Crisis in West Virginia’s Coal Counties

Author

Upcoming Events

Related News

NACo provides technical assistance to counties impacted by the coal industry downturn

The collapse of coal usage and prices has created financial crisis for West Virginia coal counties. The 38 percent decline in West Virginia coal production coupled with a 71 percent decline in prices since 2008 has emptied the coffers of counties who have for decades relied on income from coal taxes. The same forces have left state government with its own crisis and unable to aid the counties’ distress.

Learn More

Visit DiversifyEconomies.org

Contact Jack Morgan

Following Wyoming, West Virginia is the nation’s second largest producer of coal. Most of that coal has fed the boilers of electric power plants. From 166 million tons in 2008, production fell to 102 tons in 2015. Projections show a further decline in 2016 to 95 million, which would push the decline to 42 percent. Since 2011, prices for West Virginia coal fell from $139 a ton to $40. Direct employment in the mines has declined by 35 percent.

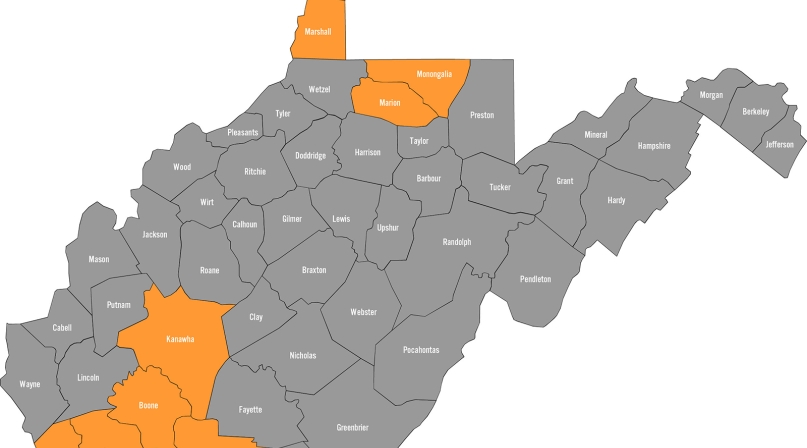

This double disaster for coal has produced devastating effects on coal counties particularly in those counties where coal accounted for over 30 percent of the counties’ total income. Coal is produced in two distinct fields in West Virginia: north and south. A recent study looked at the 10 largest coal producing counties, five in southern and four in the northern region (see map).

The impact among West Virginia coal counties has been uneven with the southern coalfields seeing the greatest declines in production. Boone County, which until a couple of years ago was the state’s largest producer, saw a production decline of 67 percent, Logan 50 percent, and Mingo of almost 40 percent between 2011–2015.

The decline in coal production and prices has significantly reduced the personal income received by those living in the West Virginia southern coal counties with a lesser impact in the north. For Boone County total personal income has fallen to less than 70 percent of its 2011 level in Boone, with Mingo at 67 and Logan at 85 percent of 2011 levels.

Due to state constitutional and statutory provisions, county governments are highly dependent on revenues directly related to coal property and severance taxes. Revenue from real property taxes has fallen in all coal counties by an average of 35 percent with more dramatic declines anticipated. Coal counties are at the maximum rates allowed under the state constitution, so raising revenue by levy increases is not available to them.

As coal production and prices have decreased, so has the severance tax to both the state and the counties. The state levies a 5 percent severance tax on the gross value of coal extracted. This is split with 93 percent going to the state’s general fund and 7 percent distributed to the counties. Of the county share, 75 percent returns to the county government where the coal was produced, and 25 percent is distributed to the all municipalities based on population.

In 2012, a Reallocation Severance Tax was enacted allocating a small portion of the state tax to counties to partially offset the loss in their portion of the severance tax. But a $20 million cap has proved insufficient to replace the lost county revenues.

Exacerbating the situation is the bankruptcy of all the major coal producers. While in bankruptcy, these firms have not paid the property taxes due. Often these amount to millions of collections. As these companies emerge, there may be at least some partial payment of these past-due accounts.

How have the counties responded to these significant reductions in their fiscal capacity? For some, county services have either been eliminated or reduced. Reduction in staffing and cuts in working hours are a result. As positions come vacant they are not being filled. Others have raised fees for service like trash removal. Some have dramatically cut services in volunteer fire departments, for fairs, libraries, parks, animal control or reduced landfill and trash compactor hours.

Other counties have been able to continue funding their programs using reserve funds accumulated during the boom years, but all acknowledge that solution is temporary. One county put special levies on the ballot to support county functions that otherwise would have been eliminated or reduced. Five of the six passed.

In this picture there is one bright spot. Forty percent of West Virginia’s production is metallurgical coal. This coal is the choice for steel manufacturing. As the worldwide recession lessens, demand for “met” coal will increase.

What has not been quantified are all of the indirect effects of the collapse. Residential and commercial property values have declined in most counties as mines have closed and unemployment rises. Retail sales are down. Trucking and the railroads have seen the volume of their traffic reduced leading to elimination of terminals and employees.

West Virginia coal counties, particularly southern ones, are already struggling with unemployment rates and poverty rates well above the national average.

Those counties are being challenged to overcome other issues including: lack of economic diversification, isolation from adequate transportation, little flat land for industrial development, drug-related crime, limited supply of quality housing, absence of amenities and a workforce with low educational achievement. While these problems are being addressed, the solutions are long term.

The decline in property and severance tax revenues makes the solutions more difficult to attain. Unless there are new sources of revenue found for coal-county governments in West Virginia, their capacity to deal with these issues will be constrained.

Attachments

Related News

North Carolina county shell building program draws new businesses

Nash County, N.C. invites potential new businesses to see themselves and their operations in large shell buildings the county erects in its business parks.

Large, small counties grapple with growth

New census data shows that nearly two-thirds of U.S. counties experienced population growth last year, with large counties accounting for most of the growth.