Coal counties search for a crystal ball to their futures

Key Takeaways

The transition from coal-dependent economies seems simple — find your next-best resource and capitalize on it.

As eight communities demonstrated through the Building Resilient Economies in Coal Communities Initiative’s capstone, its easier said than done. Maybe there’s no capital to finance such a change. Perhaps building the infrastructure is too daunting. The best hope for survival won’t support the workforce. And sometimes the people who lived that old life aren’t ready, and not just in terms of their skills.

Even as the teams met in Washington, D.C. Feb. 9 to tell their stories and compare notes for an audience of their peers and development professionals, the pair from San Juan County, N.M. would be coming home to a community that saw one of its coal-fired power plants demolished while they were gone. But they were not deterred.

Sasha Nelson, a business owner in Routt County, Colo. noted that transition from a coal-reliant community is a cultural transformation. She’s a member of the Northwest Colorado Development Council, which also included Moffat and Rio Blanco counties.

“I think if it were just an economic transformation, it’d be an easy puzzle to figure out but it’s not,” she said. “It’s very rooted in emotions, and that means people are angry, they’re in denial, they are hard to help.”

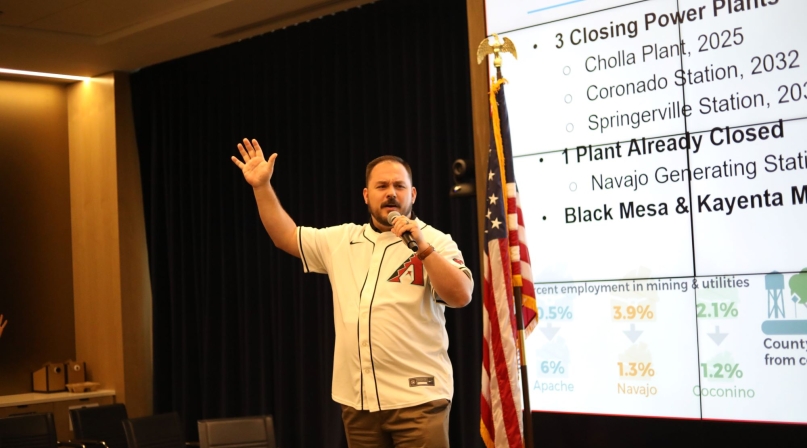

Corey Ringenberg, special initiatives director for Coconino County, Ariz., said a region has to be patient and encourage many different prospective businesses and industries. Investing in what is already there will pay dividends. His county has partnered with neighboring Cochise and Apache counties.

Perry County, Ohio is bedeviled by a brain drain, when young people leave for college and don’t return. The county’s strategy for retaining them includes trying to engage the public in its planned “opportunity center,” being built on the county’s poor farm, which will include community college courses.

“One of the challenges we see with workforce development is that you have to get people to understand and not be afraid and to feel like they belong to the new economy,” said David Hansen, director of Perry County, Ohio’s Community Improvement Corporation. “Not only that, if you want to get people engaged, you can’t simply say to many of them just come and start sitting in the classroom and take it to your degree. That’s not how it works.

“Come work on the farm, come help us with the community agriculture program. So that’s our ramp-up in terms of workforce development.”

Another Appalachian community, Floyd County, Ky., is aiming to build 250 homes within the next five years, both to encourage new residents and also to relocate community members to leave floodplains.

Pike County, Ind. is seeing how a labor-heavy industry like coal extraction is hard to replace, particularly when renewable energy is heavy on setup labor but needs a relatively small workforce to maintain. The county’s coworking facility is allowing entrepreneurs to defray the facility costs that can dissuade them from starting businesses.

“This really launched the ecosystem,” said Bridget Butcher-Mahoney. “This provided entrepreneurs and small business owners a physical place where they could connect, collaborate, engage and find those funding resources they need to take those dreams and those passions and really turn that Main Street business into reality.”

Several teams are leaning in to combatting population drain by setting themselves up as destinations for remote workers, stressing reliable broadband internet and their higher qualities of life.

“What we’re seeing is you can kind of pick where you want to be, where you want to live, where you want to work,” said Amy Baker, one of the Richwood, W.Va. team members. “Because of the remote worker possibilities, we’re seeing a lot of people come back.

Her teammate Cecil Ybanez opened an art gallery in their Nicholas County town, in hopes of attracting the kind of people who can change their town’s fortunes.

“I see arts as being a shiny object, and it’s one way to attract attention to the town,” he said. “We’d like to use the arts as a way to bring creative minds to Richwood, [where] people with a vision can reimagine the future along with us.”

The fact that so many of the communities in the BRECC Action Challenge were several-county entities illustrated the regional approach coal communities must take to survive. They mostly didn’t live their coal days insulated from the rest of the world, nor will they in the future.

“These three counties in the past had been in open competition, but as we face the closing of power plants and coal mines, we realized we were all in the same leaky rowboat together,” said Colorado’s Timothy Redmond, a Routt County commissioner. “So, let’s pull together, work together regionally, not duplicate our efforts and advance the region as a whole.”

Like any large project, an outsized effort goes into breaking out of inertia, and Richwood, W.Va’s Amy Baker looks forward to those efforts paying off, as success breeds more success.

“We want these to be a model for sustainability and something that will spur and catalyze additional development,” she said.

“We really feel like these are going to be the big dominoes, that once they start falling, everything’s going to just continue with that momentum.”

Webinar

BRECC National Network: Shaping your Coal Community’s Approach to Economic Diversification

This webinar outlined a Place Value framework for creating more diverse and resilient economies. Community Builders shared how their work in the West supports developing a unique and localized economic toolbox for communities facing coal transition.

Related News

North Carolina county shell building program draws new businesses

Nash County, N.C. invites potential new businesses to see themselves and their operations in large shell buildings the county erects in its business parks.

Large, small counties grapple with growth

New census data shows that nearly two-thirds of U.S. counties experienced population growth last year, with large counties accounting for most of the growth.