Student-led Hope Squads give students a peer to talk to

Key Takeaways

Millie Ferretti recently completed the seventh grade. She plays volleyball, loves to crochet and provides peer suppport for her classmates through Walworth County, Wisc.’s school-based suicide prevention program, Hope Squad.

“Middle school is kind of hard for all of us,” Ferretti said. “So, I just want to be one of those friends that people can ask for help.”

The peer-to-peer approach of Hope Squad was created after it was discovered that only 25% of students confide in an adult when a peer has expressed having suicidal thoughts. Four out of five individuals considering suicide give some sign of their intentions, either verbally or behaviorally, but students often don’t feel comfortable sharing those feelings with an adult, and peers who they confide in often don’t report their peer’s feelings in fear of betraying them or because they’re unaware of how to help, studies show.

“I feel like it’s easier to talk to your friends in some situations, because you’re around your friends a lot and you know and trust them,” Ferretti said. “With teachers, it’s more like they’re there to teach you and it can be hard to talk to them sometimes because they’re a lot older than you.”

Students who are struggling with suicidal ideation and want to seek help, but might feel scared or uncomfortable seeking out support from an adult, go to students in their grade’s Hope Squad to express their feelings. Hope Squad members then connect them to resources and support from a counselor or Hope Squad advisor.

“They know that they can talk to us more [than other students], because we won’t judge them or make fun of them,” Ferretti said.

Hope Squad members are nominated by their peers, which is an intentional continuation of the peer-led model the program operates on, according to Holli Wilke, Walworth County Department of Health and Human Services’ public health supervisor.

“They’re the ones that are identifying people that they trust,” Wilke said. “And generally speaking, students will land on the same top three to five [students], so they tend to be natural helpers and students that are already serving as peer support for others.”

Just because students are nominated doesn’t mean that they have to go through mental health training and serve as a Hope Squad member if they or their parents are uncomfortable with the process, Wilke said. However, most are excited to be in a position to provide support to their peers, she added.

The students who proceed with the process go through an online curriculum of evidence-based suicide prevention training, which functions through the “QPR” model of “question, persuade and refer.” Students learn how to identify signs and symptoms of suicidal ideation or distress, how to intervene and how to connect them to help, according to Nikki Christensen, a Hope Squad advisor and social worker in Walworth County Schools.

In 2023, more than 20% of teens reported having “seriously considered” suicide, according to the American Psychological Association, and suicide is the second leading cause of death for children ages 10 to 14. More teens and young adults die from suicide than from cancer, heart disease, AIDS, birth defects, stroke, pneumonia, influenza and chronic lung disease, combined.

“The biggest thing is the students that they have brought to us that we weren’t aware of who were struggling and needed help,” Christensen said. “Some of the kids who fly under the radar — they’re always happy smiley, they’re involved in lots of activities and maybe it’s not so easy to see that they’re having a hard time with something.

“But then our Hope Squad kiddos were able to bring some of those kids to us and say, ‘They actually are having a hard time, this is going on at home and they do need someone to talk to. I told them that you would come see them.’ Connecting us to students in that way has been really impactful.”

Hope Squad advisors are often school psychologists or social workers, like Christensen, but any school employee who expresses an interest and passion in mental health support can become one, Wilke said.

“We have some gym teachers, music teachers, a front desk worker,” Wilke said. “You name it, it runs the gamut.”

To be a Hope Squad advisor, teachers and counselors go through six hours of training on confidentiality, mandated reporting and the program’s curriculum, which differs depending on age group. For elementary school students, the lessons revolve more around anti-bullying, how to be a good friend and how to listen to your classmate’s feelings, while the middle and high school programming is centered on suicide prevention, according to Christensen.

Ferretti, who went through Hope Squad training as a sixth grader and hopes to continue to serve as a mentor throughout high school, said she learned a lot through the training, including that there are more mental illnesses than depression, she said.

The Walworth County Board of Supervisors devoted American Rescue Plan Act funding to offer Hope Squad in all of the county’s 42 schools — private and public elementary, middle and high schools. The county’s Department of Health and Human Services worked closely with the school district during the pandemic, which led to the implementation of the mental health support programming, according to Carlo Nevicosi, the county’s director of Health and Human Services.

“We heard from them what they were seeing on the ground with students,” Nevicosi said. “And we just went into the lab here and looked at what kind of opportunities, what kind of investment we could make that would have an impact not just at one school, but countywide.”

There are currently 15 Hope Squads in Walworth County, with roughly 50 advisors and 350 students. Hope Squad has been implemented in thousands of schools across the country, but it’s usually funded by an individual school or the district and not the county, according to Nevicosi. Although the county’s ARPA funding runs out this month, the cost of Hope Squad for the county was frontloaded, revolving around implementation and training, so the schools can continue to utilize the program at little to no cost, Nevicosi said.

“We helped keep the [Hope Squads] glued together and build their own network of support,” Nevicosi said. “So, it’s an approach, a cultural movement, that feeds itself, because the schools were faced with the decision about ‘Why not? Why wouldn’t we do this? If there really isn’t any cost to us, and our neighbors are doing it and having a good experience with it?’”

At one school in the county, Hope Squad members serve as mentors to new students. At another, they sit with people who they don’t know well or someone who’s sitting alone at lunch. Because Hope Squad can look different school-by-school, advisors throughout the county meet monthly to exchange best practices and share resources, according to Wilke.

“We’re a rural community, and we tend to get really siloed in our municipalities, especially in school districts,” Wilke said. “So really kind of taking that community-wide approach and raising awareness, I think, is essential.”

One of the schools helped organize a 5k for the nonprofit Bigger Than the Trail, which pays for therapy for people who don’t have insurance or can’t afford it. The schools also held an “All School Hope Week,” to promote wellness and encourage having conversations about mental health. Hope Squad has helped tremendously to normalize talking about mental health in Walworth County Schools, Christensen said.

“They’re not ashamed,” Christensen said. “They feel passionate about mental health and are open about it and reducing the stigma. I’ll have first graders who participate in Hope Week and get to see the kids in their Hope Squad stuff, and they’re like, ‘I want to be on Hope Squad, Ms. C!’ It’s something that other kids want to be a part of, and that’s been cool to see.”

County News

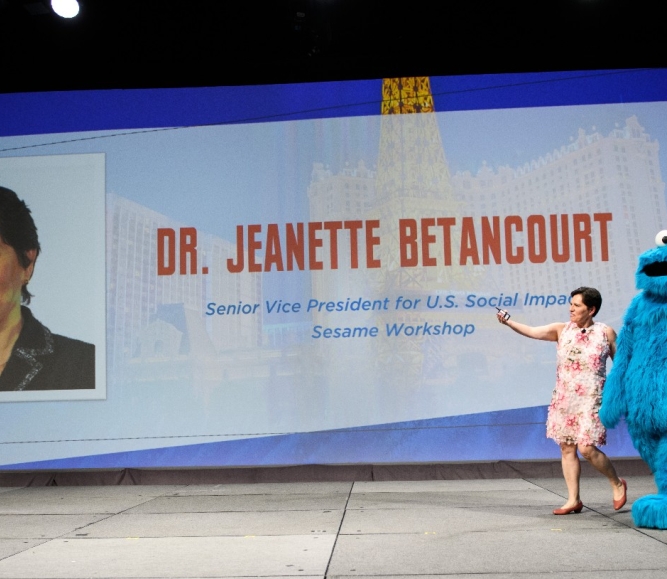

Sesame Street partnership prioritizes youth

Related News

Insights from county leaders on the future of early childhood care and education

NACo's Prenatal-to-Three breakfast and listening session gathered county leaders to identify barriers, explore solutions and support local leaders advancing their priorities.

Team approach, website help California county tackle homelessness

Riverside County, Calif. created a multidisciplinary team to better and more efficiently serve its unsheltered population and share success stories and data through a website.

Ohio county boosts community youth programs with ARPA funding

Hamilton County, Ohio invested ARPA dollars in community organizations through the INSPIRE Youth initiative.