Overcoming vaccine hesitancy requires two-way communication

Key Takeaways

The United States will be able to vaccinate 300 million Americans after the federal government acquired an additional 200 million additional doses, President Biden announced Feb. 11.

Meeting that goal will require those people to accept the vaccine, but distrust of new medical procedures along cultural and racial lines can be a roadblock to an efficient road to full vaccination and herd immunity.

“The honest truth is that we have to have difficult conversations with folks, we have to engage them,” said Dr. Raynard Washington, deputy director of the Mecklenburg County, N.C. Health Department. “We can’t meet resistance from one person and then just move on to someone else, we have to get everyone.”

Learn More

The most important approach, Washington said, will be to not force vaccination on anybody or make them feel bad about not trusting a vaccine, but having responsive conversations that give public health practitioners a chance to inform.

“One of the most effective ways has been documenting and telling stories,” Washington said. “The most effective ways to get people over the hump of hesitancy is to share other people’s experiences: Why they were hesitant, why they decided to get the vaccine, what the experience looked like for them.”

“People are able to identify with experiences.”

It was people’s experiences and the legacy of those experiences that have put public health at a disadvantage with minority communities, the decades-long Tuskegee Study casting the longest shadow.

“Patients and communities have a right to distrust health communities, health officials,” Aletha Maybank said on a recent American Medical Association webinar. She is the AMA’s chief health equity officer.

“It is a really rational place for them to come from, especially for Black and brown communities. There are well-documented harms, both in stories that have been passed across generations and the lived experience. And there’s growing scientific evidence that tells us our systems and culture of health and medicine are impacted by racism.”

Health systems are attempting to apply equity to vaccine distribution, particularly as minority communities take the brunt of the impact of COVID-19, with African Americans dying at nearly twice the rate of white patients and hospitalized at nearly three times the rate of whites, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, despite experiencing only a slight increase in community spread.

Most counties are still trying to reach older populations, and Washington said the ethnic breakdown among older Americans has delayed real-time feedback about how much vaccine hesitancy exists across demographics.

“African American longevity has played a part; we don’t have many 75-plus-year-olds as other ethnic groups,” he said. “We’ll start to see this play out as we move into vaccinating different segments of the population.”

Mecklenburg County’s approach to addressing hesitancy starts with providing accurate and timely information about the vaccine, specifically around safety and its effectiveness. Because the county is home to a large immigrant population, its materials are available in 12 languages besides English.

“We want to deliver that information to folks in a way that’s understandable and culturally competent, culturally appropriate,” Washington said. “We’re partnering with our health care system, so we have a united front [on messaging] and we’re not saying different things.”

Washington said the county’s health department maintains relationships with various organizations that represent racial and ethnic minorities, and that “tree of dissemination” has been an effective way to reach people’s trusted messengers —whether it’s a member of the clergy, a social service provider or community group leader.

“We have to make sure the sources that people regularly hear from and trust have the right information about the vaccine that they can disseminate,” Washington said. “We want to reach anyone who has an audience, so we’re working with faith groups, fraternities, sororities and business leaders.”

Employees of the health department reach out to their own families and social groups to get the word out, serving as unofficial spokespeople in their networks.

“We always tell people that they’re some of the best messengers we have,” Washington said.

The county is using a traditional media campaign, with television, radio, print, digital and social media advertising, but also billboards in targeted neighborhoods. To limit personal interaction, outreach workers are distributing informational doorknob hangers.

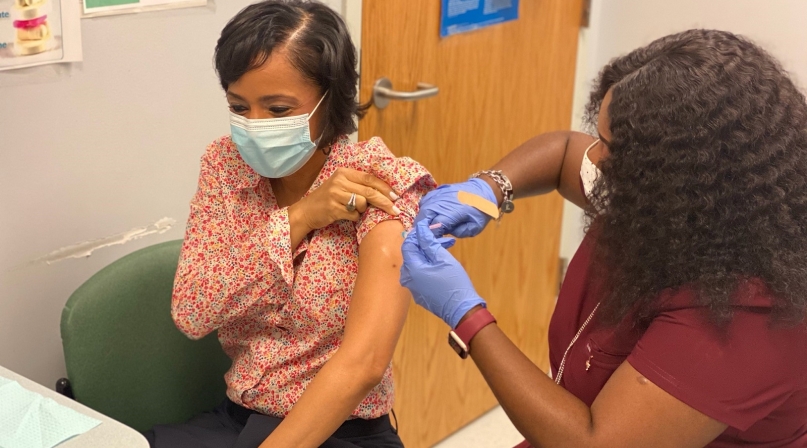

County and civic leaders have tried to spread the word about their own trust in the vaccine — Washington documented his own vaccination — but testimonials from regular people, spending time to explain what motivated them to trust the vaccine, goes a long way.

So too does a realistic approach. The county is upfront that some patients have reported soreness the day following their second dose and acknowledges that some people will feel that.

“We were intentional, we included in our messaging at the top, about the second shot side effects,” Washington said. “We don’t want people to have the reactions and think this is abnormal. We didn’t want to be unrealistic.”

And the flow of information has to go both ways, and health department workers need to be sensitive to people’s concerns and figure them into further efforts.

“You can’t overcome hesitancy if you don’t understand why they’re hesitant,” Washington said. “We can learn from them as much as they learn from us. We’re constantly learning.”

While counties can plan robust campaigns to increase confidence in the vaccine, the supply chain is working in their favor as they refine their messaging and take the time they need to get people on board.

“Not everyone will be ready to go from day one, and in some cases it’s OK we don’t have enough vaccines yet, because with some people, it does take time,” Washington said.

Attachments

Related News

Drug tracking software helps counties identify trends, save lives

Florida counties are using an artificial intelligence tool called Drug TRAC to track and report drug trends, with the aim of providing quicker outreach and saving lives.

White House Executive Order establishes national substance use disorder response

On January 29, the White House issued an Executive Order (EO) establishing the Great American Recovery Initiative, a new federal effort aimed at coordinating a national response to substance use disorder (SUD).

USDA and HHS release new dietary guidelines

On January 7, U.S. Department of Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. unveiled the new Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2025–2030.