Counting the Costs Of Post-Disaster Reimbursement: County Fiscal Impacts of Federal Disaster Response

Upcoming Events

Related News

Pending disaster claims often represent significant sums of money. Seven percent of respondents in a recent NACo survey indicated reimbursement claims totaled between

$50 and $100 million, and 46 percent of respondents report total claims between $1 million and $25 million.

County claims processing varies by project and disaster. One in five counties (20 percent) indicated the longest open claim has been in processing between four and six years; the largest share (28 percent) report processing times exceeding six years. For counties with all outstanding claims paid, the majority (71 percent) report typical turnaround times between one and three years.

Because counties are the primary responders to disaster incidents supplying public safety, emergency management and rescue resources, the cost of response efforts are paid upfront using county funds. With expected reimbursement timelines of at least one year, counties must take steps to maintain net positive cash-flow post- disasters to continue service delivery. To accomplish this, some counties have resorted to measures including short-term loan financing or bond issuance.

Natural disasters have wide-ranging impacts on county government finances and operations

Pending disaster claims often represent significant sums of money. Seven percent of respondents in a recent NACo survey indicated reimbursement claims totaled between

$50 and $100 million, and 46 percent of respondents report total claims between $1 million and $25 million.

County claims processing varies by project and disaster. One in five counties (20 percent) indicated the longest open claim has been in processing between four and six years; the largest share (28 percent) report processing times exceeding six years. For counties with all outstanding claims paid, the majority (71 percent) report typical turnaround times between one and three years.

Because counties are the primary responders to disaster incidents supplying public safety, emergency management and rescue resources, the cost of response efforts are paid upfront using county funds. With expected reimbursement timelines of at least one year, counties must take steps to maintain net positive cash-flow post- disasters to continue service delivery. To accomplish this, some counties have resorted to measures including short-term loan financing or bond issuance.

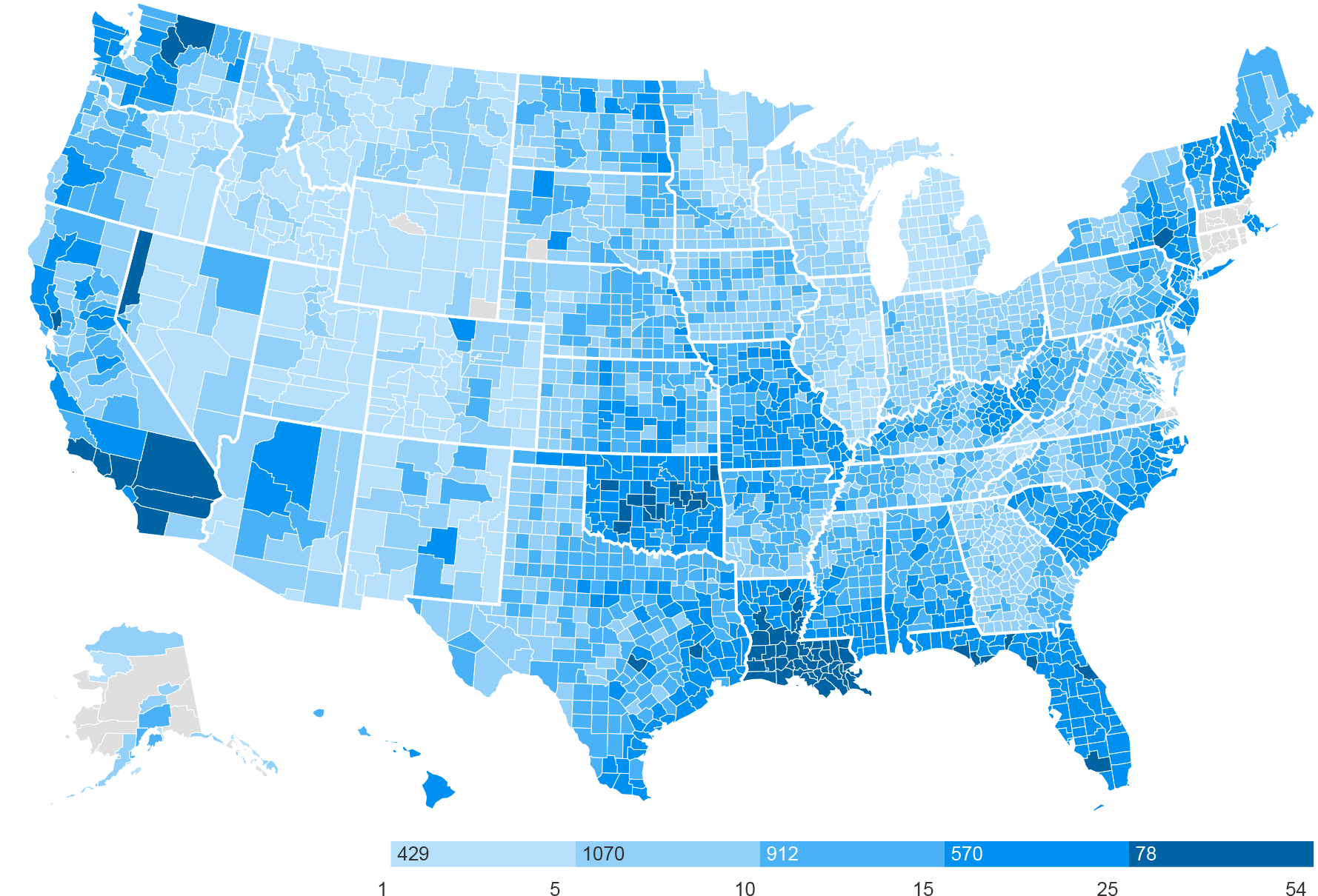

Ninety-three percent of respondents have experienced a presidentially declared disaster in the past ten years.

Of those counties who have experienced a disaster, nearly three quarters have outstanding reimbursement claims

Source: NACo survey of county membership, October 2023.

Disaster Claims

$237 – $665 M

Total Outstanding Claims

1-3 Years

Typical Claim Turnaround Time from Incident to Payment and Closeout

Top Three County Cash-flow Measures Taken While Waiting For Reimbursement Funding

18%

Austerity Measures

11%

Loan Financing

10%

Bond Issuance

The most common type of disaster in the past twenty years has been fires (41 percent), with severe storms and hurricanes falling in behind at 28 percent and 12 percent, respectively.

Since 2003, there have been more than 2,500 non- COVID-19 related disasters that have risen to the level of a presidentially declared incident. Under the Stafford Act, enacted in 1988, a president can declare a national disaster incident at the request of the Governor of the impacted state when it is determined that federal assistance from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is needed for local governments to respond and recover.

The most common type of disaster in the past twenty years has been fires (41 percent), with severe storms and hurricanes falling in behind at 28 percent and 12 percent, respectively. Other types of disasters range from flooding and snowstorms to drought, earthquakes and freezing temperatures. In total, there are over 22 distinct types of non-COVID-19 disasters that have occurred over the past 20 years.

There are two types of declarations, emergency and major disaster. Under both, counties are eligible to receive a portion of Public Assistance (PA) funding from FEMA. Emergency declarations limit PA funding to debris removal and emergency protective measures – category A and B projects). Major disaster declarations expand eligible projects to include roads and bridges, water facilities, buildings and equipment, utilities and parks or recreation facilities – category C – G projects, otherwise known as permanent work.

General Timeline For FEMA PA Claim Processing

Incident, Declaration & Assessment

Project Worksheet Development

Response and Cleanup Work

Project Reimbursement Application

Review, Processing & Obligation

Post-Award Monitoring

Final Reconciliation, Payment & Closeout

The FEMA PA disaster reimbursement process is complex and involves multiple intergovernmental agencies. At the local level, counties receive funds as a sub-recipient of the state. Each disaster declaration and reimbursement process can have specific requirements and variations depending on the type, level of damage and state provisions.

In general, from the moment a disaster declaration occurs, a clock starts for counties to submit reimbursement applications. Counties must first work with state agencies to request assistance and conduct a preliminary assessment of the damage and necessary projects. While counties conduct cleanup and response efforts, information is collected on the scope and costs associated with each project.

Final cost and project information is submitted to state agencies for review, and information is subsequently passed on to FEMA for additional review. Review is typically the longest part of the reimbursement process where county information is subject to audits, revisions or verification. Once the projects are approved, funding is obligated to the county and ultimately reimbursed after the project work has concluded and all reconciliation is complete.

There are several hurdles counties must overcome throughout the reimbursement process. At the local level, there are disparities in county capacity and resources needed to collect and submit information, and federal support is complex and often slow. Furthermore, disasters are expensive and difficult to budget for. Public assistance funding requires a local match, typically 25 percent, though some disasters receive exclusions. Finally, there are several layers of review, regulation and reporting that can be difficult to navigate. The complexity of the process requires frequent communication between local, state and FEMA staff, but often there are workforce challenges, such as turnover, that disrupt the process.

County survey respondents reported fronting between $237 - $665 million in currently outstanding claims.

Disasters are local, meaning counties are often left to pay upfront costs associated with disaster mitigation, response, recovery and rebuilding. County survey respondents reported fronting between $237 - $665 million in currently outstanding claims. The most common type of project counties seek reimbursement for is debris removal. Many of these projects can be broken into smaller projects, which allow counties to receive expedited reimbursement under the FEMA PA small projects funding cap of $1 million.

Because larger projects require more funding and exceed the cap, it often takes months or years to process reimbursement. Many of these larger projects are components of critical infrastructure like water pumps, roads, bridges and county facilities. Disasters do not happen in a predictable manner, meaning it is essential for counties to pay for these projects upfront, so they are operational for any future incidents.

For counties in disaster prone regions, the increasing costs and frequency of disasters has significant ramifications on the long-term fiscal outlook. Benchmarking past disaster costs is a common strategy for county fiscal officers when budgeting for disaster incidents. Inflation and the increasing costs of repair and disaster-related services are also straining county budgets. Extended timelines for project reimbursements, coupled with the rising costs from increased frequency of disasters and inflationary forces is leading to tough decisions for counties needing to balance budgets and continue funding government operations.

For the counties with outstanding claims, 73 percent report their longest outstanding claim has been pending reimbursement for longer than two years.

For the counties with outstanding claims, 73 percent report their longest outstanding claim has been pending reimbursement for longer than two years. The largest share (28 percent) report the longest claim pending reimbursement greater than six years. For counties with all outstanding claims paid, the majority (71 percent) report typical turnaround times between one and three years.

Just as the total of outstanding project reimbursements increase difficulty for county budget managers, extended timelines also impact county cash flow. Counties have limited financial resources to operate services, pay county staff and conduct disaster response and rebuilding efforts. When reimbursements are delayed, it can lead to a cash crunch, affecting the county’s ability to meet financial obligations and creating volatility within county budgets. This may result in cutting back on essential services, which can be particularly detrimental to vulnerable residents grappling with disaster impacts.

Extended reimbursement timelines can also strain the relationship between counties and other levels of government. When reimbursements are consistently delayed or take an excessive amount of time to process, it can create tension between counties and the agencies responsible for reimbursement. This strained relationship could result in decreased collaboration, communication, and support from intergovernmental partners, further exacerbating the negative fiscal impact on the county for future disaster incidents.

Delays in reimbursement funding may hinder a county’s ability to plan effectively for future disasters.

The most common measure counties took to maintain cash-flow positive while waiting for disaster reimbursements was budget austerity – cutting from other areas to balance the budget. When officials are forced to take austerity measures, county employment and critical infrastructure investments are usually the first to be cut or deferred, as demonstrated during COVID-19 when counties faced significant operating shortfalls.¹ As such, austerity measures create a rippling effect that can negatively impact service delivery and the long-term infrastructure health of the community.

Seventeen percent of counties also reported taking other measures, like shifting maintenance timelines or securing an advance on FEMA funding. For the counties that did not need to take fiscal measures, the most common method to keep cash-flow positive was relying on rainy day or reserve funding (77 percent of respondents).

Despite county strategies to remain cash-flow positive, there are long-term impacts that are out of the hands of fiscal officers. Delays in reimbursement funding may hinder a county’s ability to plan effectively for future disasters. This uncertainty can compromise a county’s ability to stockpile emergency supplies, invest in disaster preparedness measures, or establish robust contingency plans.

When counties are eventually reimbursed, there is often a net negative return. Between October 2021 and October 2023, the cost of goods and services rose more than 11 percent; over the past six years, costs have increased by nearly a quarter (24.7 percent).² Counties are reimbursed at the cost reported, without interest, meaning counties that needed to issue bonds or take loans are having to pay interest on that debt, which is not reimbursed, leading to a negative real return on money fronted on behalf of FEMA.

County cash-flow was the most impacted aspect of county fiscal health; 24 percent of respondents report a heavy impact, while 70 percent reported moderate or light impacts.

Fronting disaster reimbursement funding can have significant fiscal implications for counties. Both the volume of outstanding reimbursements and the time it takes to be reimbursed can contribute to severe cash flow problems. This can result in budget shortfalls, necessitating the reallocation of funds from other essential county services like education, healthcare, and public safety.

Furthermore, fronting reimbursement funding can negatively affect a county’s ability to maintain a net positive cash flow. This could have implications for paying vendors, internal budgeting for operations and services and necessitate the use of other fiscal measures that lead to a vicious and precarious cycle to preserve cash flow management. County cash-flow was the most impacted aspect of county fiscal health; 24 percent of respondents report a heavy impact, while 70 percent reported moderate or light impacts.

Similarly, depleting reserve funding can negatively impact a county’s debt to asset ratio, which is an important metric when determining creditworthiness or bond ratings. The implications of downgraded bond ratings and decreased credit typically result in higher interest rates on future loans and bonds. Consequently, fronting disaster reimbursement funding can have long-term financial ramifications for counties, increasing borrowing costs and limiting the ability to invest in critical infrastructure, capital improvements or other essential projects.

Public works and county staffing were the second and third most impacted areas reported by county leaders. Due to the work of county budget managers taking steps to maintain positive cash flow, county credit ratings have had the smallest direct impact. There are a number of strategies counties can employ to maintain cash flow aside from loans, bonds and dipping into reserve funding.

The disaster recovery process represents one of the prime examples of the need for a strong intergovernmental partnership.

The disaster recovery process represents one of the prime examples of the need for a strong intergovernmental partnership. Federal, state and local governments are all intertwined in the efforts to get communities back to normal as quickly as possible. This process is often understood as federally supported, state managed, locally executed. However, there are some needed reforms to this process to ensure communities are able to respond, recover and rebuild.

Ensuring equitable and efficient access to FEMA Public Assistance by reducing burdensome applications and increasing transparency

The FEMA Public Assistance (PA) Program provides vital aid to counties to support response and recovery efforts from major disasters. However, the application process and determination of eligible funds can oftentimes be complex and difficult to navigate. FEMA should implement changes to the PA program that reduce the administrative burden on counties and work to increase transparency during the process, such as creating a dashboard for counties to monitor their progress throughout the lifecycle of a PA reimbursement claim.

Increasing funding for Emergency Management Performance Grants (EMPG) program and mitigation grants to support local hazard mitigation and preparedness

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) EMPG program assists state and local governments in their efforts to protect their communities from natural and man-made disasters and is the most demonstrably successful DHS grant program. EMPG should remain an all-hazards program that is funded separately from all other grants that specifically address terrorism, COVID-19, or other specific issues at or above current funding levels. NACo appreciates Congress’ action through the Disaster Recovery Reform Act (DRRA) to reauthorize EMPG through 2022. States should be required to pass through a minimum of 70 percent of EMPG funds to local governments.

Reauthorizing and reforming the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) to improve affordability, mitigation assistance, flood risk mapping and program administration

The NFIP was enacted in 1968 to offer residents and businesses federal flood insurance. Although the program is voluntary, communities are heavily incentivized to participate in NFIP, because if a community does not participate, its property owners cannot purchase flood insurance policies. With the current authorization of the program set to expire on March 8, 2024, Congress should act to reauthorize the program with a focus on affordable rates, transparent mapping, and consumer protection. Additionally, counties urge FEMA and Congress to examine the full impacts of the recently implemented Risk Rating 2.0 (RR 2.0), which has dramatically increased flood insurance rates across the country. FEMA should provide tailored training to local officials about RR 2.0, develop a public facing portal to display risk factors and make modifications to the methodology that more accurately reflect the property and community level mitigation measures. Absent of action from FEMA, congress should consider and pass legislation that requires FEMA to increase transparency on RR 2.0 and works to relieve policy holders from large scale increases to annual premiums.

County Spotlight on Disaster Fiscal Impacts

Lafourche Parish, La.

Number of Presidential Disaster Declarations Since 2017: 20

Total Outstanding Claims: $160 million

Lafourche Parish is a rural county on the southern coast of Louisiana. Located adjacent to the Gulf of Mexico, 15 of the 20 disasters since 2017 have been related to a tropical storm. The most recent disaster was Hurricane Ida, which left an estimated $200 million in damages within the county.

In preparation for the disaster, the parish expended $5 million in creating sandbags and paying overtime for county staff. Once Hurricane Ida hit, there was significant debris pickup ($30 million), county response staffing ($1.2 million) and damage to critical infrastructure required.

In previous years, the parish experienced a reimbursement timeframe of 2 – 3 years. However, under the new model of reimbursements, the average time has increased to 3 – 4 years. To ensure the parish can repair damaged infrastructure and support positive cash flow, parish officials issued $120 million in bonds, $10 million more than the annual operating budget. The increase in debt caused a slight downgrade in the parish’s bond rating, meaning future issuances will be at higher interest rates. In addition to the bond issuance, parish officials have had to postpone projects including the rehabilitation of seven bridges.

Grappling with disasters is not new for Lafourche Parrish, as local leaders are still awaiting reimbursement for some project costs associated with Hurricane Gustav in 2008. While the parish awaits repayment, the costs of material and labor continue to increase, and interest accumulated is not currently eligible for reimbursement.

Citrus County, Fla.

Number of Presidential Disaster Declarations Since 2017: 15

Total Outstanding Claims: $150,000

Located on the southern end of the “Big Bend” in Florida, Cirtus County’s primary disaster incident is from hurricanes. Though the county has experienced several hurricanes over the past five years, most of the damage has been debris-related, the majority of which has been able to be reimbursed within two to six months. The only current outstanding claim for $150,000 is to cover additional debris costs and protective measures, not including claims that were recently submitted to FEMA for Hurricane Idalia which impacted Citrus County in August 2023. Because this is a relatively small amount, the county has been able to maintain cash flow by using reserve funds while waiting for reimbursement.

Though disasters haven’t yielded significant fiscal impacts on Citrus County, the amount of staff time required to prepare and manage the reimbursement process has not been trivial. In the wake of the disaster, staff can spend as much as 90 percent of working hours gathering the information necessary to submit a reimbursement claim. The reallocation of time could mean that other projects or service delivery are put on hold until reimbursement activities are concluded.

Sonoma County, Calif.

Number of Presidential Disaster Declarations Since 2017: 18

Total Outstanding Claims: $120 million

Located in northern California’s wine country, Sonoma County is exposed to severe flooding and fire incidents. In the past five years, there were five disasters related to flooding, and three related to wildfires.

While the county has received funding for all reimbursements prior to 2017, there are still 10 open events with more than 100 project claims totaling roughly $120 million in outstanding funds. To maintain county functions while waiting for reimbursements, the county has established a disaster relief fund using seed money from legal settlements for previous disasters. Additionally, the county has established an internal control process for shifting funds from one line item to another to effectively loan the disaster fund additional dollars as needed.

While these solutions work in the short-term, some disaster claims have taken upwards of five years to process which can strain adjacent budgets and lead to postponements on critical projects. For example, county officials are still working with FEMA and Cal- OES to get several Category C permanent projects to repair/replace critical infrastructure related to the 2019 February floods event. Moreover, Sonoma County has had to hire additional full-time staff to process and manage the disaster reimbursements. Though reimbursement claims have provisions for administrative costs, the five percent share eligible to Sonoma County does not cover all the expense for the team. Between increased staffing costs and setting aside additional reserve funding, the county has managed to avoid significant direct fiscal impacts, but the reimbursement process has had rippling effects, nonetheless.

Marion County, Ore.

Number of Presidential Disaster Declarations Since 2017: 9

Total Outstanding Claims: At least $6 million

As a mid-sized county in the Pacific Northwest, Marion County is a frequent spot for wildfire disasters, which have accounted for four of their past seven disasters. For many of the rural municipalities in the county, similar to rural communities across the country, there are limited resources and administrative support to navigate the FEMA PA process for reimbursement after a natural disaster.

To support the residents in these communities, Marion County established the Community Services District in 2015 which helps to provide various levels of support to the incorporated cities, particularly the cities of Gates and Detroit.

In 2020, the Beachie Creek wildfire burned nearly the entire city of Detroit, causing an estimated $6 million in damages. The water treatment facility, a critical piece of community infrastructure was destroyed in this disaster. In immediate response to the incident, Marion County provided funding to the impacted municipalities, including Detroit, to sustain services and sought out grant funding to support longer-term efforts. However, more than three years after the disaster, there have been minimal FEMA PA obligations approved. One crucial challenge in applying for reimbursement has been obtaining matching funding, which oftentimes will far exceed available funding in rural communities. For residents living in these communities, the importance of an easy-to-navigate reimbursement assistance application and timely delivery of funding to rebuild and mitigate future disasters cannot be overstated.

Santa Cruz County, Calif.

Number of Presidential Disaster Declarations Since 2017: 11

Total Outstanding Claims: $64.9 million

Southwest of the bay area, Santa Cruz County grapples with severe storms, flooding and wildfires that lead to significant amounts of debris and road damage, particularly in the rural areas of the county. In total the county has more than 250 outstanding claims pending reimbursement, totaling nearly $65 million. Only 24 percent of claims from recent disasters have been paid, including only 30 percent of the damages from the CZU lightning complex fire.

Because waiting for reimbursement claims has become commonplace, the county has needed to obtain an annual loan. In the past the loan was done to prioritize liquidity but has since transitioned to becoming a necessity to make payroll. In 2023, the loan amount exceeded $60 million. The continued need to rely on loan funds has forced complex decisions from county budget officers. Due to the interest payments associated with loan financing, the county ends up paying more money than what FEMA owes, creating a vicious cycle.

The nature of disaster damage further complicates the situation, as many of the repairs are critical to maintain a level of safety in the community. Often storms will leave devastating damage to roadways in rural areas, leaving residents with limited options and access, and complicating the county’s ability to provide emergency services to the affected areas.

As county leaders confront these challenges, the long- term outlook is precarious. In the most likely scenario, the county will be forced to make complex decisions including shrinking operations to maintain solvency.

Dare County, N.C.

Number of Presidential Disaster Declarations Since 2017: 9

Total Outstanding Claims: All paid except for COVID-19

With 110 miles of coastline, Dare County is no stranger to natural disasters – most frequently in the form of hurricanes. The most recent disaster in the county was Hurricane Dorian in 2019, which left uneven impacts across the county. Since the implementation of the FEMA grants portal and the county’s first use of the new system to process claims for Hurricane Matthew, the reimbursement process has become more routine with quicker turnaround times than expected, with some payments arriving as soon as sixty days after the final documentation has been submitted.

Because of these positive improvements, the county has been able to avoid significant fiscal implications resulting from natural disasters. Funding to cover immediate costs are generally paid upfront from the disaster recovery reserve, which generally maintains a balance of one percent of the general fund annual budget.

One significant fiscal challenge facing county leaders is the impact of geolocation on the county’s credit rating. As a jurisdiction located in an area with a high risk of flooding and hurricanes, the credit rating for Dare County denied an upgrade from AA+ to the AAA level, despite all metrics meeting the thresholds required for an upgraded status. Though the county maintains a high credit rating, the denial of an upgrade due to the geographic risks, and despite the county’s documented mitigation projects, speaks to the long-term concerns for natural disasters impact on the community.

Sources

FEMA Disasters Data: U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency; Disaster Declarations Database for States and Counties, October 30, 2023. Available at www.fema.gov.

Fiscal Implications Survey: More than 130 responses were collected from counties budget officers, elected officials, administrators/ managers, emergency management staff or other senior leadership. County responses represent communities of all population sizes, political affiliations and geographic regions.

Fiscal Implications Case Studies: Case study information is derived from direct interviews with senior county leadership.

¹NACo Comprehensive Analysis of COVID-19’s Impact On County Finances and Implications for the U.S. Economy, 2020; available at: www. naco.org.

²NACo Analysis of U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index.

Notes

All analyses are based on 3,069 counties with active county governments. Thus, Connecticut, Rhode Island and portions of Alaska and Massachusetts are excluded since they do not have active county governments. Independent cities in Virginia are also excluded from the analysis.

New York City is a consolidation of the five boroughs of the city of New York:

- Manhattan (New York County)

- The Bronx (Bronx County)

- Brooklyn (Kings County)

- Queens (Queens County)

- Staten Island (Richmond County)

All listed outstanding claims in the county case studies are as of the interview date. Some counties have since had more claims opened from recent disasters, while others have been able to move forward in the reimbursement process.

Authors

Brett Mattson

Resource

Future-Proofing County Property Now and Beyond: A Summit on Disaster Preparedness and Insurance