Helping children left behind by trauma

Author

Upcoming Events

Related News

Key Takeaways

The father of four died from a drug overdose, so the story from Leslie Horton went. His oldest child found him when she returned home from school, followed — one by one — by the next three children, as they also returned from school.

The situation they encountered is a straightforward example of what developmental experts call an adverse childhood event, the type of trauma that, down the line, can lead to a host of problem behaviors in school, suicide or quite possibly drug addiction or incarceration later in life as well, said Horton, who heads the Yavapai County, Ariz. Community Health Services public health agency.

Learn More

Yavapai County’s Trauma Lens Care program, or TLC, seeks to sidestep the cycle of failure and anti-social behavior before it even begins, Horton said, by intervening in the child’s life with counseling and other social services as soon as possible.

It’s a simple, yet elegant concept: Local law enforcement notifies the TLC program — usually by email, but sometimes by phone — when a child is at the scene of a law enforcement intervention such as a drug bust or a violent crime. Officers provide TLC with the child’s name, age, a brief description of what happened and the name of the school the child attends. In turn, TLC staff provides the school or daycare center with a heads-up.

“We actually bridge that information to the school,” she said. In most cases, the schools have counselors who can immediately intervene. If not, they have people that will periodically check in on the child.

What they found before was that schools combed newspapers and crime reports for news about children’s parents, whether they had been arrested or had died from a drug overdose, Horton explained.

The information, however, might have taken a while to circulate to the school. In the meantime, “the child may be struggling. They might have been disciplined because the teacher doesn’t know what went on,” Horton said, “and a lot of times, the kids won’t say. The TLC program hopefully gets the kids resources right away and a little extra attention in the classroom, too.”

Although only a few months old, TLC has enjoyed an overwhelmingly positive response, Horton said. One recent two-day period saw six reports forwarded from the police, she said. “Law enforcement wants to know if something happens to the kid.”

Connections formed 15 years ago at the height of the meth epidemic among dozens of social service agencies throughout the county, as well as law enforcement and school systems, provide the backbone of the program.

“Within Yavapai County, we have this huge network of partner agencies we can all upon,” she said.

The network came in handy when public health nurses conducting parenting classes in the county jail heard stories from inmate parents about the children they left behind: the kids who were having to deal with the aftermath of their parent’s illegal activity.

It was one of those nurses, Stacey Gagnon, Horton said, who got the program going.

On the school side, Yavapai County’s public health officials offer trauma-informed training for teachers to help them recognize the behavioral indications of trauma and how they can help students develop a greater sense of safety at school.

The program is not unusual, Horton said. There are similar programs across the country, “probably back East where you are. What we’ve done is tweak it and tailor it for our community. And it keeps changing as we learn new things, like we can’t work with EMS because of HIPPA regulations.”

Horton is on something of a crusade about TLC. She made a presentation recently at a National Governors Association meeting, which sparked some interest, and maybe, she hopes some funding, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“We’re looking for ways to not only build the program but to expand it — to make it a practice other counties can take on.”

Interview with Stacey Gagnon, Yavapai County, Ariz. TLC Program

CN: We understand you began to see the need for a TLC-like program in the course of your work offering parenting classes to inmates of the county jail? Is that correct and could you elaborate a little more?

I wrote about this recently. Here are my reflections.

I taught a class at the jail today and there was this beautiful moment.

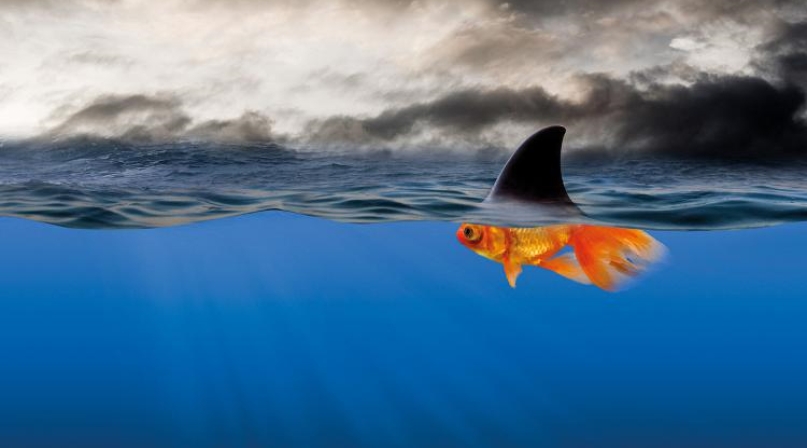

I was sharing the picture below and talking about how our children often present with behaviors that look like the shark, but if we look below the surface, we will realize they are really just scared goldfish trying to have a need met. Their behaviors might communicate anger and hostility, but below the surface is fear and a hurting child.

The shark-like behavior that shows looks to be what we might call “unacceptable” as the child reaches out to try to satisfy unmet needs. It’s our job as parents to stop parenting the shark fin, and look below the surface to parent and meet the needs of the goldfish.

One of the inmates raised her hand and said, “I’m a lot like that picture. I act all tough and mean, but I’m really just a scared fish. I wish when I was a kid, someone would have thought to look for the goldfish, instead of just seeing me as a shark.”

Here is where I saw the absolute need for teachers to see what was happening outside the classroom walls. I started doing some research and found a similar program back East that did something on a much smaller scale. As a former school teacher, I knew the role that I had played in many children’s lives and also how blind I was to the actual trauma many of my students had experienced at home (this is why I called it Trauma Lens Care). There were many times that I would learn weeks or months later about traumatic events and by then I would have responded to the shark fin instead of understanding the goldfish.

CN: What were your first steps in getting the program off the ground?

My first steps were having an amazing boss that lets me run with ideas. I obtained a secure email - tlc@yavapai. us and Leslie started putting me in front of all her contacts. It has spread like wildfire.

CN: How long did it take?

From initial idea to first TLC email was weeks.

CN: What were some initial obstacles?

Schools have been the biggest obstacle. There is fear in such big and scary information. It’s hard to hear about what our children go through because with knowledge comes responsibility to act. Many schools feel ill-equipped to respond.

CN: How did you overcome them?

I am working on trauma-informed classroom trainings for teachers. I have already presented on this topic and it is a complete shift in how you run your classroom. I am a mother of seven, with five adopted children. This dramatic shift in responding to behaviors is what I have had to learn over the past 12 years. It helps that I taught in the public-school system before I went back for my nursing degree. This gives me a bit of leverage because I know how a classroom runs.

CN: How long has the program been operating?

About three months.

CN: What are the next steps?

I am expanding to parenting classes in the community because evidence shows that when we look at ACEs (adverse childhood events), our biggest impact is teaching parents. I am also looking to expand the jail program to continue with familial support and classes once an inmate is released. TLC should be more than just the spread of information. It needs to have the trainings to support the teachers, the officers and parents.

Attachments

Related News

Stretching small opioid settlement allocations helps funding do more

States and localities are set to receive $56 billion in opioid settlement dollars over an 18-year period, but not every county that receives settlement funding will get enough to build out infrastructure.