Peer groups, separate dorms power Ky. jail’s substance abuse program

Kenton County substance abuse program tackles inmate addiction from psychological, social, medical fronts

With heroin moving deeper into Northern Kentucky, landing in the Kenton County Detention Center could be as much of an opportunity as it is a punishment for addicts.

Dedicated substance abuse treatment dorms for men and women just celebrated their first year of operation, and the staff is using momentum from its successful three-tiered approach to treatment to continue to help keep inmates healthy after their release. A combination of biological, psychological and social approaches are helping dozens of ready and willing inmates break their addictions.

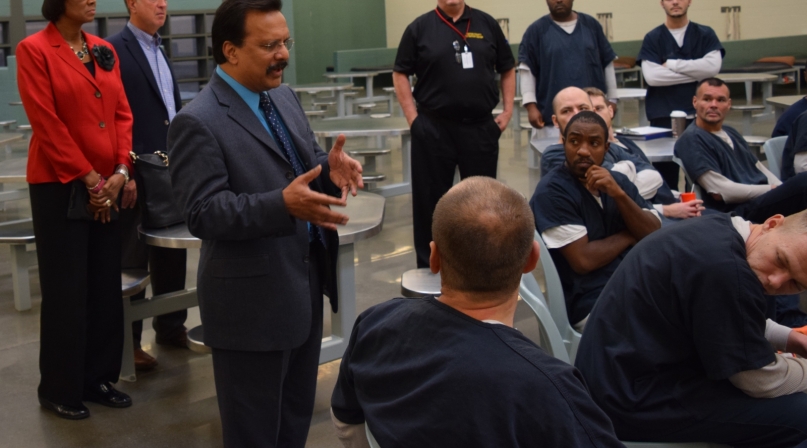

Members of the NACo-NLC Opioid Task Force toured that facility Aug. 19, viewing the programming as a model for rehabilitation. It’s the first medication-assisted treatment program in Kenucky; 14 other county jails have followed suit.

“We have a captive audience,” said Jason Merrick, the director of inmate addiction services. “They have plenty of time and now they have the resources to stand a good chance of success when they get out.”

Programming began in September 2015, funded by the detention center and drawing a few part-time staffers along with Merrick. By Feb. 1, 2016, the jail received state funding — a $9 per diem for each of the 107 inmates in the program, enough to fund operations and support three full-time positions, four part-timers and supplies.

Inmates take a questionnaire as part of the intake screening process, with several questions designed to look beyond just the charges to see why they’ve wound up in jail.

“They might be in on an assault charge or a robbery charge, and that wouldn’t be a big red flag, but when you dig deeper and ask if that was directly or indirectly related to alcohol or substance abuse and they volunteer it, it’s a start for them taking advantage of what we have to offer.”

There is room for 70 men and 37 women in the program, each gender getting an entire dorm.

“Having that kind of space is crucial,” Merrick said. “It sets the participants apart from the general population, helps build communities and keeps them focused.”

The psychological aspect of the program involves a six-month process following an evidence-based cognitive behavioral therapy. It includes socialization, relapse prevention, drug and alcohol education, and breaking down criminal and addictive thinking. In the fifth month, inmates start transitioning towards life outside, with release and reintegration preparation.

The sixth month bleeds into the socialization component of the program, with resume building, budget planning and plans of action for setting the right tone for post-release life. That includes establishing links to service providers outside of the jail.

“I’ve driven some of them over to treatment facilities so they know exactly where they need to go,” Merrick said.

Throughout the program, all participants take part in peer group therapy.

“It’s a chance to get to the root causes of why people act the way they do,” Merrick said. “When they talk about their problems, their peers are asking questions to dig a little deeper.”

Merrick offered an example of the kind of perspective peer therapy lends:

“Say something in their home life is out of their control. They might try too hard to fix and manage those situations, and that’s making things difficult. And their peers can offer suggestions on how to improve those conditions and deal with those stresses. It’s a change from ‘what’s going on out there’ and more ‘what’s going on in here.’”

Asked by a task force member what makes the program work, one male inmate said, “Our fellowship from one addict to another.

“It’s our goodwill and our spiritual growth and the willingness to come to a program (like this) and ask for help.”

Mike Greenwell, one of the jail’s clinical navigators, said the programming bridges a gap for inmates between the world they know and one they aspire to reach.

“Education only goes so far, but you have to teach them there is a world of recovery,” he said. “This allows criminals to break the chains of crime because they’re addicted. They learn how recovery happens, long term.”

As inmates prepare for their release, they are given shots of naltrexone, which reverses the effects of opioid drugs and reduces dependence, giving inmates a pharmacological advantage against the temptation to relapse for the first few months. A pharmaceutical company supplied several dozen free doses to help the Kenton County program get off the ground and now offers the medicine at the Medicaid rate.

“The state prison system gives them a dose earlier on and then another when they are about to leave, but we’re stretching our resources a little more,” Merrick said. “We don’t give them a maintenance shot, but we do test them out and see how they react to the drug.”

And it appears to be working. Through June 1, with more than 200 people leaving the jail having successfully completed the program, only 17 had returned to the Kenton County Detention Center on drug charges, though other county jails’ statistics were not available. When figuring just the inmates who were given naltrexone, the success rate reaches 94 percent, Merrick said.

Greenwell said it all combines, along with the collective effort, to set inmates up for success when they are released. Individually they might not have the same motivation, but the program’s accountability makes a difference.

“They learn to care for each other and invest in their successes as a group,” he said. “These guys have really shown a lot of respect for little things in this dorm like making their beds, staying neat, learning how not to break the rules.

“Different small things that eventually transition into big things.”

Attachments

Related News

Information-sharing bill could protect court workers

The Countering Threats and Attacks on Our Judges Act could provide more than 30,000 state and local judges with access to security assessments, best practices and a database of threats made against colleagues in the justice field.

After historic winter storms, counties assess response

Counties in states that rarely receive much winter weather are assessing their responses to the January storm that left many covered in snow and ice.

California counties fight agricultural crime

Sheriffs' offices and prosecutors in California's central valley make specific efforts to prevent and prosecute crimes against the agricultural community.