Counties fashion anti-trafficking programs

That first call was the big test.

The Los Angeles County law enforcement agencies and probation department reached an uneasy truce on how to treat minors who have been picked up for prostitution.

“If they (police officer) were sitting with a 14-year-old for six or eight hours, waiting for someone who might not come to pick them up, that’s time they’re not out on the street doing their job. We get that,” said Michelle Guymon, director of the Child Trafficking Unit with the Los Angeles County Probation Department.

At the same time, as a minor, the child could not consent to sex and was the victim of statutory rape and likely other kinds of abuse in “the life” of a trafficking victim. A jail cell was about the worst way to be treated.

So law enforcement agencies and the probation department had a deal. When a detective or police officer somewhere in the county identified a child as being involved in prostitution, a call would go out to the probation department. A caseworker would have 90 minutes to reach the child at a police department or hospital and take custody.

In August 2014 the first call to the hotline came in. The clock was ticking. Getting anywhere fast in Southern California is a challenge, but this was a child’s future on the line.

“The detective from Long Beach had his stopwatch out,” Guymon said. “It took 74 minutes.”

That response — law enforcement told Guymon 90 minutes would never work — built the foundation for a partnership between the two departments which, along with child welfare, comprise the county’s Sex Trafficking Integrated Leadership Team.

It’s just one way counties have developed programming to address the care of human trafficking victims and the demand that threatens to draw more children into “the life” of prostitution.

Demand and enforcement

Men convicted of engaging in prostitution in King County, Wash. are ordered by the court to a 10-week course designed to teach them about the consequences of engaging in sex trafficking. It’s one of the most extensive “John schools.”

“The vast majority (of buyers) are opportunistic and just looking to buy sex,” said Ben Gauen, senior deputy prosecuting attorney for King County. “They don’t think about the chance she could be 15.”

The classes deconstruct why people feel they need to buy sex and hammer home that prostitution isn’t a victimless crime.

“It’s a crime of power and privilege,” Gauen said. “The vast majority of people involved in prostitution do it because they lack viable economic alternatives, they’re used to cycles of abuse. It’s pretty eye-opening.”

Successful completion of the course will keep offenders from incarceration, or at least reduce their sentences.

“We’re not trying to send these people to prison for long periods of time or at all unless they have a (criminal) history, it doesn’t do us any good,” Gauen said. “We know the majority of people are not prosecuted or caught when engaging in this behavior, but those we can reach can go a long way to reducing demand.”

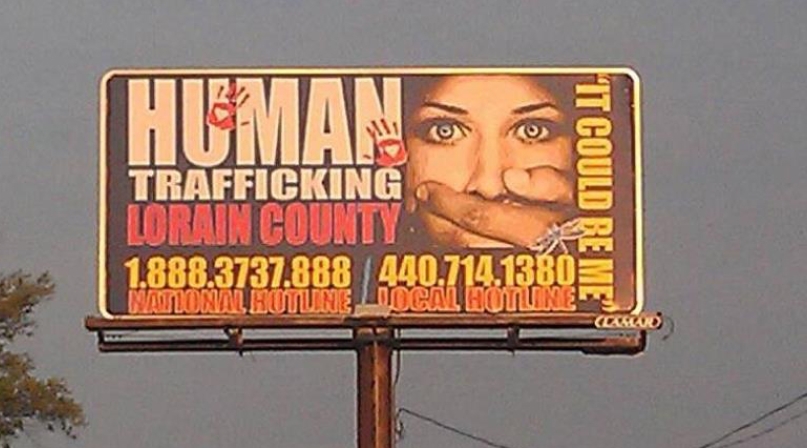

Other counties have approved ordinances to disrupt human trafficking in businesses. Los Angeles County requires motel owners to sign contracts disallowing any form of sex trafficking to take place in their facilities and hang posters in visible places with hotline information to report a possible human trafficking incident and for victims to receive help. They must also allow law enforcement to check guest registries at-will and take a training session on sex trafficking provided by the county. Hillsborough County, Fla. passed an ordinance in August 2018 creating a permitting process for massage parlors and bathhouses, frequent venues for trafficking, which includes an educational process for employees of these establishments.

Treatment for victims

McLennan County, Texas gets high marks from the nonprofit Polaris Project for the county’s prosecutorial methods when making the case against traffickers.

In addition to not charging victims, prosecutors take great pains to build their cases without victims’ testimony.

“They build circumstantial cases against traffickers by following the money and business operations that trafficking supports,” said Rochelle Keyhan, Polaris’ director of disruption strategies. “They gather enough evidence that they don’t have to build their case on the backs of survivors, which could traumatize them to recount it in court.”

The consequences of “the life” don’t end when the slavery does. Davidson County, Tenn. took that into account when developing its trafficking court, Cherished Hearts. If a screening process indicates that women in the judicial system had been involved in trafficking at any point in their lives, it opens the door to social services to address that trauma.

“We put them in stabilized housing, get them clothing, counseling, drug rehab, any resources that will help,” said Sarah Wolfson, assistant district attorney. “It’s a chance to rehabilitate them, because chances are whatever happened to them years ago has contributed to what brought them into the justice system now, even if it happened 10 years ago.”

Once a sexually exploited youth has been identified, assessed and triaged by the Hennepin County Children and Family Services team, the youth will be assigned a social worker who specializes in working with sexually exploited youth. The specialized social worker will work with youth to create a comprehensive, trauma-centered individual service plan that reflects each youth’s strengths and needs. The specialized social worker will incorporate, when applicable, the sexual assault and domestic violence services that Hennepin County already has in place, to ensure a comprehensive service plan.

Hennepin County, Minn.’s “No Wrong Door” also dedicates funding for an investigators and prosecutors to focus on sex trafficking cases.

It’s not just changes in how counties treat victims or perpetrators that make the difference. Hennepin County’s training goes as far down to front-line county employees.

“It’s subtle things like language and word choice,” said Commissioner Marion Greene. “These employees in our health department, sheriff’s office…people who might come in contact with trafficking victims.”

When developing the Los Angeles County Law Enforcement First Responder Protocol, Guymon said it was crucial to be as responsive to victims’ needs as their pimps.

“They’ll tell them, ‘who else is going to pick up the phone when you call in the middle of the night,’ as a way to create dependence and trust,” she said. “That’s why we have to be there, too.”

Many of those children have long histories of being let down by adults, so counties have a chance to break that pattern.

Greene concurred, and that backs the county’s mandate to all county service providers.

“There’s a lot of distrust because these kids likely had bad experiences that involved county social services before,” she said. “We need to communicate as government, ‘We see you.’”

Attachments

Related News

USDA and HHS release new dietary guidelines

On January 7, U.S. Department of Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. unveiled the new Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2025–2030.

County Countdown – Dec. 15, 2025

Every other week, NACo's County Countdown reviews top federal policy advocacy items with an eye towards counties and the intergovernmental partnership.