

WUI Codes

WUI codes are standalone codes, ordinances, or regulations that compile and establish minimum requirements to address wildfire hazard in designated wildland-urban interface areas. Typical topics include vegetation management, construction, water supply and access.

Right-to-Farm OrdinancesRight-to-Farm ordinances, statues or laws gained traction across the U.S. in the 1970’s stemming from a growing concern about the loss of agricultural land. The purpose and intent of right-to-farm ordinances is to protect agricultural operations by limiting the circumstances under which a properly conducted agricultural operation may be considered a nuisance. These statues protect farmers from pursuing nuisance lawsuits against farmers because of odor, noise, slow moving farm equipment or other occasional effects of agricultural production. These ordinances are seen at both the state and local government level across the nation. In many cases, these protections also expand to include forestry practices. These efforts have an effect on land use and wildfire risk, not through use regulations in districts or preservation of property itself, but through the protection of the practice of standard farming or forestry operations. This approach can help keep farmland in use, which can reduce density in certain hazard areas and serve as critical fuel breaks. Forestry practices can, likewise, continue to operate on private lands to thin and maintain healthy forests and reduce fuels and risk. |

Counties in Action

Summit County, Colorado

- Summit County updated their Land Use & Development Code in 2018, including revisions to both zoning and subdivision regulations. These updates include wildfire hazard assessment and mitigation plan for any rezoning; defensible space and landscaping provisions for rezoning and subdivision requests; emergency vehicle access requirements; and prohibition of uncovered firewood storage within 30 feet of a structure during designated wildfire season.

- Learn more

Wallowa County, Oregon

- One of the first counties in Oregon to systematically address wildfire risk in zoning regulations, Wallowa County created the Wildfire Hazard Overlay (WHO) Zone. Congruent to the county Comprehensive Plan and Community Wildfire Protection Plan, the WHO zone includes designated WUI and additional ‘Communities at Risk’ areas. New structures built in this overlay zone must have proper emergency access; include an encompassing fuel-free break area; have non-flammable material roofs; and be within a fire protection coverage area with the water necessary for fire suppression.

- Learn more

Routt County, Colorado

- First launched in 1997 and reapproved by voters in 2005 to run through 2025, the Routt County Purchase of Development Rights (PDR) Program is an open space and agricultural preservation tool to help the county protect rural character, wildfire habitat and natural resources and deter development in hazard and sensitive areas. Through this program, Routt County has helped fund the purchase of conservation easements on 50,105 acres.

- Learn more

Further Reading & Resources

- Planning in the Wildland-Urban Interface, American Planning Association

- Wildfire Risk to Communities

- Community Wildfire Planning Center

- Community Planning Assistance for Wildfire (CPAW)

IV. Fuel Reduction: Fire Adapted Homes & Communities

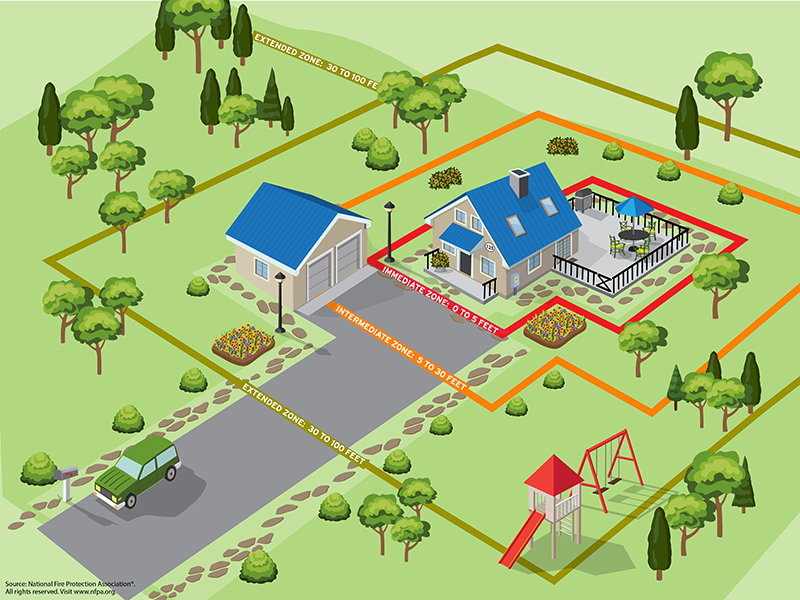

The majority of homes lost to wildfire are first ignited by embers and small flames. By reducing the susceptibility of the area immediately around a home or other structure – the structure ignition zone – the chances of a structure surviving an ember storm or small spot fire are greatly decreased. Efforts to reduce risk and susceptibility are referred to as creating defensible space. As already noted, efforts to decrease susceptibility and increase likelihood of survival of the home itself is often referred to as home hardening.

While local regulations can play a role in building fire-adapted homes and communities, the work of defensible space and home hardening is often also done on a voluntary and community and resident-driven basis. Programs such as the national Firewise USA program provide a framework and support to help neighbors and communities organize, find direction and take action to increase ignition resistance and reduce wildfire risk. Firewise USA is administered by NFPA and is co-sponsored by the U.S Forest Service and the National Association of State Foresters.

Fire Mitigation Approaches by Structure Ignition Zones

Source: Wildfire Risk to Communities, wilfirerisk.org ; NFPA |

Counties and county leaders can increase public awareness and education regarding home hardening and defensible space strategies for residents and garner support for local action.

Counties in Action

Lane County, Oregon

- The Lane County Firewise Grant Incentive Program is administered by the county’s Land Management Division’s Long Range Planning & Building programs and offers homeowners in rural Lane County financial assistance to make their homes better able to survive wildfires. Available funding can support improvement projects, such as removing ladder fuels, clearing brush, using noncombustible landscaping materials, installing fire-resistant windows and installing noncombustible exterior home siding.

- Learn more

Chelan County, Washington

- Created for long-term residents, new residents and visitors alike, the Chelan County Good Neighbors Handbook includes a section on "Living with Wildfire." This guide outlines educational information on county fire history, home ignition zone basics, fire-resistant plants and links to local and state fire resources.

- Learn more

Santa Clara County, California

- The Santa Clara County Firesafe Council (SCCFSC) is an example of the impact that a grassroots community and neighborhood-level initiative can have in wildfire preparedness and mitigation through education and project assistance. Like other Firesafe Councils across California, SCCFSC offers a community chipping program available to process brush, tree limbs and other fuels that have been removed by residents for defensible space maintenance and then turned into wood chips for landscaping and other appropriate uses.

- Learn more

Further Reading & Resources

- Firewise USA, National Fire Protection Association

- Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network

- Wildfire Risk to Communities

- California Fire Safe Council

V. Fuel Reduction: Resilient Landscapes

A key strategy for reducing wildfire risk in a landscape is to reduce the amount of available fuel a fire can consume. Managing and reducing fuel reduces the extent, intensity and severity of wildfire if and when it encounters a treatment area. The three primary means of managing wildland fuels are:

- Prescribed fire

- Managing fire for resource objectives and ecological purposes

- Non-fire treatments involving mechanical, biological or chemical methods.

While much of this work may occur in national forests or other federal lands, counties play an important role in partnership, planning and implementation of this fuel management work. Further, forested landscapes stretch beyond the borders of federal lands and may exist as private, state or local government-owned public lands. County land management practices and planning approaches therefore should be included in comprehensive strategies and the suite of tools and resources available.

Prescribed Fire, also referred to as planned fire or controlled burn, is one of the more effective and cost-efficient means of managing vegetation for multiple purposes, including hazard reduction and ecosystem restoration. Prescribed fire reintroduces the beneficial effects of fire into an ecosystem by safely reducing brush, shrubs and trees; encouraging new growth of native vegetation, therefore reducing the hazard of catastrophic wildfire caused by excessive fuel buildup. Prescribed fire does carry inherent risk as fires can escape the prescribed perimeter or produce hazardous smoke, so proper and professional management is imperative.

Managing Wildfire for Resource Objectives refers to a strategic choice to use unplanned ignitions to achieve resource management objectives. The goal of managing fires for resource benefits is to allow fire to resume its natural role in the ecosystem. Historically, natural fires create a mosaic of different vegetative types. In turn, these vegetative patterns create a diversity of habitats. Naturally ignited fires are managed by professionals to accomplish specific resource management objectives within predefined geographic areas. Not simply a “let it burn” approach, fire planners must assess risk, predict fire behavior and growth, plan for contingencies and determine the maximum limits of the fire area, called maximum manageable areas (MMA).

Non-Fire Fuel Treatment, such as mechanical, biological or chemical, is an approach with many advantages such as greater outcome control and reduced risk of unintended consequences. Mechanical treatments include the thinning of dense stands of trees, piling brush, pruning lower branches of trees or creating fuel breaks. Tools that are used to carry out the mechanical treatment of hazardous fuels range from hand tools such as chainsaws and rakes, to large machines like bulldozers and wood chippers. Mechanical treatment can be used on its own or together with prescribed burning to change how wildfire behaves, so that when a fire does burn through a treated area, it is less destructive, less costly and easier to control. Often, mechanical fuel treatments are followed by prescribed fire to create effective hazard reduction. Mechanical treatment can also open opportunities for county economic and resident well-being through woody biomass utilization for wood products or for new renewable energy sources.

Counties in Action

Deschutes County, Oregon

- As a key partner in the Deschutes Collaborative Forest Project, the county works to help reach healthier more resilient forests and safer communities. Through both prescribed fire and mechanical thinning and logging, DCFP’s work has resulted in restoration of tens of thousands of acres of forest. Additionally, 400 jobs have been created through projects in the DCFP landscape, ranging from harvesting trees, forest biomass and other value-added wood products. This effort is supported by the U.S. Forest Service Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program.

- Learn more

Chaffee County, Colorado

- Following a robust community planning initiative Envision Chaffee County, Chaffee County voters approved a quarter-cent sales tax increase in 2018 to launch Chaffee Common Ground. Chaffee Common Ground funds efforts in forest restoration and rural, working lands preservation across the county in priority areas. One-third of these priority forest treatment areas are privately-owned.

- Learn more

Further Reading and Resources

- Western Region, National Cohesive Strategy

- Prescribed Fire, U.S. Forest Service

- Confronting the Wildfire Crisis, U.S. Forest Service

VI. Resources & Reading

- Planning the Wildland-Urban Interface – American Planning Association PAS Report 594

- Wildfire Risk to Communities – USDA Forest Service, Headwaters Economics, Pyrologix

- Community Planning Assistance for Wildfire(CPAW)

- Community Wildfire Planning Center

- Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network

- Firewise USA – National Fire Protection Association

- Ready, Set, Go! Program – International Association of Fire Chiefs

- Wildland Fire Assessment Program – National Volunteer Fire Council

- AIM: Action, Implementation & Mitigation – Coalitions and Collaboratives, Inc

- Community Mitigation Assistance Team – USDA Forest Service

- Land Use Planning to Reduce Wildfire Risk: Lessons from Five Western Cities – Headwaters Economics

- Prepare for Wildfire – Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS)

- County Wildfire Playbook – National Association of Counties (NACo)

- WiRe Wildfire Research Center

- Conservation Gateway – The Nature Conservancy

- National Interagency Fire Center

- After the Fire: Resources for Recovery – USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service

- Building Community Resilience with Nature-Based Solutions – FEMA

[1] Confronting the Wildfire Crisis: A Strategy for Protecting Communities and Improving Resilience in America’s Forests. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. January 2022.

[2] The National Strategy: The Final Phase of the National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy. U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Interior. April 2014.

[3] Planning in the Wildland-Urban Interface. American Planning Association PAS Report. April 2019.

[4] Planning in the Wildland-Urban Interface. American Planning Association PAS Report. April 2019.