El Paso County, Texas helps migrants on their way

Key Takeaways

The flow of asylum seekers into El Paso County, Texas crosses the Rio Grande River. And like the Rio Grande, the river remains, but the single drops of water are gone before you know it.

Thousands of migrants pass through the county every week, but few stay for more than a day. They move on toward their next destination after buying bus or plane tickets to meet family and friends elsewhere in the United States or boarding buses chartered by Texas Gov. Greg Abbott to take them to New York City, Chicago or Denver.

Learn more

“Almost 100% of them do not plan to stay in El Paso even though we would love to have them, in my opinion,” said El Paso County Commissioner David Stout, who serves as chair of NACo’s Immigration Reform Task Force. “Developers and other business owners ask how we can keep them in town, because they have a need,” for workers.

In fact, they’re mostly gone within a day of being released from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s processing facility, despite 1,200 beds among 25 service providers with whom the county coordinates.

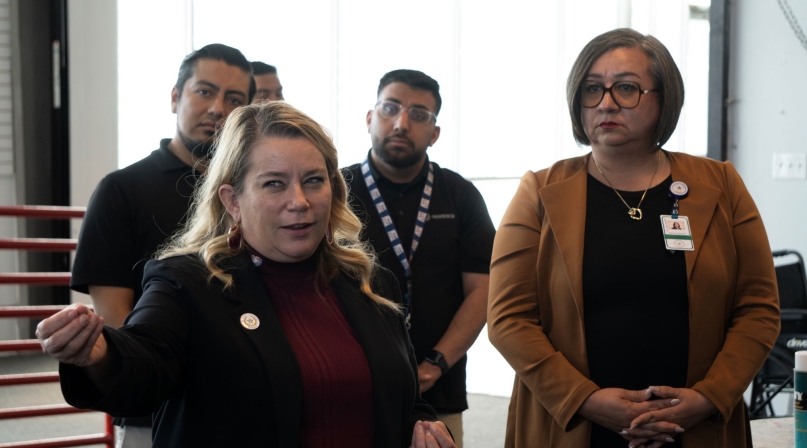

“They want to get away from the border, they want to get to wherever their family is,” said Betsy Keller, the county’s chief administrator, during an Immigration Task Force visit last month to the facility. “They very rarely stay more than a day.”

The county, on the southern border with Mexico on the state’s western end, has long been a conduit for travelers, and the county had a strong network of nonprofit organizations, but 2018 and 2019 were too much even for them, when a surge of migrants caught them by surprise. Stout said that surge galvanized support for the creation of the county’s Office for New Americans.

“We felt like there should have been more of a government response from that point,” said Irene Gutierrez, executive director of the county’s Community Services Department, also during the task force tour.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection thought so too, and approached the county in 2021 to receive asylum seekers when NGOs were once again overwhelmed. Inspired by operations at a Brownsville, Texas day center, El Paso County opened its Migrant Support Service Center in 2022, which then moved into its current 17,000 square-foot facility in 2023. The center focused on serving single adults, allowing NGOs to focus on families, for which they are better equipped.

Migrants are dropped off by Customs and Border Protection after processing at a nondescript building, where they’re met by contractors serving as de facto travel agents, who help them plan their next steps with more nuance and intention than the governor’s mass transit to particular cities.

The center’s goal is to get migrants en route to their families and friends in other parts of the country within the same day to avoid bogging down local shelters. They pay for their own travel.

“It’s much easier to work with their families to get one person out and reunited with their family, to their destination, versus having family units and working with them,” Gutierrez said. “We work with them, their sponsor, family friends …we even contact their country of origin to try to find resources for them so we can reunite them quickly with their families across the country.”

The center serves roughly 600 migrants a day, with capacity for surges of up to 800, and is operated by a Virginia-based contractor, the Providencia Group.

The center’s $1 million monthly budget is reimbursed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Shelter and Services Program. The program took a $150 million hit in the negotiations to fund the federal government through September, putting county-provided services like El Paso County’s, at risk of budget cuts.

Keller noted that the center’s initial growing pains illustrated why its operations were so critical.

“For a couple days before we got in alignment with DHS, we had individuals released on the street,” she said, noting the challenges inherent in traveling in a country where another language is dominant. Without the center, “They’re released on our streets, they don’t know what the airlines are or who to call or how much money they’re going to need, so they kind of sat there until resources were surged in to get them off the streets.”

The center helps make travel more economical by chartering buses to airports with more frequent, varied and affordable flights than the El Paso International Airport offers.

The center’s efficiency helps not just the migrants and El Paso County, but the migrants’ next destination.

“What kind of shape are they going to show up to you in? If they sat on our streets for seven days and maybe not had food or they’ve been subject to a vulnerable situation, they’re going to end up in your communities a lot worse than if we get them through here timely and humanely and safely and with dignity,” Keller said.

She chided the news media for misrepresenting the conditions in which migrants live during their brief stays in El Paso, particularly when using footage from the days before the migrant support services center was opened.

“Some of that footage is sometimes resurfacing and here we are, two years later, people are still using old footage and it gives a bad image for what’s happening,” she said.

Stout added, later, that visits from groups like the NACo Immigration Task Force are crucial for county officials to see for themselves what processes are in place.

“You’ll see in the news a lot of images that try to convince people that there’s chaos on the border and that’s just not the case. That’s why I wanted to have as many people as I can come down here and see firsthand,” through the task force’s visit, he said.

Although El Paso is effectively a way station that necessitates action and administration on the county’s part, Stout remains empathetic to their experiences.

“I guarantee most of these folks probably would rather stay in their country than have to subject themselves to so many dangers, traveling thousands of miles to the United States to only be pushed into the shadows and considered criminals and demonized by folks here whose families did some similar types of movements in the past themselves,” he said.

Despite migrants’ brief stays in El Paso, Stout thinks the region will persist and grow in the national consciousness.

“As our demographics trend more Hispanic, this part of the country will become more important for people as they trace their heritage,” he said.

“Many of them have come through El Paso and instead of looking to Ellis Island, for those of us who have family members that came from Europe, so much more of the population is going to be looking to the southern border and especially cities like El Paso.

That’s the area where so many people’s grandparents or great-grandparents these days first set foot in the United States and we’re the first place where they spent their first night.”

Related News

Insights from county leaders on the future of early childhood care and education

NACo's Prenatal-to-Three breakfast and listening session gathered county leaders to identify barriers, explore solutions and support local leaders advancing their priorities.

Ohio county boosts community youth programs with ARPA funding

Hamilton County, Ohio invested ARPA dollars in community organizations through the INSPIRE Youth initiative.

Team approach, website help California county tackle homelessness

Riverside County, Calif. created a multidisciplinary team to better and more efficiently serve its unsheltered population and share success stories and data through a website.

County News

County leaders seek greater coordination on migrants after border visit

A trip to the southern border in El Paso County, Texas offered county officials a chance to see how the asylum system works, amid a sustained increase in people surrendering to immigration authorities.